From left: 360 Smith Street, 73 Pineapple Street, 303 East 51st Street, Beekman Tower and 189 Schermerhorn Street

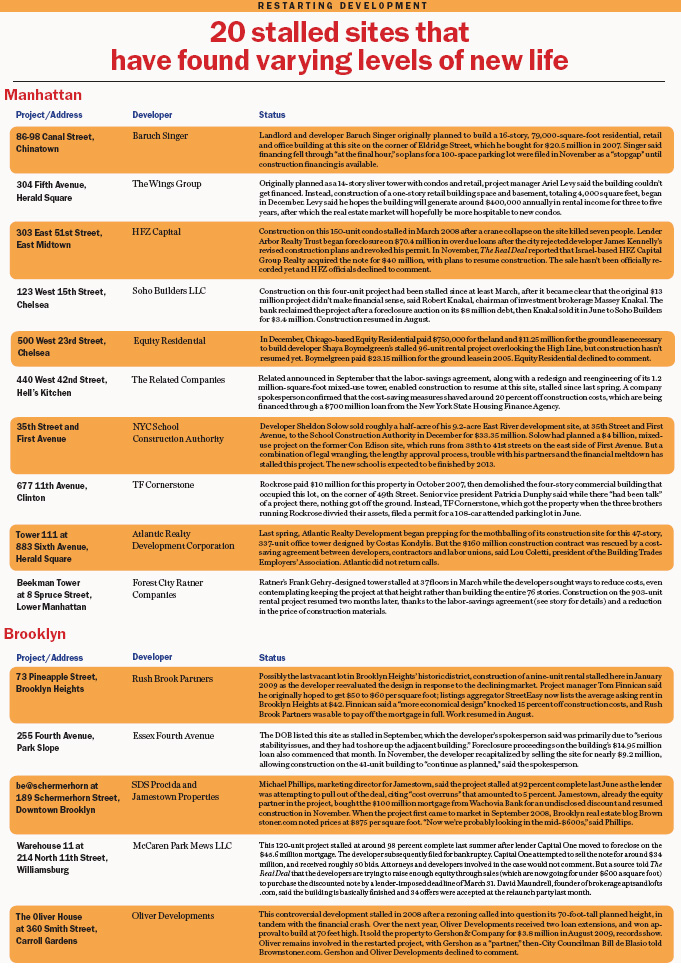

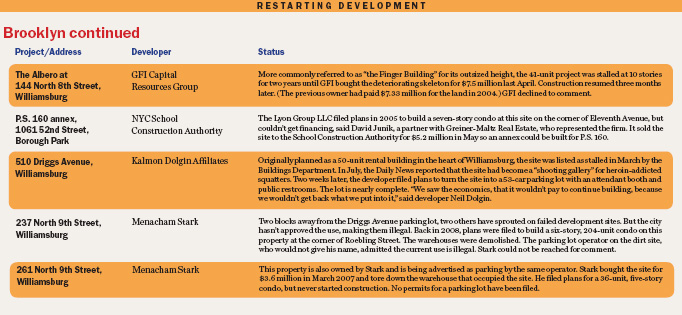

Hundreds of dormant construction sites still dot the city, but a handful of these beleaguered projects are finally seeing new life — even if it’s not what was once dreamed of for the location. Those that have seen some type of resolution were able to do so by selling off their debt at steep discounts, slimming their construction costs or setting their sights way lower.

This month, The Real Deal tracked down 20 stalled projects that have seen some type of resolution within the past several months (see chart below or click here).

Eight of those boarded-up sites are in the process of becoming parking lots, city schools or low-slung retail — so-called “taxpayers” because the monthly rent they are getting is merely intended to cover carrying costs while the owner awaits a better market.

Nine projects were either snapped up by new, bargain-hunting owners, or saved by well-capitalized equity partners who bought the debt at a discount while retaining partnership with the existing developer.

And the last three projects were jump-started thanks to an agreement finalized in March between labor unions, contractors and developers that shaved up to 20 percent off the cost of building.

This labor pact has been helping developers retain profitability in the face of a declining real estate market. But it has done little to resurrect the roughly 530 projects that the city Department of Buildings lists as stalled.

As a result, the construction industry is strongly considering further lowering their rates when the agreement comes up for renewal in March, said Lou Coletti, president of the Building Trades Employers’ Association of New York.

“If we don’t extend this agreement or come up with a new one, the unionized construction industry in New York City will be significantly diminished,” he said, adding that its roughly 30 percent unemployment rate could grow to 50 percent by the end of this year (see “Construction firms get modest”).

Below is an account of how some developers at once-stuck projects managed to figure out either long-term solutions or Band-Aids until the market turns.

Narrowing the divide

By and large, industry experts say that stalled development is tough to revive right now because construction financing is scarce. In addition, the parties involved want more money than new investors — and the market as a whole — indicate the project is worth.

But that gap appears to be slowly narrowing, according to some investors seeking stalled projects, with the going rate around half off peak prices.

Robert Knakal, chairman of investment brokerage Massey Knakal, sold a long-stalled four-unit project in Chelsea for $3.4 million in June — 57.5 percent less than the $8 million debt the lender foreclosed on. Construction on the four-unit condo resumed in August.

