The hot market for industrial properties in northern New Jersey continued apace in 2018 as the seemingly insatiable demands of e-commerce put a premium on warehouse and distribution facilities with last-mile delivery capabilities.

In 2018, about $2.6 billion in industrial property changed hands in the state. That was an increase of 24.3 percent over the average sales transaction volume in the three years prior, according to Colliers International. The commercial real estate firm found that in the fourth quarter, the average price for industrial space hit $126.67 per square foot — that’s 19 percent higher than the same time a year prior.

Although some observers said overdevelopment and geopolitical concerns could put a damper on the industrial market, most had enthusiastic outlooks for 2019.

“Industrial has never been as active as I’ve seen it in my 30-plus-year career,” said Jeffrey Heller, principal and managing director with Avison Young in Morristown. “Whether they’re old or new, distribution facilities are the most favored asset class.”

Driving much of the demand is the explosive growth of e-commerce, a retail sector that now accounts for 10 percent of consumer purchases in the country and one expected to grow to 13.7 percent by 2021, per consumer data firm Statista. With same-day or next-day delivery now the norm, last-mile distribution centers and close-in warehouses have become a critical link in the e-commerce supply chain.

Northern New Jersey’s proximity to New York City and central location between Boston and Washington, D.C., put it at the center of a major transportation corridor. The area’s significant population density and large pool of capable labor also serve to make it a key industrial locus.

“Infill markets are a huge driver for investors,” said Timothy Cadigan, a senior vice president at Avison Young in Morristown. “They are betting on location, location, location.”

Aided by the raising of the Bayonne Bridge in 2018 and continued deepening of the Kill Van Kull channel separating Bayonne and Staten Island, the amount of goods passing through the Port of New York and New Jersey — the busiest container port on the East Coast — increased nearly 87 percent between 2012 and 2017, according to import-export information provider Descartes Datamyne. Those improvements have allowed larger container ships carrying ever more goods destined for warehouses and distribution centers in northern New Jersey and elsewhere.

Bigger is better

For industrial real estate, geographic advantages are magnified. As manufacturing in the region dwindles and traditional retail and office real estate struggle to gain traction, investors of all types are homing in on industrial properties that are suitable for warehousing and distribution.

Commercial real estate veterans described an intense competition between local developers, international investors and, increasingly, institutional buyers to sink capital into sites in northern and central New Jersey.

“Every pension fund, advisor and [real estate investment trust], they all have allocations to invest in industrial in this marketplace,” said David Knee, an East Rutherford-based vice chairman of JLL’s Northeast industrial practice. “There’s a high cost of entry, but if you get in, you can see better rental rate growth than other tertiary markets.”

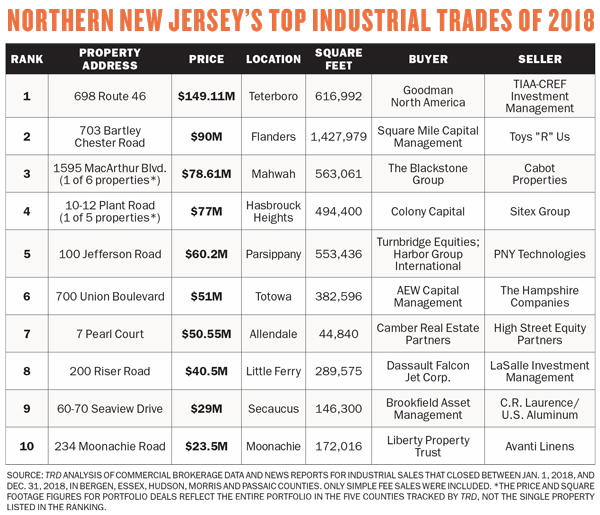

Colony Capital, a Los Angeles-based REIT, paid $77 million last summer to buy an industrial portfolio from the Sitex Group totaling 639,681 square feet in New Jersey, about 494,400 of which is in Hasbrouck Heights. In its announcement of the deal, which was the fourth-largest industrial trade in the region last year, according to The Real Deal’s analysis, Colony pointed to the site’s strategic location, its last-mile logistics capabilities and prospects for growth.

Burgeoning e-commerce sales and the warehouse logistical requirements of selecting, packing and getting the goods to consumers’ doorsteps often means that bigger is better when it comes to industrial properties.

Of the top 10 industrial sales in New Jersey last year, five were for buildings in excess of 200,000 square feet (the third- and fourth-largest sales were for portfolios of smaller industrial properties that collectively added up to more than 200,000 square feet). But size and a lack of supply remain obstacles in a region where the average industrial building is 50 years old.

“The biggest challenge in our state is sizable product,” said Thomas Monahan, a vice chairman of CBRE in Saddle Brook. “Tenants want larger buildings that are closer to population [centers].”

The scarcity of such properties is putting stress on the supply chain, especially in an environment where container ships can offload 20 to 30 percent more containers than before.

“A lot of the infrastructure at the terminal level, as well as trucking and warehouse capacity, can’t keep up with the growth,” added Adam Parish, who specializes in senior carrier management and procurement at freight forwarder Flexport.

That issue is helping drive prices northward.

“Most transactions that we’re handling these days are noteworthy because of the metrics they’re selling for,” said H. Gary Gabriel, an East Rutherford-based vice chair of Cushman & Wakefield’s Metropolitan Area Capital Markets Group. “When you’re selling industrial buildings on average for more than you’re selling office buildings for, that raises eyebrows.”

