Buyers seeking warm weather and the amenities of oceanfront living have often sought out more affordable units in older buildings along South Florida’s waterfront. But now the supply of those condos may be dwindling.

Buyers seeking warm weather and the amenities of oceanfront living have often sought out more affordable units in older buildings along South Florida’s waterfront. But now the supply of those condos may be dwindling.

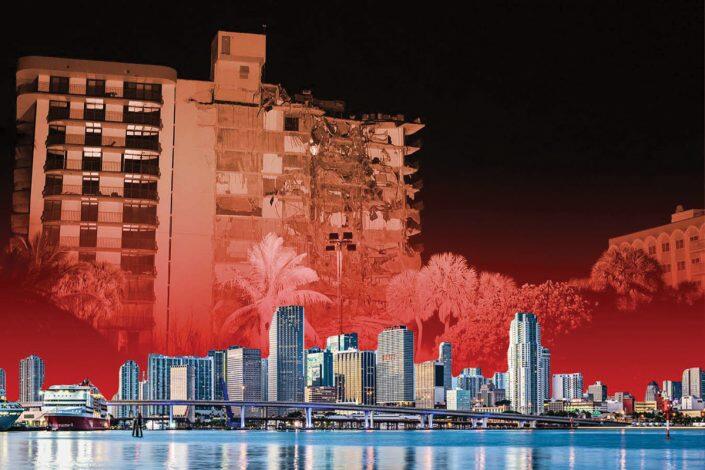

Developers, facing little to no inventory of undeveloped waterfront land, are increasingly targeting bulk buyouts of these buildings. And unit owners are more likely to embrace those offers, especially in the wake of the Surfside collapse of Champlain Towers South that killed nearly 100 people.

Although an official cause of the collapse has not been identified, unit owners and the condo association were aware of critical structural problems, including leaks in the pool deck and cracks in the concrete. The building had just begun $15 million in major repairs required to receive its 40-year recertification.

The collapse triggered Miami-Dade County, various cities and individual buildings to order inspections of older buildings, prompting condo associations to deal with issues they may have previously ignored or delayed indefinitely. If they don’t, their building may be declared unsafe and ordered evacuated, with residents unable to return until properties are brought up to code.

But not all unit owners can afford the often costly repairs. Enter developers who can offer bulk buyouts above market value. Since the collapse, investors have been identifying buildings to bid on, and industry experts predict deals will surge once more structural and engineering reports come in.

The price a developer is willing to pay is determined by the project that can be built on the site. Still, the more divided unit owners are, the less likely they are to come to an agreement. And while developers will likely offer more to a unit owner than an individual buyer might, it may not be enough for the seller to afford a similarly located and sized condo, especially in today’s market.

However, the unit owners also are unlikely to be able to afford repairs if they want to stay.

“We’re not talking about putting film on windows. We’re talking about foundations and rebar. It’s going to be very expensive,” said Bilzin Sumberg attorney Martin Schwartz. “You can tell people they have to be in a safe building, but where are they going to get the money from?”

Florida law requires more than 95 percent of unit owners to agree to terminate a condo association, which can be a challenge for bulk investors looking to redevelop a property.

“You’re not dealing with one seller. You’re dealing with multiple sellers,” said Taylor Collins, a principal at Two Roads Development, which just completed its first bulk buyout. “It’s a very emotional process. A lot of times, people realize the building is at the end of its life.”

Recent deals

Two Roads brought in the Related Group as a joint-venture partner to acquire Carlton Terrace, an oceanfront condo building in Bal Harbour. They paid about $130 million for the 88-unit building this summer. But the partners were not the first developers to attempt the deal. Carlton Terrace had been on the receiving end of roughly 10 offers over the years, sources say.

To find these deals, developers are tracking the market. Two Roads has a map of buildings that are 30, 35 and 40 years or older on the water in Miami-Dade and Broward counties, with a zoning map overlaid to determine what can be built on the property, as well as the price it is willing to pay unit owners to acquire the building.

“Sometimes, if we really like a building and think it’s going to come to market in three to five years, we’ll start buying units today,” Collins said.

