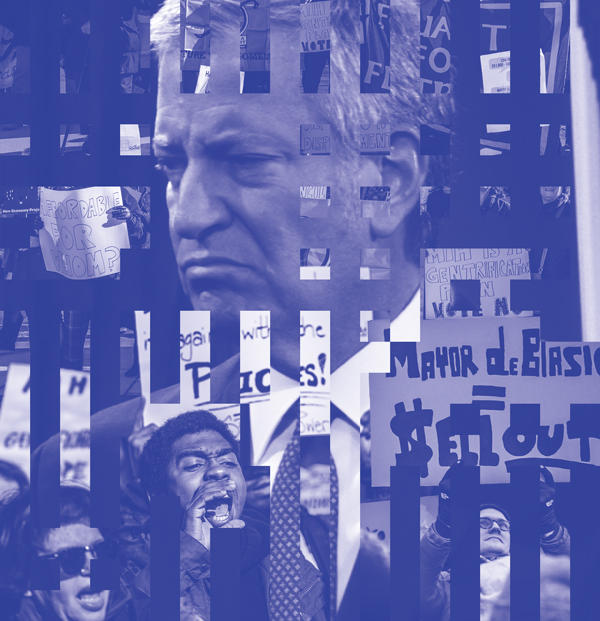

Five months into his mayoralty, Bill de Blasio blasted out a press release that quoted 80 elected officials, developers and advocates praising his new $41 billion housing plan. He’s been taking victory laps ever since to celebrate its progress.

Five months into his mayoralty, Bill de Blasio blasted out a press release that quoted 80 elected officials, developers and advocates praising his new $41 billion housing plan. He’s been taking victory laps ever since to celebrate its progress.

But Vicki Been, his deputy mayor for housing and economic development, acknowledged last fall that some New Yorkers aren’t buying it. In fact, many have come to believe that the hundreds of thousands of new apartments de Blasio vowed would keep their rents down will instead drive them up.

“We’ve lost the narrative,” Been lamented at an October forum. “We’ve lost the hearts and minds of neighborhoods in the sense that they are worried about being pushed out when they see affordable housing that is not affordable to them or to their neighbors.”

Her words proved prescient. The mayor’s housing plans have suffered a string of setbacks in the past two months, as three sweeping rezonings hit roadblocks and a major apartment project in Queens was shelved.

The task of reclaiming the narrative — and salvaging the mayor’s housing legacy — is now in the hands of a team he tapped just last year following Alicia Glen’s departure. Led by Been, it also includes new heads at the Department of Buildings, Department of Housing Preservation and Development and New York City Housing Authority.

“Throughout the administration we’ve been raising the bar to do more and more and more,” Been told The Real Deal, downplaying the idea of a new urgency. “That pressure has always been there.”

But now it’s greater than ever, as losses continue to pile up halfway through de Blasio’s final term — especially when it comes to his signature Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program, which depends on rezonings. Key City Council members last month came out against big rezonings planned for Bushwick and the South Bronx on the heels of a judge in December annulling the mayor’s rezoning of Inwood.

That leaves de Blasio with less than two years to rezone nine of the 15 neighborhoods his administration has targeted.

Of course, the mayor has made significant strides toward his goal of creating or preserving 300,000 affordable units by 2026 (up from his original target of 200,000 by 2024). Administration officials say they are on pace with 137,000 affordable housing units created or preserved since 2014. At the same time, criticism is mounting about the levels of affordability offered in these projects and their perceived effect of increasing area rents.

“It’s difficult for us to believe the administration or City Planning when they say, ‘We’re not going to displace the community,’ when they aren’t studying it,” Bronx Council member Rafael Salamanca said in an interview. Last month he declared his opposition to the rezoning of 130 blocks in his district, effectively killing it before the public approval process could even begin.

Developers are increasingly looking to affordable housing as a profitable alternative to markets that are lagging, such as luxury residential. But such projects require heavy subsidies, and the city and state’s resources are strained. Just as daunting are the political obstacles, as advocates continue to argue that the administration is placing too much emphasis on the volume of apartments and not enough on affordability by the city’s most vulnerable.

“I think that the legacy as it stands now is a really mixed bag,” said Emily Goldstein, director of organizing and advocacy at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development.

