In New York, politics doesn’t just make for strange bedfellows. For the real pros, the rapid shift in partners can put an average hot-sheets motel to shame. Just ask Peter Ward, president of the powerful New York Hotel and Motel Trades Council.

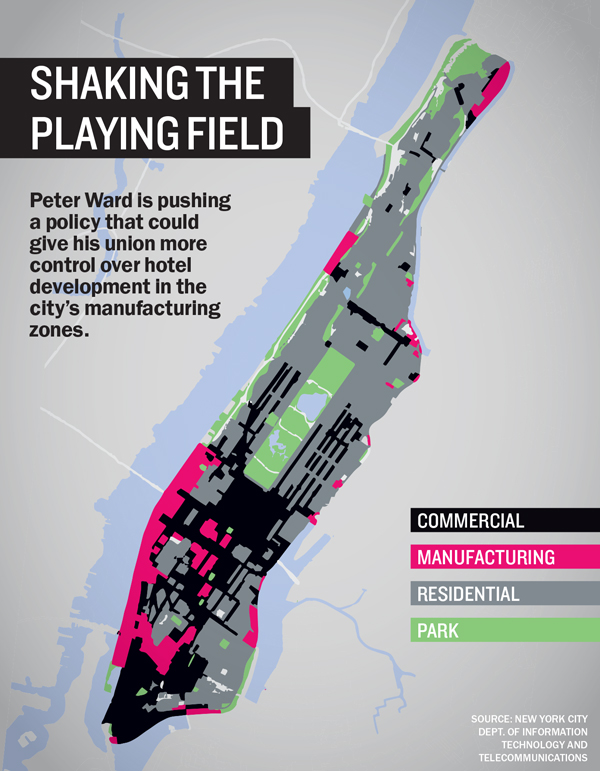

After teaming up with hotel owners and state lawmakers last year to hand home-sharing behemoth Airbnb a major setback in New York, he has hooked up with Mayor Bill de Blasio in an effort that some industry players adamantly oppose. Ward and the mayor are working to expand a policy that would require developers to get special permits to build hotels in manufacturing zones, as well as in Midtown East — where City Hall is pushing for a huge rezoning. Tellingly, the first attempt at that died in the waning days of the Bloomberg administration after Ward opposed it for its failure to include the special permit provision.

Observers say wider use of such permits could effectively hand Ward, via his well-oiled network of political connections, far greater control of when and where hotels get built across large swaths of the city.

Despite such fears, HTC’s backing for the permits has drawn little open opposition. That’s neither an accident nor unusual. Many lawmakers are reluctant to oppose the union on the issue, and hoteliers find themselves split — with some wary of crossing Ward, and others standing to gain from a measure that would likely raise the barriers for new hotels entering the marketplace.

“The reality is that the tourism industry treads lightly when it comes to workers, and they are the people supporting Peter Ward and the union,” said Douglas Hercher, an investment sales broker at the hospitality advisory firm RobertDouglas. “The last thing a hotel wants to do is pick a fight with the union and find itself in a labor slow down.”

Meanwhile, many observers speculate that if either the Midtown East or manufacturing-zone proposals go through, that could set a precedent for special permits becoming a fixture in future neighborhood rezonings across the city.

Steady climb

Ward, who declined to be interviewed for this story, became the third person to hold the title of HTC president in 1996. Since then the 59-year-old has elevated it from the status of a low-profile outfit to one of the four most influential unions in city politics.

Meanwhile, he draws his power — as well as his income — from not one but three interconnected positions he holds: president of HTC, business manager of the hotel restaurant and bar workers Local 6 in New York City, and recording secretary for North American UNITE HERE union representing hotel and food-industry workers in the U.S. and Canada. All told, he earned nearly $440,000 in salary in 2015 from the three affiliates, according to their tax filings.

Meanwhile, he draws his power — as well as his income — from not one but three interconnected positions he holds: president of HTC, business manager of the hotel restaurant and bar workers Local 6 in New York City, and recording secretary for North American UNITE HERE union representing hotel and food-industry workers in the U.S. and Canada. All told, he earned nearly $440,000 in salary in 2015 from the three affiliates, according to their tax filings.

