An industrial design graduate from upstate New York, Brian Chesky wasn’t your typical Silicon Valley CEO when he began thinking in earnest about taking his company public.

Nine years earlier, in 2008, he had cofounded a home-sharing firm after he and a roommate invited strangers to stay on air mattresses at their San Francisco apartment to cover rent. The startup, Airbnb, had since grown to become a household name and a staple of the travel industry, with listings ranging from an igloo in Finland to a dome in the Catskills.

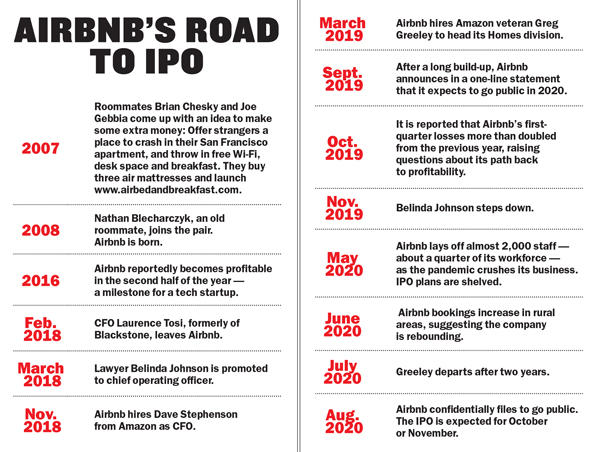

Airbnb made tentative plans for a 2018 stock-market debut. Bankers had been circling, pitching the idea for some time, according to a person familiar with the matter. The company was in a solid position, having reportedly become profitable in the second half of 2016 and raising $1 billion the next year at a valuation of $31 billion. The runway was also clear: Uber, Lyft and Spotify were yet to go public.

But Chesky had reservations, a person familiar with his thinking said. The company was plagued by regulatory disputes in New York City and San Francisco. And its Trips platform, which lets users plan experiences at their destinations, was struggling; a public filing would lay bare just how much.

Staffers, however, were getting antsy. Many had worked there for years and owned valuable stock options that were set to expire. They wanted a payout — or at the very least, an idea of when it would arrive.

“When Brian spoke of this infinite timeline, it felt a little bit like he wasn’t considering all of us who didn’t have an infinite timeline to pay off our loans, for example,” said a former employee.

But when the IPO was brought up at all-hands meetings, Chesky demurred, according to two former employees. Yes, the company was looking at it, he would say. No, it had no timetable.

—

The stock-market debuts of Lyft and Uber early the following year, 2019, were instant flops. Uber’s share price set a record for the biggest day-one fall in IPO history. Lyft stock sank on day two and has been trending downward ever since.

WeWork’s IPO then failed to make it out of the starter’s gate. After the co-working company initiated the process in April, things fell apart. Its S-1 form — a prospectus filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission that details the company’s financial information — revealed massive losses and red flags. Investors soured on the company’s business model and management under CEO Adam Neumann, who was pushed out after tales of his odd behavior, partying and drug use hit the press.

“Uber and Lyft and WeWork totally clouded the whole IPO outlook,” said Santosh Rao, the head of research at Manhattan Venture Partners. “People were turned off by all these unicorns. They did not believe anything after their sub-par IPO performance.”

“Uber and Lyft and WeWork totally clouded the whole IPO outlook,” said Santosh Rao, the head of research at Manhattan Venture Partners. “People were turned off by all these unicorns. They did not believe anything after their sub-par IPO performance.”

Meanwhile, as Airbnb edged toward an IPO, regulatory issues kept popping up in its markets around the world, pulling the company into a game of global whack-a-mole.

In some cities, including Buffalo and Buenos Aires, the startup partnered with authorities to help structure or implement new laws. In others, the relationship was fraught: New York City — one of Airbnb’s biggest domestic markets — had cracked down on short-term rentals, threatening thousands of listings and complicating the plan to go public. In neighboring Jersey City, residents voted resoundingly against Airbnb in a November referendum despite a $4 million campaign to persuade them otherwise.

For years, the company, which declined to comment for this story, had taken a proactive approach to regulatory disputes. Airbnb’s head of global policy, Chris Lehane — a former lawyer in the Clinton White House who specialized in scandal management — joined the company in 2015 and cultivated a strategy that included attack ads, opposition research and lawsuits.

“Chris’ hiring was a turning point for Airbnb in terms of its regulatory issues,” said Bradley Tusk, a political consultant and former campaign manager for Michael Bloomberg. “Before that, they were very passive. They wanted to be more aggressive. They brought in someone who is hyper-aggressive.”

By the end of 2019, Airbnb had launched legal action against several major cities — most resulting in settlements. Opposition from hosts, guests and other groups also ratcheted up: The company had been involved in some 230 lawsuits since its founding, according to a Bloomberg analysis. More than half came after 2018.

