The developer and the justice on the nation’s highest court cruised the world together for nearly 30 years — a friendship between politics and real estate that rose to a level rarely seen before.

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas didn’t disclose those rides aboard the Bombardier Global 5000 private jet or the 162-foot superyacht. He didn’t disclose the trips to Bohemian Grove, the volcanic archipelago in Indonesia or the private resort in the Adirondacks.

He didn’t pay for them, either.

The tab fell instead to Harlan Crow, a Dallas real estate legend who became the reluctant subject of media scrutiny last month when ProPublica released a report detailing decades of friendship — and all-expenses-paid vacations — between him and Thomas.

After the initial story, there were more reports, more condemnations from political opponents and more questions raised. Crow held a two hour non-apology audience with the Dallas Morning News, defending the friendship and firing back at those who thought it was inappropriate.

So far, any actual fallout has been minimal. Thomas still wears the black cloak, and Crow Holdings is still printing money.

“Simpatico”

Harlan’s father, Trammell Crow, built his eponymous company into one of the largest owners of commercial real estate in the business. In 1984, his empire spanned some 142 million square feet, Texas Monthly reported, but the patriarch had no obvious successor.

Harlan, who in 1988 took over what was then the company’s residential development arm, Crow Holdings, quickly proved himself up to the task. Snatching his family’s fortune out from the teeth of the housing market crash, the younger Crow expanded his realm to include Trammell Crow Residential, Crow Holdings Capital, Crow Holdings Industrial and Crow Holdings Office. Today, the firm manages about $30 billion in assets and ranks among the country’s most active multifamily developers.

We found out we were kind of simpatico.

Crow’s friendship with Thomas began 27 years ago, he told the Dallas Morning News. Both were leaving Washington, D.C., for Texas — Crow to return home from a meeting with executives of a free-market think tank, Thomas to give a speech in Dallas for the same think tank marking his fifth year on the court.

“During that flight, we found out we were kind of simpatico,” Crow told the newspaper. “We come from absolutely polar opposite life stories, but we had a lot in common.”

Thomas was introduced at that speech by another major player in Texas real estate, his longtime friend Alphonso Jackson, then the leader of the Housing Authority of the City of Dallas. In his opening remarks, Thomas thanked Harlan and Kathy Crow, as well as their parents, for “their courtesy and their warmth.”

In his recent sit-down with the Dallas paper, Crow was careful to say he was a moderate Republican supporting moderate causes that didn’t always align with Thomas’ views — not that they discuss them much. Crow said they talk a lot about their kids and dogs.

However, his interest in politics occasionally conflicted with his desire to stay in the background. In the late 2000s, as Dallas considered building a publicly owned hotel near the city’s convention center, Crow contributed almost a million dollars to a campaign aimed at stopping it.

The move thrust Crow, whose firm owns the Hilton Anatole hotel downtown, into a public standoff with high-powered antagonists like then-Mayor Tom Leppert. But Crow refused to participate in a town hall, debate or interview about the project, leaving questions to Anne Raymond, then a managing director with Crow Holdings.

“I’m willing to debate Crow anytime,” Leppert told the Dallas Morning News in 2009. The mayor didn’t get his wish for a public confrontation, but Crow didn’t have his druthers, either: The hotel was built in 2011.

The secret sale

ProPublica released its findings in two reports. The first, simply titled “Clarence Thomas and the Billionaire,” dropped before dawn on April 6.