Not bad for a kid who grew up in Marine Park, Brooklyn, and worked briefly as a waiter and bartender straight out of high school. His fortunes took a fateful turn in 1979, when he took a job as a clerk at Local 6. There, he saw his first significant action when the union brass dispatched him to help with a labor dispute at Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn.

“I think they sent me because I could find my way to Brooklyn,” he told The American Prospect magazine in 2011.

In 1978, HTC’s business agent, Vito Pitta, won election as its president. Five years later, Ward married his daughter, Debra, at a posh affair at the Plaza Hotel. Twelve years later, Pitta resigned in favor of his son-in-law. By the turn of the millennium Ward stood well on his way to turning the union into a political powerhouse, getting it more involved in backing candidates for elected office and allying itself with high-powered lawmakers, including then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Ward vigorously supported Bloomberg’s land-use policies such as the Willets Point rezoning in Queens that the City Planning Commission approved in 2008.

Today, HTC ranks alongside three other unions powerful enough to almost always have an open door to lawmakers in the hopes of significantly influencing legislation — the property-services union 23BJ, the healthcare workers’ 1199SEIU, and the United Federation of Teachers.

With 30,000 members, HTC weighs in as the runt of the litter, but under Ward it punches above its weight. Observers say that Ward’s focus on tapping politically savvy outsiders to orchestrate HTC’s policy initiatives rather than filling such roles with long-time union staffers helps. A prime example is Neal Kwatra, who won widespread plaudits as HTC’s political director, before going on to high-profile positions with Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Crucially, the union advances its agenda with tightly organized campaigns that can put boots on the ground in key races and help forge powerful alliances.

Kwatra’s successor, former HTC Political Director Josh Gold, was essentially lent out to de Blasio’s controversial Campaign for One New York nonprofit, which the mayor shut down after critics raised red flags over possible pay-to-play abuses. In January, Ward, himself, starred in one of the biggest demonstrations of HTC’s power and influence when he headed to Trump Tower to meet with the president-elect. Ward took with him labor lawyer Vincent Pitta, his brother-in-law, whose law firm and lobbying business both do well-compensated work for the Hotel Trades Council.

HTC also gets good use out its own diverse membership. When it comes time to knock on doors to get out the vote or to make a point on the street, the union can send Latino members to Latino neighborhoods, Jewish members to Jewish neighborhoods, and so on.

Hotel relations

A staunch pragmatist, Ward can lurch quickly from close collaborator with hotel owners to a hardline opponent. Notoriously, he forced the shut down of the city’s once-highest-grossing restaurant, Tavern on the Green, in 2010 after the new operator threatened to cut wage and benefits for its 400 unionized staffers. Similarly, some observers blame his union’s hardline stances for service cutbacks at some of the city’s premier hotels. The New York Hilton Hotel Midtown, for example, dropped room service from its restaurant four years ago. And the Hudson Hotel on West 58th Street cut back on its food-and-beverage operations as costs rose.

Meanwhile, at a Bronx hot-sheets motel caught up in a labor dispute with the union, members snapped photos of patrons stopping by for short stays and posted them online.

Meanwhile, at a Bronx hot-sheets motel caught up in a labor dispute with the union, members snapped photos of patrons stopping by for short stays and posted them online.

Nearly two years ago, the union flexed its muscle with influential lawmakers to win City Council passage of a bill that slapped a two-year moratorium on the conversion of large hotels into residential properties – a measure designed to thwart conversions like that of the Plaza Hotel. It’s also worth noting that the bill’s sponsor, Chelsea Council Member Corey Johnson, is rumored to be in the running to become the next Council Speaker.

Reacting to the hotel conversion moratorium at the time, the Real Estate Board of New York shot back with a lawsuit challenging that the law was unconstitutional and “procedurally defective,” at the very same time that REBNY and HTC were working hand-in-hand in Albany for passage of state legislation to make it illegal to advertise short-term rentals on sites like Airbnb — a business that the hotel industry claims unfairly eats into its profits.