Mast Capital, a Miami firm led by Camilo Miguel Jr., paid more than $100 million to acquire La Costa, a 124-unit oceanfront building in Miami Beach starting in May, with plans for a luxury condo tower on the site. After the June collapse in Surfside, the La Costa building was declared unsafe by Miami Beach and was ordered evacuated.

Following the collapse, developers may have an easier time convincing unit owners to sell, experts say.

“The sales pitch is enhanced, unfortunately, by the safety factor,” said attorney Bill Kramer of Brinkley Morgan. “If you’re living in a $200,000 condo and it’s going to cost $100,000 in repairs, could you possibly afford it? It kind of doesn’t make sense.”

Insufficient reserves

Multimillion-dollar estimates for major repairs don’t come out of thin air. Condo associations, under pressure to keep monthly fees low, will often defer maintenance and postpone projects. Florida law allows associations to waive funding reserves for projects greater than $10,0000 by a simple majority.

“That’s why you hear of huge special assessments to fix the things they knew they would have to do,” Kramer said.

He and others expect the law regarding reserves will eventually change. Since the Surfside collapse, a number of buildings have hired firms to complete reserve studies.

“The reality is there has never been a total regulation of these buildings to actually make the repairs. It’s very likely that as associations are being forced to make repairs, they are not going to be able to,” said attorney Keith Poliakoff of the Fort Lauderdale-based Government Law Group.

Oceanfront properties, especially, are on the receiving end of “tremendous wear and tear,” Schwartz said. And many of the owners in older buildings have fixed incomes.

Divided house

David Cohen, an executive at the property management firm AKAM, said that the challenging part of a buyout is still getting enough unit owners on board, calling it a “public relations battle.”

Longtime Related executive Carlos Rosso, who left the firm last year, is familiar with the process. Rosso owns units at Bay Park, a waterfront building in Edgewater that is dealing with two offers from competing groups, each for $150 million.

“For elderly people who have lived in these buildings for such a long time, it can be a very traumatic experience, particularly accelerated with what happened with Champlain Towers [South],” Rosso said, citing both the financial and emotional aspects.

Sellers will have to change their lifestyles in many cases, giving up their waterfront views and communities they’ve built with their neighbors.

“It takes time, a lot of patience, but at the end of the day, it’s the reality,” Rosso added. “And I think people need to take advantage of this hot market and move on. As they say, you never go broke on profit.”

At Bay Park, a 254-unit building that was constructed in 1961, unit owners are facing roughly $10 million in concrete restoration work and other repairs required to bring the 13-story building up to code.

Both Bomel Companies, a Los Angeles developer, and Miami-based Aman Group, a firm led by investor Vivian Dimond, are trying to convince unit owners to sell. Bomel has secured contracts with about half of the owners, but that deal wouldn’t close unless it gets more than 95 percent of unit owners.

The building is emblematic of the dilemma individual owners of older properties are facing. Some don’t want to sell and would pay to make the necessary repairs. Others can’t afford the repairs. And some are investors looking to make a profit. But unless they come together, a bulk deal won’t happen. And if they don’t complete the restoration work, the city could eventually shut Bay Park down.

“People are going to be more reluctant to stay in these much older buildings that have deferred maintenance issues, particularly when they are the target of a condo termination,” said Berkadia broker Scott Wadler. “They may be more incentivized to walk away, to sell their unit.”

Condo associations are increasingly hiring brokers and property management firms to streamline the process and avoid bidding wars that divide sellers.

Mika Mattingly, a Colliers broker, is working with broker and investor Arden Karson on condo termination deals, encouraging owners to be a “united force, because that’s where you have the most bargaining power,” Mattingly said. “Developers will really appreciate that because they don’t have to scramble later.”

In some cases, sellers can double the market value of their units by banding together, Karson added.

“They’re not building any more beachfront. If you want to be in prime locations, you’ve got to look at these older buildings that have run their useful life,” said Collins of Two Roads. “You’ll never get a higher price. If you come together and sell it to a group as a developer, you’re going to hit a home run.”

A previous version of this story incorrectly identified attorney Bill Kramer’s firm.