“There have been huge leaps forward,” she explained. “On the flipside, this mayor’s housing plan is actually remarkably similar to [those of] previous administrations. It focuses so much on a unit count and loses sight of some of the things that matter more.”

“There have been huge leaps forward,” she explained. “On the flipside, this mayor’s housing plan is actually remarkably similar to [those of] previous administrations. It focuses so much on a unit count and loses sight of some of the things that matter more.”

The high cost of low rents

The City Council approved de Blasio’s MIH program in March 2016, implementing affordability requirements that he hoped would be welcomed by communities otherwise resistant to development.

The program, a cornerstone of the mayor’s housing plan, requires developers to set aside affordable units when they build in neighborhoods rezoned to allow larger projects. Its structure of income tiers was designed to make projects profitable as well as socially diverse, rather than concentrating poverty as past housing programs had.

“Years from now, when working-class families and seniors are living soundly in their homes without fear of being priced out, we will look back on this as a pivotal moment when we turned the tide to keep our city a place for ALL New Yorkers,” de Blasio said in a statement at the time.

However, critics from both sides of the political spectrum have questioned the program’s efficacy. Conservatives lament that it hasn’t produced much affordable housing construction without significant subsidies.

Just over 2,000 MIH units were permitted or constructed from the start of the program through September 2019, according to an analysis by the Manhattan Institute, a think tank that advocates for free markets. In about twice as much time, more than 8,400 affordable units under previous mayors’ voluntary inclusionary housing plans have been approved since de Blasio took office. Those projects were eligible for tax exemptions but didn’t receive other subsidies, the study noted.

Goldstein faulted the de Blasio administration for having only rezoned low-income communities of color, such as East Harlem and East New York.

And while voices on the left claim that poor communities have been targeted — portraying the mayor’s ballyhooed rezonings as a burden — the Manhattan Institute’s report points to the effect of wealthy ones being spared: The administration has yet to rezone a housing market that can support MIH’s affordability requirements without public subsidy.

But it has done so for individual sites. The report’s author, former city planner Eric Kober, pointed to one in West Chelsea as a rare example of the program succeeding.

Douglaston Development is building two rental towers at 601 West 29th Street with 25 percent of the 931 units pegged as affordable. There is no subsidy beyond a tax abatement unrelated to MIH, according to its developer. In a weaker housing market, such as Downtown Far Rockaway, that would not be possible.

“When you are building in emerging areas, the market rents in these areas are not the market rents that you would experience in Manhattan or the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront,” said Douglaston’s chairman, Jeff Levine. “You’re in a tough place.”

The mayor’s office picked the first neighborhoods to rezone in part because the local City Council members were open to the idea (lawmakers customarily fall in line with the member whose district is affected). City planners are thus loath to commence the long, arduous rezoning process without a clear path to approval. The public review alone takes seven months and must be preceded by extensive preparation and environmental studies.

During a Jan. 24 appearance on the Brian Lehrer Show, de Blasio said in his time left as mayor, he wants to continue to focus on rezoning efforts where there is support at the outset.

“Do we need more affordable housing in areas that are privileged? … Of course, the answer is yes,” de Blasio said. “We have to be honest. We fought these battles in brownstone Brooklyn. If you lock in place a privileged community, you are on that pathway to San Francisco.”

The mayor often cites the California city to argue that if growth is not accommodated, demand for housing will send prices skyrocketing and push the non-wealthy to distant neighborhoods.

But even in poor and working-class communities, opposition to his plans has been significant. The mayor’s office has had to make concessions and promise substantial city funding to secure the necessary political support for the rezonings accomplished to date. And in Inwood, local opponents sued anyway — and were pleasantly surprised when a judge ruled that the city didn’t adequately examine the rezoning’s potential socioeconomic impacts. The administration is appealing.

“The MIH program has a ton of potential, but the devil is in the details,” said Michael Tortorici, a founding member of the commercial brokerage Ariel Property Advisors. “It’s a delicate balance between the goals of the administration and what the local communities allow.”

The administration’s plan to rezone Bushwick suffered a potentially fatal blow last month as the local Council members, Antonio Reynoso and Rafael Espinal, backed a highly restrictive alternative proposed by community groups. (Espinal, who has since resigned to run the Freelancers Union, had carried the mayor’s initial rezoning, in East New York, across the finish line despite some local opposition.) And the city’s South Bronx rezoning was pre-emptively killed by Salamanca, who argued it would gentrify his district.