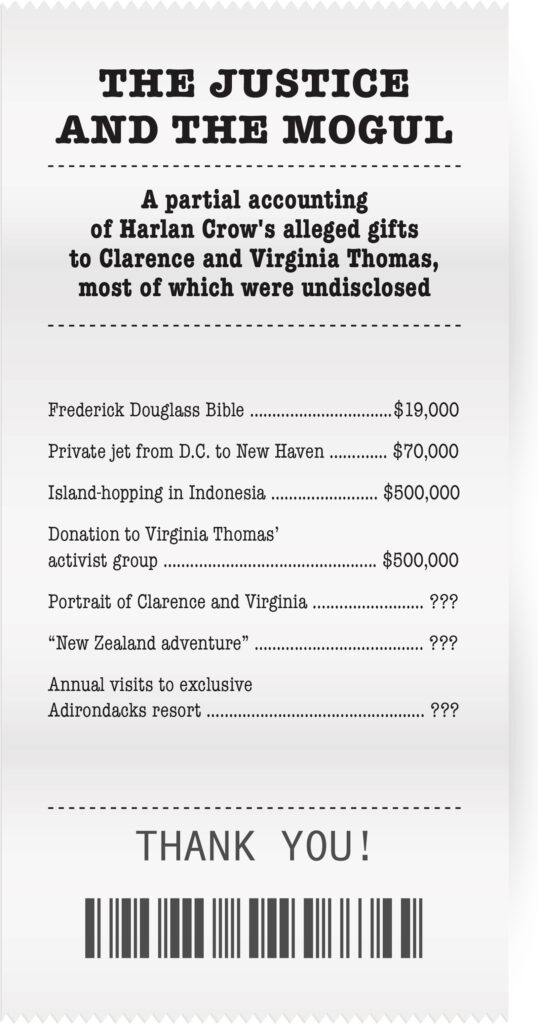

The piece makes several direct connections between Crow and Thomas. It says Thomas flew on Crow’s jet to go island-hopping in Indonesia on Crow’s yacht, the Michaela Rose. The publication calculated that the trip could have cost more than $500,000 if Thomas chartered it himself.

Thomas also spent a week almost every summer at Crow’s Adirondack resort, Camp Topridge. As a rule, Crow’s guests at Topridge never pay to stay there.

Not every trip was an extravagant getaway — the report found that Thomas had even used Crow’s plane for a same-day trip between Washington, D.C., and New Haven, which as a charter could have cost around $70,000.

The main hangup of the revelations was that, despite accepting an untold sum of gifts, Thomas almost never listed them on annual financial disclosure forms.

The gifts from him and his wife to Thomas were “no different from the hospitality we have extended to our many other dear friends,” Crow said in the article. But ethics experts were not so sure.

“It’s incomprehensible to me that someone would do this,” Nancy Gertner, a retired federal judge, told ProPublica.

The story also detailed Crow’s wider political connections, listing a string of conservative think tanks and policy centers to which he has donated. It tabulated more than $10 million in political contributions, not counting “dark money” groups. Politico reported that Crow had anonymously donated $500,000 to fund Liberty Central, a nonprofit political advocacy group founded by Thomas’ wife, Virginia.

In a later interview, Crow disputed the idea that he is a political puppet master. “I have been a donor to moderate Republican individuals running for office, as well as groups that are involved in that kind of world to support more moderate Republican stuff.” He estimated that he has donated in the “low number of millions” over the past five years.

ProPublica said it uncovered the details of its story by combing through internal documents and flight records, as well as interviewing dozens of witnesses to the relationship ranging from yacht staffers to Bohemian Club members.

Crow called the ProPublica report a “political hit job” and asserted that the organization is on a mission to destabilize the Supreme Court.

“If Harlan Crow disputes the accuracy of our reporting involving Justice Clarence Thomas, we invite him to provide us with the details so we can correct any inaccuracies,” said Stephen Engelberg, editor-in-chief of ProPublica.

Less than a week later, ProPublica followed up with a second story, even more tied up with real estate than the first one. In 2014, Crow purchased a Savannah, Georgia, home from Thomas in which the justice’s mother lived. Thomas did not disclose the $133,363 sale in his annual financial report, an omission around which there seemed to be less ethical ambiguity than the trips: Federal disclosure law requires justices to report most real estate sales worth more than $1,000.

It’s incomprehensible to me that someone would do this.

Crow, a prolific collector of historical artifacts, said he planned to turn the home into a public museum. Fittingly, he bought the house through an entity called Savannah Historic Developments LLC. He later told the Dallas Morning News that he thought Thomas’ mother owned the house.

The Washington Post later reported that Thomas has disclosed income from a family real estate business, “Ginger Ltd., Partnership,” although the company technically folded and was replaced by another entity, Ginger Holdings. That report, which may have revealed nothing more than a clerical error, hasn’t had the same juice as ProPublica’s findings.

Until recently, Thomas has defended his lack of transparency around the gifts from Crow in part by saying Crow’s businesses didn’t have any cases before the court. But even that claim has come under review, as Bloomberg reported that in 2005, the Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal from an architecture company seeking $25 million from Trammell Crow Residential. While Crow Holdings didn’t own the business, it held a non-controlling stake in it, making the case the closest thing yet to a direct conflict resulting from Crow and Thomas’ friendship.

Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden asked Crow last month to provide a detailed list of the gifts he has given Thomas, calling the relationship “unprecedented” and saying that “the secrecy surrounding your dealings with Justice Thomas is simply unacceptable.”

Crow himself has largely stepped away from the business in recent years, plugging in Morgan Stanley veteran Michael Levy as CEO. In the midst of the news stories, Crow Holdings is still doing deals, most recently filing plans to build a $38 million logistics center in Dallas.

Though much remains the same, the justice and the developer’s summer plans might be a little trickier to pull off this year.