The company’s executive ranks were also choppy. Laurence Tosi, a Wall Street veteran and former CFO at Blackstone, left Airbnb in February 2018 for his investment fund, Weston Capital Partners. Shortly afterward, Belinda Johnson, a Texas lawyer who had been at Airbnb since 2011, was promoted to chief operating officer, and Amazon veteran Greg Greeley was hired to lead the company’s Homes division. Dave Stephenson, also of Amazon, was brought in as CFO in November. All four declined to comment.

Still, Airbnb dominated the market for short-term rentals, by now bubbling with younger competitors. Its head count reached well into the thousands.

Still, Airbnb dominated the market for short-term rentals, by now bubbling with younger competitors. Its head count reached well into the thousands.

One year ago this month, Airbnb announced long-awaited news: It expected to go public in 2020. But the drumbeat of bad news continued.

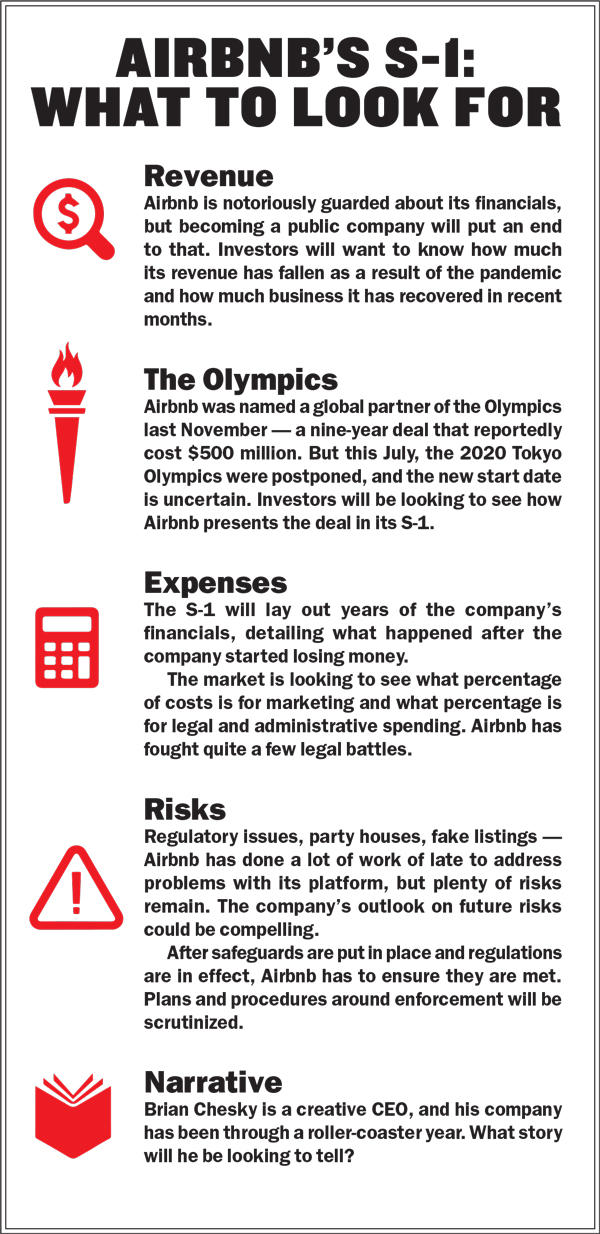

The company had always kept its financial information closely guarded. However, in October, the Information published a report suggesting the startup was no longer making money. In fact, first-quarter losses had more than doubled from the previous year to a reported $306 million. In the second quarter, it lost another $100 million. The loss was put down to an uptick in marketing expenses.

The second report coincided with an announcement from Johnson that she would be stepping down, leaving the company without a No. 2. In a statement on Airbnb’s website, she said she wanted to spend more time with her teenage children.

—

When the pandemic reached the U.S. in early 2020, it threatened to upend everything the company had built. And it just about did.

In a matter of months, global travel cratered, bookings plunged and Airbnb’s revenue in the second quarter fell almost 70 percent, according to Bloomberg.

Hosts who relied on the platform for income struggled with an onslaught of cancellations. Many wondered how they would pay their mortgages, and resented the company’s reversal of its strict, host-friendly cancellation policy. (Airbnb later apologized and started a fund for hosts.)

Desperate for cash, Airbnb raised $1 billion in equity and debt — at 11 percent interest — in an April funding round led by Silver Lake and Sixth Street Partners. Airbnb’s private valuation fell to $18 billion.

The company started offering “experiences” online. Like so many pandemic experiences, these would take place over Zoom. But virtual tours had no chance of replacing the lost lodging revenue.

Inside the company, a tearful Chesky told staff in a video call that cuts had to be made. “I have a deep feeling of love for all of you,” he told them, according to an account in the New York Times. “What we are about is belonging, and at the center of belonging is love.”

Almost 2,000 employees — about 25 percent of the company’s staff — were let go. Most worked in nonsenior positions, according to a list Airbnb published on its website encouraging other employers to hire them. The IPO was shelved once again.