REBNY president John Banks called that seemingly inexplicable contradiction nothing less than “a great example of Peter’s acumen and shrewdness,” adding: “He didn’t let the fact that we were litigating against him prevent us from working in a cooperative way.”

To Banks, Ward is a force to reckon with.

“Anybody who’s worked with Peter on the same side of the table would describe him as very shrewd, very smart,” he said. “I would love to have him on my side in any fight.”

In vintage Ward style, the campaign against Airbnb roped in some other odd bedfellows, including the Hotel Association of New York City — the industry lobbying group that typically sits on the other side of the table from the HTC. Yet even in that adversarial setting, the union boss has managed to forge some remarkable deals. Among those was a collective bargaining agreement reached with HANYC in 2012, which was extended three years later for another decade.

“The length and scope of the agreement is unprecedented in labor/management relations in New York City,” HANYC president Vijay Dandapani said.

What made it possible, several people familiar with the deal say, is the sophisticated health care plan Ward has put together for his members. The plan provides coverage for members at rates that are roughly 40 percent below the city average — an achievement that helps lower and stabilize a key element in the cost of labor.

In gratitude, two years ago, developer Steve Witkoff went so far as to invite Ward to join a select group, including the mayor, at the ground breaking for his Times Square Edition hotel.

“Peter basically created a managed healthcare business,” Witkoff explained. “Why is that so big? Because what an owner cares about is predictability in wages and that’s what he’s been able to do to get a much longer duration in his contracts.”

Special permission

For all Ward’s successes, however, he has fallen curiously short when it comes to cashing in on the huge growth in the city’s tourism sector. This year, New York is expected to welcome 61.7 million tourists, up from 48.8 million in 2010. Meanwhile, the number of hotel rooms has jumped from 76,500 in 2008 to 112,000 this year. But Ward has done little to unionize hotels in the outer boroughs where many of those new rooms were added. Even now, the union counts just one hotel in Brooklyn and a handful in Queens, mostly around the airports.

A special permit would ostensibly allow the unions to get a larger slice of that pie. The argument goes that if a developer wants to build a hotel in a manufacturing zone, he or she would have to get approval from the local council member, who would grant it on condition that the hotel is a union shop.

Many high-profile hotels, including the Standard in the Meatpacking District and the NoMad and Ace hotels in NoMad, have gone up in manufacturing zones. Ward’s motive, however, might not be to unionize more hotels, but instead to limit competition for the ones he already oversees, according to several sources.

The city put special permit requirements in place when it rezoned 25 blocks in north Tribeca in 2010, and again in 2013 when it rezoned 18 blocks in Hudson Square. But a spokesperson for the Department of City Planning said the agency has no record of any special-permit applications completed or currently in the works in those areas.

A former employee of the HTC affiliate UNITE HERE who spoke on the condition of anonymity suggested that Ward, in all his wheeling and dealing, may be more interested in limiting competition for the hotel’s employing his members rather than in signing up new ones.

“He doesn’t focus a lot on organizing non-union hotels. He fights for really expensive contracts,” the former employee said. “He uses [his clout] to get really good contracts for his workers.”

But in pushing for wider use of special permits, Ward isn’t facing much pushback. REBNY said it’s against special permits limiting development, but doesn’t appear to be opposing the measure with any force.

“Generally, we oppose the application of special permits to any development scheme or zoning change because in our view, the world of development needs less encumbrances on it,” Banks explained.

One of the city’s most prolific hotel developers, John Lam of the Lam Group, said he fears that such permits could drive up his costs and ultimately his room rates.

“It’s ridiculous,” he said. “We hear from a lot of tourists who complain that [Manhattan] is too expensive, and they’re having to stay in New Jersey or different boroughs.”

Ward has ways to bring opponents to heel. The union is currently boycotting one of Lam’s hotels on West 25th Street in Chelsea. Though Lam declined to comment on that dispute, it’s worth noting that his company is developing a 465-key Virgin Hotel — one of the biggest hostelries in the city’s pipeline — just a few blocks away in NoMad.

Will the staff at the Virgin be unionized?

“I don’t know yet,” Lam said. “We’re still figuring that out.”

(To see a selection of hotels under construction, click here)