The Jean Nouvel tower at 100 Eleventh AvenueOutside, a late-January snowstorm has left a delicate frosting on the shimmering gray-green jumble of steel and glass that is 100 Eleventh Avenue, making the newly constructed condo tower all the more eye-catching in the flat winter light.

Inside, however, fat drops of water fall from the ceiling, forming a puddle on the polished-granite floor of the Jean Nouvel-designed lobby.

Todd Eberle, a photographer who lives on the fourth floor, eyes the leak with concern.

“I don’t know what that’s about, but it’s not good,” he says.

A photographer-at-large for Vanity Fair who has spent much of his career shooting architecture, Eberle is an avowed Nouvel devotee. Before moving into 100 Eleventh Avenue in the summer of 2010, he and partner Richard Pandiscio lived at 40 Mercer, another Nouvel-designed condo. They love their new apartment, its terrace with views of Frank Gehry’s IAC Building, and the way changing patterns of light dance across the floor.

Yet Eberle is one of a number of residents voicing concerns about the building. They claim Nouvel’s design has not been executed properly due to delays and cost-cutting by the developers, Cape Advisors. These shortcuts have led to shoddy workmanship, they say, a viewpoint echoed in a number of lawsuits and applications to the Attorney General for the return of deposits (provided to The Real Deal under the Freedom of Information Law). It’s an opinion that Jean Nouvel himself has publicly expressed.

The developers “have gone off course,” he recently told the New York Times. “They want to complete the building as inexpensively as possible and they want to take the money.”

As the aftermath of the financial crisis roiled New York, new condos like the Plaza and the Brompton made headlines when their buyers began backing out of contracts. But troubles at 100 Eleventh Avenue have largely flown under the radar as critics gushed over Nouvel’s stunning design. During the real estate boom, the building’s starchitecture pedigree and luxurious amenities lured celebrities and billionaire buyers, and more than 70 percent of its units had been sold at record prices when Lehman Brothers crashed. But, as at many new condos, the financial crisis plunged it into a stew of delays, cash shortfalls, broker turf wars and buyers demanding their money back.

Cost overruns at 100 Eleventh Avenue sent Cape Advisors looking for new capital just as the financial crisis enveloped the city. More than half of the buyers in contract attempted to back out, according to people familiar with the matter, causing a number of deals to fall through.

Developers attribute that to buyers wanting to get their money back as property values were declining.

“The disputes were nothing more than buyer’s remorse,” said the attorney for the sponsor, Jay Neveloff of Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel.

The project was on the verge of collapse when an unlikely hero emerged in the form of Howard Lorber, chairman of Nathan’s Famous, the Vector Group and Prudential Douglas Elliman, the city’s largest residential brokerage. At a crucial moment, Lorber and partners brought some $30 million of new funds to the project, allowing construction to continue.

Lorber and his partners “white-knighted it,” said one industry insider. “They really saved the deal.”

A house of glass

Details of 100 Eleventh Avenue’s exteriorIn many respects, 100 Eleventh Avenue is a success story. It could easily have stalled, like other ambitious starchitecture projects such as 56 Leonard Street, a Jenga-like tower by Herzog & de Meuron, and Dutch starchitect Ben van Berkel’s 5 Franklin Place.

Instead, the tower was completed and owners are now ensconced in their new homes. “Frasier” star Kelsey Grammer recently bought in the building, and only 13 of the building’s 54 units remain unsold, Elliman said.

But the building is also a clear example of the challenges faced by new condos seeking to overcome the tenacious legacy of the financial crisis.

A review of lawsuits, complaints to the AG and conversations with current residents reveal a litany of alleged problems.

Owners complain of leaks in the ceilings and in the much-vaunted glass-curtain wall — the centerpiece of Nouvel’s design. And several of the lawsuits argue that Lorber’s involvement in the project amounts to a change of control, which should have automatically given purchasers their deposits back.