Robert Knakal, chairman of investment brokerage Massey Knakal, sold a long-stalled four-unit project in Chelsea for $3.4 million in June — 57.5 percent less than the $8 million debt the lender foreclosed on. Construction on the four-unit condo resumed in August.

Also in Chelsea, Chicago-based Equity Residential paid $11.5 million last month for the ground lease to build the 96-unit High Line project that developer Shaya Boymelgreen was planning. Construction hasn’t resumed yet, but the purchase price was 51 percent less than what Boymelgreen paid for the ground lease in 2005.

“We are seeing with projects that are underwater [mortgaged for more than they are worth], banks are not disclosing prices, but they are listening to any kinds of offers that we have,” said Andres Hogg, head of U.S. operations for Espais. Hogg said Espais, the developer behind the nearly sold-out Twenty9th Park Madison, is looking to invest around $50 million in stalled projects.

“Six months ago, [lenders] were barely trying to discuss it, because they were trying to find a solution with the existing developer,” said Hogg, who noted that the existing developer is oftentimes angling to buy out the debt with new equity partners. “Depending on how advanced the project is, [the banks] are less interested in talking to us.”

Based on admittedly limited information — only 300 distressed assets nationwide — banks have had the second-highest rate of recovery when liquidating distressed assets in the New York metropolitan area, 70 percent, compared to a 59 percent national average, according to Real Capital Analytics. Los Angeles was No. 1 at 73 percent.

“Investors do recognize the long-term value of New York City property, and are willing to move up the risk spectrum a little bit more to get their hands on these assets,” said Dan Fasulo, managing director at Real Capital Analytics. “A distressed project in New York has less risk than a similar project in Detroit.”

However, the Real Capital Analytics report notes that as banks tackle increasingly troubled properties, their recovery rate, or the percent of money they lent that they are getting back, is dropping. Fasulo said the ones being resolved the quickest these days “are the ones where, if the lender takes over the project, something needs to be done to recover the value.”

The site of the infamous 2008 crane collapse, 303 East 51st Street, is one such project. Stalled for 22 months and in foreclosure, The Real Deal reported in November that Israeli-based HFZ Capital agreed to acquire the note from Arbor Realty Trust for $40 million — 43 percent less than the amount in overdue loans. HFZ officials declined to comment.

Hogg, along with another developer who looked at the site, which has been stuck at 19 stories since the collapse, said only a steep discount — “30 cents on the dollar” — would sufficiently cushion the project from financial failure given its level of deterioration and legal and zoning issues that need to be worked out.

For these reasons, vacant lots and foundations can be simpler transactions.

“We are looking at purchasing some vacant lots, and the value of that lot is 50 percent off what it was valued at the peak, and I think that is the maximum that we would be willing to pay,” said Hogg.

The New York City School Construction Authority is also in the market for vacant lots, and has snapped up several within the past year where construction never got off the ground. They include $33.4 million for a half-acre of developer Sheldon Solow’s troubled 9.2-acre East River project, and $5.2 million for land in Borough Park where condos had been planned.

David Junik, a partner at Greiner-Maltz Real Estate who has sold several distressed sites within the past year, including the one in Borough Park, said he has two privately listed, stalled warehouse conversions in Williamsburg where the bank shaved 36 percent and 67.5 percent off what it was asking a year and a half ago.

“Banks are beginning to realize that they don’t want to sit with dead money for too long,” said Junik. “And now we are beginning to see that apartments are beginning to sell at huge discounts, but they are selling,” which has finally provided some barometer for how much a property should be discounted.

Setting the barometer

Warehouse 11

One project setting the barometer is Warehouse 11 in Williamsburg, which stalled last summer at around 98 percent complete while lender Capital One attempted to foreclose on the property and the owners filed for bankruptcy protection.

Now priced at 21 percent less than the original $709-per-square-foot asking price (or less than $600 per square foot), apartments are selling briskly. The scene at the 120-unit condo’s relaunch party last month was like a sample sale for interior designer Andres Escobar.

Dozens waited in the frigid weather for the doors to open, then crowded the moodily lit office to fill out mortgage applications, waving around checkbooks while house music bumped in the background.

David Maundrell, president of the brokerage aptsandlofts.com, said the sales team had more than 350 appointments to view apartments that night, and they accepted 34 offers, contingent on financing.

Months earlier, developers Yitzchok Schwartz and Isack Rosenberg of McCaren Park Mews LLC were fighting Capital One in court for the right of first refusal to purchase the project’s $45.6 million note, which the bank was marketing through Massey Knakal for around $34 million, according to court documents.

But Capital One had attempted to prevent the developers from even entering the property, accusing the duo of stealing appliances and letting a leakage problem fester in order to devalue the property. Attorneys and developers involved in the case would not comment on the exact nature of the resolution. But a source told The Real Deal that the developers are trying to raise enough cash through sales to buy the discounted note themselves before a lender-imposed deadline of March 31.

Maundrell said the building is basically finished, and received its certificate of occupancy in November.