In July, Greeley, head of the Homes division, left after just two years. He had reportedly questioned the company’s financial discipline.

However, his departure was mostly drowned out by Chesky’s announcement the next day that the IPO was back on the table. “We were down, but we’re not out,” he said.

By midsummer, things were turning around for Airbnb.

The stock market had rallied, triggering a stampede of IPOs from companies including Lemonade, an insurance tech startup, and Vroom, an online used-car seller.

Many enjoyed bumper results. Lemonade’s stock price soared 139 percent on its first day of trading. Vroom’s more than doubled as well.

More importantly, the short-term rental market was seeing glimmers of an upswing. Demand for domestic stays was climbing — particularly in rural areas — and cities were slowly creaking open.

Airbnb filed paperwork with the Securities and Exchange Commission — the first step to going public. Step two is to get investors excited about buying the stock.

Zach Aarons, an Airbnb investor and co-founder of proptech venture-capital firm MetaProp, predicts Airbnb will push a story of resilience in crisis.

“What I’ve been pleasantly surprised about is that Airbnb’s been able to be nimble and transform their business into more longer-term stays in rural areas instead of shorter-term stays in urban areas,” he said.

Whether or not global travel bounces back, Aarons argues, people will be moving around the country for the next year or two. “People are using Airbnb now as a way to live, whereas before they were using it as a way to travel,” he said.

But with so much of life out of whack, Airbnb’s pending offering has become intertwined with the existential questions facing the company — and, to a certain extent, the country. How can it sell travel experiences to a financially depleted, socially guarded populace? And where will the travel industry be in six months? In a year?

The shrunken company’s S-1 prospectus, which will be released when regulators finish their review, will offer critical details including revenues, losses and a blueprint for growth.

So far, analysts appear optimistic.

“Right now, the pandemic is kind of putting the business in their hands,” said Rao, noting that data shows short-term rentals have fared better than hotels during the pandemic as guests seek space and seclusion.

Dan Wasiolek, a Morningstar analyst who covers Airbnb competitors Booking.com and Expedia, said his firm predicts a full recovery in travel demand — though he concedes the projection is long-term.

Wasiolek anticipates Airbnb’s public valuation will be closer to $31 billion than its current $18 billion, “and I wouldn’t be surprised if it even gets valued a little bit above that,” he added. Rao predicted $25 billion.

To Thomas Paulson, an analyst with Inflection Capital in Minneapolis who follows consumer-based industries closely, Airbnb’s success relies on the ecosystem of restaurants, bars and music venues that draw tourists to certain areas. He believes going public before winter, when hope remains that these small businesses will survive, could be shrewd.

However, he said that if the shift away from urban destinations persists, it will hurt Airbnb’s revenue. “You have the issue when somebody travels to New York versus when somebody travels to, say, the Rocky Mountains,” he said. “They spend a lot more on their accommodation in New York.”

Projecting the travel industry’s future is especially fraught right now, a point that could spook investors. There’s also the gnawing question of profitability: Airbnb is not believed to have made money since 2018, and its path to do so again is unclear. Lots of unprofitable tech companies have gone public. But these are uncharted times.

“The rules have changed in the IPO market,” Rao said. “Investors want private companies to be profitable or have a clear path to profitability.”

Before the economy collapsed, Airbnb had been aggressively pursuing a bigger share of the travel market, buying up smaller companies as it expanded. Last year alone it acquired HotelTonight, Urbandoor and Danish startup Gaest. But several of the smaller companies that Airbnb invested in, including Zeus Living, the Wing and Lyric, have recently fallen into distress. So far, Airbnb has not bailed them out.

When the S-1 is released, commentators and analysts will scrutinize Airbnb’s marketing costs, which the startup has reportedly been working to rein in. The financials will also reveal details about spending in prior years, bringing into focus whether the pandemic triggered a major decline or just hastened one already in motion.

In retrospect, the environment for going public was far more favorable in 2018 than now. “They would have had a much easier debut in the public markets at that point,” Rao said. But, he offered, “they didn’t really need the money.”

At the moment, the market is frothy and optimistic — a fine time for an IPO. But things could change quickly if, for example, virus cases surge again.

Over the last year, Airbnb has worked hard to tidy up some of the longstanding issues that plague its platform. It banned “party houses” in November after five people were shot and killed in an Orlando rental. This June it settled a data-sharing lawsuit with New York City following settlements with San Francisco, Boston, Miami Beach and Palm Beach.

Still, regulatory issues nip at its vision for growth, and investors will need convincing that the business can thrive under tighter government rules.

Aarons, who has held stock in Airbnb since 2012, said he wishes that the company had gone public sooner, but that it did well to tackle the issues it may have considered stumbling blocks.

“I think Airbnb has done a really good job from really early on being totally upfront about the fact that the platform has issues, and tried to deal with them,” he said. “And yeah, you can say they haven’t done it fast enough and I can’t argue with that, but they’ve been a lot more forthright than the vast majority of these unicorns.”