Residents’ concerns about the project became public recently when Upper East Side designer Jennifer Post was hired to redesign the lobby, angering Nouvel purists. Nouvel’s firm and others say the original plans for the lobby and adjoining garden were never properly implemented, even before the changes were made.

“There’s a lot of little details that we think would have been very important and have not been done,” said François Leininger of Ateliers Jean Nouvel, the project architect. For example, he said, “the garden was not done the way we designed it.”

Current residents say all they want is to have the problems addressed. But if that doesn’t happen soon, more lawsuits loom on the horizon.

The complaints and suits that have surfaced so far are “the beginning of what we’re going to see,” said one resident, who asked not to be named.

The developers deny that the changes they made disrupted Nouvel’s design.

“We worked very quickly with Jean and gave him 95 percent of what he was looking for,” said Craig Wood of Cape Advisors. “There were very minor changes that were made at the end. It was more dictated by positioning and marketing the building than anything else.”

As far as current residents’ complaints go, he said: “We’ve built a building that if it’s not a landmark now, will be a landmark someday, and buyers have responded to that. That’s not to say that there aren’t small things and punch-list things, which we believe we’ve been extremely responsive to. We want [residents] to be happy.”

It’s not uncommon for developers and residents to disagree about what’s a minor item and what’s a serious problem. And, lawsuits between condo residents and developers are becoming increasingly common as condo boards take over their buildings from sponsors, often discovering construction defects or budget problems. In fact, in August 2010, Cape Advisors was sued by the condo board at another of their buildings, 210 Lafayette Street, also known as One Kenmare Square, for $600,000 for alleged “breach of contract, negligence, fraud, negligent misrepresentation, unjust enrichment, and wrongful distribution of assets in connection with the construction and sale of condominium units.” The suit appears to be ongoing.

During the boom-time sellers’ market, buyers signed contracts giving them few options if the sponsor didn’t complete the building as they expected, said attorney Brian Kishner, who represented 100 Eleventh Avenue buyer Jose Carlos Guzman in a December 2009 lawsuit.

Kishner said he could not talk about the Guzman suit (which has now been resolved) because of a confidentiality agreement. But in court documents, Guzman alleged that the sponsor and selling agents committed fraud by intentionally deceiving him, and said he was entitled to the return of his $710,000 deposit because a Chelsea Piers billboard blocked the water view from his sixth-floor apartment after sales staff explicitly told him that it wouldn’t.

Vying for “Vision Machine”

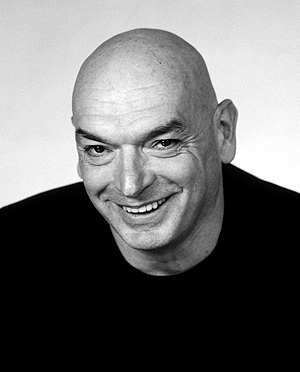

Jean NouvelIn December 2005, Cape Advisors acquired a plot of land next to Frank Gehry’s distinctive IAC headquarters in Chelsea, reportedly for $47 million.

Last year’s lawsuit aside, the 53-unit One Kenmare Square in Soho sold out by the time it was completed in 2006 and was considered a success for Wood and his business partner, Curtis Bashaw. Cape Advisors also owns the Chelsea Hotel in Atlantic City and several hotels in Cape May, N.J.

The duo hired renowned French architect Jean Nouvel to design a condo for the 19th Street site, which overlooks the Hudson River and Chelsea Piers.

Nouvel nicknamed the building the “Vision Machine.” The design called for 1,700 uniquely sized glass panes — some up to 37 feet wide — set at unique angles to reflect the light and create a gleaming façade.

The plan was a sensation. (The New York Times’ architecture critic, Nicolai Ouroussoff, called the building “a lesson on how to navigate an enlightened path in an era of extremes.”) Sales began in 2007 to much fanfare, and boldfaced names like fashion photographer Mario Testino signed up to buy apartments at prices averaging more than $2,700 per square foot.

