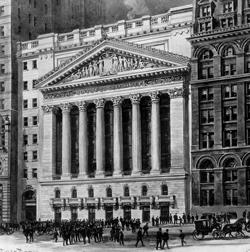

1903: NYSE reopens in new Broad Street building

NYSE Building at 18 Broad Street

The New York Stock Exchange officially opened its doors for business 116 years ago this month, the New York Times reported. To celebrate, 2,000 people assembled inside the new building at 18 Broad Street for the dedication ceremony. Outside, ticker tape and wads of paper were thrown from neighboring windows as makeshift confetti, while crowds gathered nearby on Wall Street. NYSE president Rudolph Keppler symbolically banged an ivory and gold gavel to commence business — the same gavel that closed business in the old exchange at 10-12 Broad Street. Keppler described the new exchange, designed by George Post, as an “imposing structure”fitting of the institution and the country’s ascension in both global finance and diplomatic affairs. “The magnificence of our new home is only in keeping with the magnitude of our business,” Keppler told the gathering. Founded by 24 brokers in 1792, the NYSE expanded rapidly in the late 19th century as listed stocks skyrocketed in popularity, with trading volume tripling between 1896 and 1899. The NYSE also had its own ballooning business costs. When demolition of the old exchange began in 1901, the project was expected to take a year and cost $1 million. But delays caused work to drag on, and the final deconstruction cost soared to $4 million.

1969: Governor seeks $600M for subways

Gov. Nelson Rockefeller

New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller urged the state legislature to pass a multifaceted transit bill to expand New York City’s subway system, the New York Times reported 50 years ago this month. Transit was one of Rockefeller’s pet projects, and the $600 million cash infusion came about a year after the legislature created the Metropolitan Transit Authority. The MTA as a new entity was a victory for Rockefeller in wresting control of the city’s transportation network away from omnipotent city planner Robert Moses, and today, it is a sign of Albany’s control over the city’s public transit. Rockefeller’s new expansion plan for New York’s subways was expected to cost $1.4 billion and include longer lines throughout all the boroughs, as well as a “new” Second Avenue subway. But within the year, political maneuvering and conflicting demands from city residents would stymie that Second Avenue subway plan. Construction only began in 2000, and the first of two phases opened in January 2017. More broadly, the state of the city’s subway system has turned into a full-blown crisis with the task of modernizing an outdated transportation network, which is expected to cost around $40 billion and take a decade to execute.

1978: Section 421 benefits the “young, well paid and highly educated”

Affordable apartments

New York City’s main vehicle to create housing is called into question by a Rutgers University study, the New York Times reported 41 years ago this month. The 1971 advent of the Section 421 tax-exemption program for landlords and developers was found to largely benefit the “young, well paid and highly educated” who lived in Manhattan, the Times reported, citing the Rutgers analysis. The goal of Section 421 was to stop city residents from moving to the suburbs. In Manhattan, the average rent in a Section 421 building was around $500 for the duration of the study, from 1971 to 1977, 57 percent higher when compared to the $320 residents paid in other boroughs. Residents’ median household income was around $24,270 — or just over $98,000 today when adjusted for inflation. In subsequent decades, the exemption program evolved to become a vehicle the real estate industry claims is necessary to build affordable housing, while critics contend the benefits disproportionately favor developers and are responsible for an excess in market-rate housing stock. The program, now known as Section 421a, remained in effect until 2016. The tax break was reincarnated in April 2017 as the “Affordable New York Housing Program.”