B.C. (or Before the real estate Crash), it was axiomatic that you could sell a home for more than you paid for it in New York City.

But that truism seems shaky these days, especially for boom-time buyers. In fact, a high number of sellers are losing money on homes purchased during the defining years from 2005 to 2008, according to data from PropertyShark.

“What we are seeing a lot is that people are willing to make deals where they lose money,” said Nathaniel Faust, a broker with Citi Habitats, who has seen sellers not only sacrificing all their equity in a property, but having to show up at closings with checkbooks in hand to cover some of the outstanding mortgage debt.

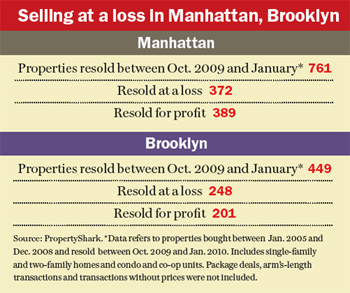

PropertyShark looked at people who sold from October of last year to January of this year and bought their homes between 2005 and 2008. In Manhattan, perhaps surprisingly, slightly more deals sold for a profit than for a loss — 389 for a profit versus 372 for a loss. In Brooklyn, those who lost money outnumbered those who sold for a gain — 201 sold for a profit versus 248 for a loss.

Still, while no one wants to lose money on a home sale, it’s possible these sales for a loss might have been shrewd moves if they helped avoid bigger problems like short sales — or worse, foreclosures.

The data, provided by PropertyShark at the request of The Real Deal, provides a snapshot of one aspect of New York’s massive sales market, and includes buyers from an up-and-down period. And some reports say the market has picked up of late, even if sales are happening at lower price points. The Corcoran Group reported that co-op sales increased 23 percent from January to February, while condo sales were up 9 percent.

Job loss can push people to take a loss on a home instead of waiting for the market to rebound. “You have to get rid of properties if you can’t afford to keep them,” said Bill Staniford, PropertyShark’s CEO.

Growing families can also necessitate more legroom, as was the case with a one-bedroom co-op near Union Square in Manhattan, which is in contract for $600,000. The recently married seller, who wants to have a baby, had paid $605,000 in 2008, said Madeline Williamson, a broker with Prudential Douglas Elliman. “It was small and they need more space right away,” Williamson said.

While the percentage of loss may be in the single digits in older buildings, it can be much larger in the types of new construction condos with glamorous in-house amenities that dominated during the boom.

Chelsea’s 555 West 23rd Street, a 14-story, 336-unit building from Douglaston Development that boasts a waterfall, fountain and fitness center, has seen a handful of units sell at a loss in recent months, according to brokers who regularly sell there.

Faust, of Citi Habitats, had been marketing a studio at 555 West 23rd Street for $569,000, though the seller paid $575,000 for the pied-à-terre unit in 2006. After factoring in brokers’ fees and seller-paid transfer taxes, the actual sales haul could be $524,000, which would constitute a 10 percent loss.

However, the seller recently decided instead to lease the unit until the market bounces back, Faust said. “It just doesn’t make sense to sell right now,” he said.

But that approach doesn’t suit everybody. In the same building, the owner of a one-bedroom, which was purchased for $915,000 in 2007 and has now been listed at $759,000, or almost a 20 percent loss, doesn’t want the hassle involved with renting his unit and hopes to unload it, said Richard Hamilton, a broker with Halstead who also lives at 555 West 23rd.

Jeff Levine, chairman of Douglaston, which no longer has sponsor units in the building, said that even a 20 percent loss outperforms some markets hit with 40 percent declines. “It’s not that disastrous,” he said. “My advice to anyone who has purchased is not to sell but to sit and wait for the market to return, which is happening as we speak,” Levine added.

At 184 Thompson Street, a Greenwich Village rental converted to a condo in 2006, a studio is listed at $599,000 after selling for $650,000 in 2007. Another there is on the market for $575,000 after last selling for $620,000 in June 2008, though the listing broker, Michael Carioti of Corcoran, defended the price. “You can get a lot for that money in the city right now,” said Carioti, adding that the seller “can probably get a one-bedroom somewhere else.”

Of course, selling at a loss, which likely involves the owner losing equity, is different from a short sale, which is when the price doesn’t cover the amount owed on the mortgage. Brokers say that, despite the market, they are not seeing that many short sales.

Still, for every person who decides to pull the trigger and sell at a loss, there might be another waiting for the market to turn. And when those units are dumped on the market later, prices could end up being tamped down again, said Staniford. He noted, “We’re still not out of the woods.”