With Corcoran Sunshine handling sales, more than 70 percent of the units went into contract, according to multiple people familiar with the project. When Nouvel won the 2008 Pritzker Architecture Prize, one of the field’s top honors, it only added to the project’s cachet.

But the Vision Machine faced problems from the moment construction crews dug into the ground. Instead of bedrock, they hit mud and water. The Wall Street Journal reported in August 2008 that the project was $50 million over budget and a year behind schedule, and that iStar Financial was forcing the developers to refinance their construction loan with higher rates.

Cape Advisors “ran out of money,” said one industry source. “They were out in the market pretty heavily looking for new equity.”

Construction was on the verge of being halted when Lorber and his partner Michael Strauss stepped in.

In September 2008, a subsidiary of Lorber’s New Valley LLC (the same entity that owns half of Elliman) purchased a 40 percent interest in New Valley Oaktree Chelsea Eleven LLC, according to New Valley’s website. That entity then lent $29 million and contributed $1 million in capital to Chelsea Eleven LLC, the managing member of the sponsor of 100 Eleventh Avenue.

The deal allowed construction — and sales — to continue. Corcoran Sunshine was removed from the project and replaced by Elliman. (Lorber’s son Michael is one of the Elliman agents now selling units at the property.) The building’s original $110 million loan from iStar Financial was paid off last June, Wood said. Then, in July, with 26 of the 54 units closed, commercial investment firm Pembrook Capital Management agreed to provide a $47.1 million, 24-month recapitalization loan for the project.

Lorber’s involvement is somewhat controversial, however. The AG’s regulations state that if there is a material change in the ownership of a new condo, buyers in contract are allowed the right of rescission, meaning they can opt to get their money back, explained real estate attorney Allison Scollar. Whether the right of rescission is triggered depends on the way a deal is structured, she said, explaining that the addition of new lenders or investors doesn’t necessarily amount to a change in ownership.

Lawsuits filed by buyers at 100 Eleventh Avenue alleged that Lorber and his partners have taken the reigns of the project and become the “de facto” sponsor, but kept this fact from buyers to avoid triggering the right of rescission.

A lawsuit filed by buyer Roseann Barber in April 2010 argued that amendments to the offering plan “[failed] to disclose the material facts that there are additional parties with ownership interests in the Sponsor, namely Vector Group Ltd., New Valley LLC, and New Valley Oaktree Chelsea Eleven LLC, who are … now in control of the project.”

In another case, attorney Bruce Cohen argued in a March 2010 application to the AG for the return of his client’s $591,750 deposit that “the sponsor did not disclose the change in control because it knew that such a change is material and warranted an offer of rescission.”

But when asked about the project last month, Lorber said he is “just a lender.”

“My company has made a loan to help the building get finished,” he said.

Wood also said Lorber and partners “were a lender to the project, and like many lenders, they have an active role. We certainly consult with them on an ongoing basis.”

In his client’s application, Cohen also claimed that the sponsors didn’t disclose the identities of the new investors in part because Strauss — the former CEO of now-bankrupt American Home Mortgage Investment Corporation — had been investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. In 2009, Strauss agreed to pay $2.45 million to settle fraud charges brought by the SEC, which alleged that he had engaged in accounting fraud and concealing the worsening financial condition at AMH as the subprime crisis emerged.

Cohen also argued that the sponsors failed to adequately disclose the relationship between the new investors and Elliman. Other sources said, in practice, that relationship may have created a conflict of interest when Elliman took over sales at the project. Several sources familiar with the matter said that as head of Elliman, Lorber had an incentive to see the deals done by Corcoran replaced by new deals brokered by Elliman agents.

Neveloff disputed that notion. “No seller I’ve ever met wouldn’t take a sale that was [in contract],” he said.

Buyer complaints

Howard LorberAs construction soldiered on, some buyers grew impatient with the delays.