Similarly, construction at be@schermerhorn in Downtown Brooklyn also stalled and then resumed when it was more than 90 percent complete.

Michael Phillips, marketing director for Jamestown Properties, the equity partner on the project, said the building is expected to be marketed at “the mid-$600s” per square foot, 26 percent less than when it first came to market in September 2008, the same week Lehman Brothers collapsed.

Phillips said the project, developed by SDS Procida, stalled at 92 percent complete last June as the lender attempted to pull out, citing 5 percent cost overruns. Jamestown, already an equity investor in the project, was well-capitalized enough to purchase the $100 million mortgage from Wachovia Bank at an undisclosed discount, and construction restarted in November.

He said they are in the process of installing the last fixtures, and will relaunch sales once an amendment to the offering plan is approved.

Prime parking

While some developers sitting on vacant lots may have had grand visions of erecting sleek condos with fancy amenities before the downturn, those dreams have been downsized.

If an owner can afford to keep a property rather than selling it for a loss, sometimes the best option is to convert it into a parking lot, or a one-story “taxpayer” building with room for a retail tenant who will provide enough rental income to cover the carrying costs.

The Wings Group, a partner in the Brompton on the Upper East Side, originally planned to erect a 14-story sliver tower with apartments and retail at 304 Fifth Avenue, but couldn’t get construction financing once the real estate market tanked. So, project manager Ariel Levy said the firm is now constructing a one-story retail building with a basement — 4,000 square feet in total that will cost less than $300,000 to build — with the hopes of earning around $400,000 annually in rent until the economy turns.

“We’re not looking to put up what is going to be your state-of-the-art building here,” said Levy, adding that potential tenants include nail salons, small grocers or souvenir shops, given the location’s proximity to the Empire State Building and Koreatown.

“We don’t want to sell the property at a loss when we know that in three to five years it’s going to be a different game,” he said.

In 2007, the firm paid $7.5 million for the property, which was then occupied by a four-story building.

Parking can also bring in a decent chunk of change — monthly rates run around $250 for a regular-size car in the areas where The Real Deal found stalled-sites-turned-parking lots, estimated Brian Ezratty, vice chairman of investment brokerage Eastern Consolidated.

At Canal and Eldridge streets, landlord and developer Baruch Singer tore down a tattered five-story building in the hopes of replacing it with a 16-story, 79,000-square-foot mixed-use tower. He lost financing “in the final hour,” and in November, filed plans for a 100-space parking lot.

“The parking is only a stopgap measure until you can get construction financing and the market comes back,” said Singer.

In Williamsburg — the neighborhood with the highest concentration of stalled projects — there are at least three such parking lots within two blocks of each other. One, at 510 Driggs Avenue, was supposed to be a 50-unit rental building.

The other two, at 261 and 237 North 9th Street, where 240 apartments were planned in two buildings, do not have permits from the city.

“The city gives us a lot of headache because they are not looking to give you a permit,” said the operator of those parking lots, who would not give his name. He said he runs “tons” of parking lots on stalled sites in Brooklyn and is looking at opening more. “Flatbush Avenue, all of Clinton Hill and Park Slope” are ripe for the picking.

“I know of a couple of sites that were parking lots, deals fell through, and now continue to be parking lots,” said Ezratty. “But it’s very hard to get a Certificate of Occupancy to park cars when you haven’t had one previously,” he said, explaining that the city is not eager to park cars where towers were supposed to rise.

Labor savings

Tower 111

Several stalled projects that already had significant financial backing were able to resume construction with the help of the much-ballyhooed labor-savings agreement that is up for renewal next month.

That agreement, which saved developers between 10 and 20 percent on building costs, has already been implemented at 36 projects citywide totaling $6 billion worth of construction contracts as of press time. In addition, seven new contracts were pending, said Coletti of the Building Trades Employers’ Association.

Only three of the projects where the agreement is in effect — Tower 111, Beekman Tower and Related Companies’ 42nd Street tower — appeared to have actually been stalled for an extended period of time. And the latter two projects already had a combined $1.38 billion in government financing.

But Coletti said many more of the projects on the list were on the verge of being stalled. “Clearly the cost of construction is going to have to continue to go down if we’re going to give a developer any opportunity to move forward on a [stalled] project,” he said.

In addition to much stricter financing requirements, rents and residential sale prices have dropped by around a quarter since most of the stalled projects were conceived.

Forest City Ratner Companies, for example, originally expected to get $80 per square foot for its 903-unit Beekman Tower rentals, according to the New York Times. Today, the listings aggregator StreetEasy pegs the average asking rent in the Financial District at $50 per square foot (although none of those buildings have a wavy façade designed by Frank Gehry).

The 76-story tower had stalled at 37 floors in March while Ratner sought ways to trim costs. It was among the first projects to take advantage of the labor-savings agreement.

“We’ve received fewer and fewer [new contracts] as we’ve moved forward, and that was a clear indication to us this [agreement] was nothing more than a Band-Aid,” said Coletti. “It had helped us avert an immediate unemployment crisis, but in the longer term it pushed that crisis back to 2010 and longer.”

Click charts below to view larger versions