Cushman brokered the sale last summer of a 616,992-square-foot Amazon fulfillment center in Teterboro that set a New Jersey industrial sales record and ranks at the top of TRD’s list of priciest industrial sales. In its announcement of the deal, the buyer, Australia’s Goodman Group, said the property was one of only two Class A logistics centers in northern New Jersey. Located just a short drive from the George Washington Bridge and boasting a premier tenant in the e-commerce titan, the site was sold for $149.11 million by teachers’ pension fund TIAA-CREF, which according to real estate analytics company CoStar Group paid just over half of that sum —$81 million — for the property in 2013.

“It’s a large piece of property and a large building ideally located with the right tenant and installation,” said Gabriel, adding that Amazon had made significant investments in the fulfillment center. “Investors got quite enthusiastic about the opportunity.”

Industrial essentials

In the sixth-largest industrial trade of the year, the Hampshire Companies of Morristown sold a 382,596-square-foot building in Totowa last November to real estate investor AEW Capital Management of Boston for $51 million. It was reportedly two and a half times what the seller paid for the property two years earlier.

Part of the former manufacturing facility had been enlarged and retrofitted for warehouse and distribution, with 52 loading doors, an essential feature for same-day delivery.

“It’s an investment,” said HFF’s Florham Park-based senior managing director and co-head of capital markets, Jose Cruz, when asked about AEW’s purchase. “They look at northern New Jersey as a growth market.”

In some cases, scarcity is driving conversions of obsolete manufacturing centers and other types of facilities for warehouse and distribution purposes. Essential these days are heavy-duty electrical power, super-flat floors for the movement of equipment and high ceilings for racking merchandise, as well as plentiful loading bays for trucks and parking for the hundreds of employees who receive goods and get them out the door to consumers. And while landlords have yet to charge tenants for cubic feet, some brokers believe that day is coming.

New development is also making up for a dearth of available industrial properties. In northern and central New Jersey, there are currently 28 industrial buildings under construction, according to Colliers, with 40.8 percent of the still-in-process space already preleased.

“Land prices have exploded,” said Cushman’s Gabriel. “There is so much capital looking for existing buildings that they can’t find. What most institutional investors and developers are doing today is if they can’t buy it, they build it.”

The Rockefeller Group, for example, paid $57 million in 2017 for a 228-acre site in Piscataway that once housed a Dow Chemical plastics factory. Rockefeller is now putting up five buildings there to use as distribution centers. It purchased the site from Lincoln Equities Group (LEG), which bought the property for $13 million in 2014.

Investors are also bidding up smaller sites, such as a 4.5-acre parcel at 120 Frontage Road near Newark Liberty International Airport that sold in October for $8.2 million, or more than $100 per square foot. There were three rounds of bidding by some of the largest industrial buyers in the U.S., including a REIT and a private equity fund, said HFF’s Cruz, who brokered the deal.

Investors are also bidding up smaller sites, such as a 4.5-acre parcel at 120 Frontage Road near Newark Liberty International Airport that sold in October for $8.2 million, or more than $100 per square foot. There were three rounds of bidding by some of the largest industrial buyers in the U.S., including a REIT and a private equity fund, said HFF’s Cruz, who brokered the deal.

“For Newark, it’s among the highest prices we’ve seen,” Cruz said.

A mere 5.67-acre development site near the Meadowlands sold for $8 million to the Blackstone Group in January. The buyout giant plans to build an 85,000-square-foot warehouse and distribution center on the site. Last summer, LEG also bought the 90-acre former Military Ocean Terminal in Bayonne, where the firm plans to build out 1.6 million square feet of warehouse space for a logistics center.

LEG President Joel Bergstein cited the property’s “prime location” on New York Harbor and close to other transit routes as the impetus for its purchase. LEG itself used to be primarily an office and residential developer, but Bergstein saw the “market begin to change” five years ago.

“We saw vacancies in industrial buildings and a sustained, predictable increase in e-commerce business in containers coming into the port,” he said. “We were a little ahead of the curve.”

How long industrial properties in northern New Jersey will remain in demand is uncertain. Local real estate veterans remain optimistic about the sector’s outlook, citing a strong pipeline of investors lining up for potential purchases.

In the meantime, scarce inventory in the region is sending some buyers and developers farther south on I-95 into Middlesex County, where Clarion Partners bought a 1.24 million-square-foot distribution facility in Cranbury for $150 million in 2017. At the end of 2018, there were 5.4 million square feet of rentable building area under construction in northern New Jersey, according to Colliers, and almost as much, 4.9 million square feet, in central New Jersey.

Some market experts predict that the industrial action will soon move into New York City’s outer boroughs.

“Northern New Jersey is not going away,” said Robert Kossar, an East Rutherford-based vice chairman of JLL’s Northeast industrial region. “But you’re going to see new, modern fulfillment and distribution space in every Industrial Business Zone in the city [in order] to successfully service the local market — not with a million square feet in New Jersey or Long Island.”

Even so, New Jersey’s industrial market is off to a hot start in 2019, with at least 17 properties trading in the northern and central counties of the state, according to news reports.

“It’s tough to find a dark cloud on the horizon for industrial,” said HFF’s Cruz.