Closings began in late 2009, more than two years after some buyers had signed their contracts.

And when purchasers did walk-throughs of the units, many felt they still weren’t complete enough to move into, said real estate attorney Debra Guzov, who represented a buyer at the project whose case has now been resolved.

“There were a whole group of people that were dissatisfied,” Guzov said. “It was basically an incomplete building. The developer was telling the outside world, ‘You can move in no problem,’ but really it was like walking onto a construction site.”

When closings began, roughly half of the buyers in contract tried to back out in various ways, according to multiple people familiar with the matter. Four went so far as to file lawsuits, and at least five applied to the AG for return of their deposits.

Others simply walked away, leaving all or most of their deposit on the table.

Neveloff said all of the lawsuits have since been settled but the terms of the agreements are being kept confidential.

Buyers at the building claimed that they were entitled to the return of their deposits for numerous reasons. They cited long delays, incomplete construction and their belief that the building didn’t measure up to what they’d been sold.

One purchaser stated that his living room was supposed to be 734 square feet, but was only 608 square feet. Several complained about cracking concrete and problems with the curtain wall.

“There were significant difficulties installing the curtain wall windows in the top floors of the building due to unforeseen wind complications, leading to the conclusion that the curtain wall leaks and does not work properly,” attorney Justin Bonnano wrote in the Barber complaint.

Buyers Babu and Susmita Jasty, both doctors practicing in Brooklyn, signed a contract in April 2007 to pay $2.175 million for unit 15B. By the time they were slated to close in November 2009, the building was “in no way, shape or form habitable,” they claimed in a lawsuit requesting the return of their deposit. The suit attributed these issues to the developers’ financial condition.

The sponsor “faced substantial financial problems during the course of construction, [and] because of such financial difficulties, did not construct the building as provided for in the offering plan,” the suit stated.

Another lawsuit was filed by the entity EAI Four. In that case, a buyer had signed a contract to purchase unit 8A for $4.05 million, and claimed the bedroom was missing a window.

One buyer (later reported to be the power couple of shipping heir Michael Recanati and his partner Ira Statfeld) in 2007 signed a contract to pay $24.48 million to combine eight units, creating a massive duplex on the building’s 17th and 18th floors. In an application to the AG for the return of their $4.9 million deposit, they claimed that the ceilings were 9’4″ high rather than the 11′ they were counting on to house their “extensive and valuable art collection.”

Another disgruntled purchaser was R. Martin Chavez, a partner at Goldman Sachs, who signed a contract in 2007 to purchase a $20 million penthouse on the 23rd floor, with private rooftop terrace. In April 2010, he filed an application with the AG for the return of his $3 million deposit, claiming the rooftop portion of the unit was inaccessible because of areas of incomplete flooring and excessive construction equipment, and the stairway leading to the roof had no lock, making it no longer private.

Chavez also claimed he should get his deposit back because his purchase was publicly disclosed in a newspaper article.

“The agreement provided for strict confidentiality,” his application stated, because his employer was “extremely concerned, especially in the current economic climate, that its executives do not publicize any lavish purchases.”

Lawyers for the sponsor vehemently denied the validity of these claims.

In one letter, Kramer Levin’s Jonathan Canter wrote to Chavez’s attorney: “The facts detailing purchaser’s dilatory and evasive maneuverings in this matter are self-evident. … Your letter brings vividly to mind the classic definition of chutzpah, i.e., the man who kills his parents and then asks for clemency on the grounds of being an orphan.”

In the end, some of the complainants ended up moving into their units, while others did not. The Jastys, for example, did not close, but Guzman closed on his unit in June for $3.6 million — about 7 percent less than the unit’s original asking price, according to StreetEasy.

Recanati and Statfeld did not close. Their unit was later purchased for roughly $20 million by Loren and JR Ridinger, cofounders of Internet marketing and product-brokerage firm Market America. Chavez did not close on his unit, and it is currently for sale for $22 million.

Post-crash remorse?

In response to these disputes, the sponsors’ attorneys argued that buyers simply wanted their money back because the market had cratered. The developers maintain that the building was built in accordance with the offering plan and any problems are cosmetic “punch list” items.

There’s little doubt that buyers’ remorse played a role at the Vision Machine. After the market tanked, buyers all over the city tried to get out of their contracts as property values declined. If values had continued shooting up, buyers would probably not have tried to back out of their contracts no matter how unhappy they were.

Moreover, some construction glitches are to be expected in any new building, especially one with a design as complex as this one.

“Obviously sometimes in new buildings, there are adjustments to make,” Ateliers Jean Nouvel’s Leininger said.

But current residents say they have legitimate reasons to be upset, beyond the usual construction hiccups. Similar complaints to those found in the initial round of lawsuits are now being voiced by current residents who have already closed on their units (many of whom got significant discounts from the original prices).

Some current residents complain that ceiling panels have fallen and appear to be held in place with masking tape, improperly poured concrete gives ceilings the appearance of water damage, and scars are visible on the terrazzo floors were walls were moved. One resident also said a window in the curtain wall never fully shuts, leaving a constant one-inch gap so the wind howls through the apartment.

Eberle, the photographer, said 40 Mercer is “built more solidly” than the Chelsea building. He has had leaks in the ceiling of his 100 Eleventh Avenue unit, but he’s more bothered by the rust on the steel beams he can see out his windows.

The rust is caused by transporting and installing the beams, and will be fixed when the weather warms up, said David Comfort, the project manager for Cape Advisors. As for the leak spotted by a reporter from The Real Deal in the lobby of the building, Comfort said it has since been fixed.

“We have not had any issues other than the normal punch list,” he said.

But not all buyers are unhappy.

Sunil Hirani, an investor and entrepreneur, purchased a 20th-floor unit in July 2010 and uses it as a pied-à-terre. “I love it,” he said. “The light, the design, everything, it’s great.

“Of course there were problems, as there would be in any new development,” he said, but added that if anything comes up, he feels confident that the developer will address it.

Another building resident, Roo Rogers, said he and his family “could not be happier.” The recent lobby alterations are “a change that I probably wouldn’t have made,” said Rogers, the son of acclaimed architect Richard Rogers, but he feels reaction to it has been “blown out of proportion.”

In a well-publicized incident this fall, the sales team attributed tepid sales to Nouvel’s stark lobby design, and hired Post to “soften” its appearance. Post (who says she is still owed money from the job, which the developers deny) added furniture and carpeting, and removed some of the elements Nouvel put in place, including a large box composed of reflective panels. The change outraged residents like Eberle, who felt the value of their investment was hurt by tinkering with Nouvel’s design.

Leininger said the changes were not discussed with the architect. “There was some modifications of the lobby design and these modifications were not approved by Jean Nouvel,” Leininger said.

He attributed complaints about the lobby’s appearance to the fact that Nouvel’s design was not yet complete when the changes were made, so the architect’s original vision was never fully realized.

Attorney Steven Einig, who represented a buyer in the building who applied to the AG for the return of a deposit, said starchitecture fuels high expectations for buyers.

“The big thing was that this building wasn’t a building, it was a piece of artwork,” said Einig, whose client’s case has been resolved. “There was so much emphasis on the design aspects of it … so any changes to that were very problematic.”

But the developers said the changes they made to Nouvel’s design were minor.

“There was one light that was not installed that was over near the concierge desk,” Comfort said. “I don’t think one light would have enough impact so as to change the feedback that we got.”

Residents say they are still very concerned about problems with the building, and more lawsuits are likely if the problems aren’t addressed.

“At some point there has to be some kind of resolution of these issues that I now know are faulty execution,” Eberle said. In a new construction building, some problems are always expected, he noted, “but it goes beyond question these things have to be resolved.”