Salamanca, who chairs the City Council’s powerful land use committee, is backing a bill proposed by Public Advocate Jumaane Williams that would mandate racial-impact studies for land-use actions requiring an environmental review.

Neighborhood-wide rezonings allow developers to build larger projects without the added cost and uncertainty of negotiating for the local Council member’s approval. But Salamanca said he is better off working with developers on a project-by-project basis so that he can push for deeper levels of affordability.

As the mayor coped with the rezoning troubles, the Durst Organization shelved its seven-building, 2,000-unit Halletts Point rental project in Astoria that was set to include hundreds of affordable apartments. The developer contends that the mayor insisted on terms that made it uneconomical.

“A project as large and complex as Halletts Point requires a partnership between the developer and the city,” Durst spokesperson Jordan Barowitz told Politico. “Unfortunately, we have never been able to forge this partnership, and without it, the project is impossible to build.”

Hard numbers game

Hard numbers game

Tax exemptions and abatements play a major role in the mayor’s affordable housing agenda.

The city gave up $2.3 billion in residential property taxes in fiscal year 2019, according to the city’s Department of Finance, although not all of that was tied to affordability. The old 421a program granted tax breaks lasting up to 25 years to new apartment projects, but only in the city’s pricier neighborhoods did it require some units to be affordable.

The new version of 421a, dubbed Affordable New York, only grants the exemption if a certain portion of a project is affordable. Other tax breaks adhere to that same principle.

In June, a joint venture between Camber Property Group and Belveron Partners bought a 400-unit apartment building called Highbridge House from Stellar Management for $76.3 million. The partners re-regulated rents for the property’s 400 units to get a 40-year tax exemption through a program known as Article XI. (The deal closed just after the state passed a rent law that made it nearly impossible for landlords to deregulate apartments.)

Camber’s Rick Gropper said he expects more developers to turn to affordable housing construction as New York’s luxury residential market continues to slow. “There’s more demand than ever for city resources for affordable housing,” he said.

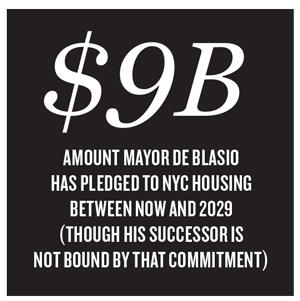

De Blasio knew from the beginning that ample public funds would be needed to build affordable housing at scale in weaker markets. He allocated $5.9 billion through September 2019 and has pledged more than $9 billion between now and 2029, although his successor is not bound by that commitment.

Alan Wiener, head of Wells Fargo Multifamily Capital, said de Blasio’s successor must dedicate significant public resources to meet the city’s ballooning housing needs. But the longtime banker also praised de Blasio for his housing record.

“I think it’s actually one of his crowning achievements,” Wiener said. “They’ve made it and kept it as a priority.”

City officials have become more deliberate, however, in doling out housing dollars.

“For a while it was gangbusters, and then it was, ‘Whoop, we don’t have any money,’” said Lisa Gomez, chief operating officer and partner at affordable housing builder L+M Development. “There’s finite resources even in a city like New York. There’s a very long queue for financing.”

Been, who previously served as de Blasio’s HPD commissioner before leaving in early 2017 for a 28-month stint in academia, said there has been no decline in capital financing. But she said the administration has worked to be more transparent about the federal cap on tax-exempt bonds, which finance tens of thousands of affordable units across the state each year.

The wait for financing isn’t the only bureaucratic hurdle for affordable housing developers. Real estate attorney Alvin Schein said there is “little coordination between HPD and DOB” on aspects of the building process.

One issue Schein has encountered is securing a waiver from the buildings department to include less parking than normally required with a development, as permitted for projects near mass transit under a measure approved in 2016 called Zoning for Quality and Affordability. The agency sometimes declines to issue a waiver without documentation that a project includes affordable housing.

But Schein said Affordable New York developments don’t receive such documentation until after construction is complete. “In most cases it just slows down the project [and] makes the project more expensive,” he said. “The mindset should be, ‘Let’s get affordable housing out in the market as fast as we can.’”

A representative for HPD denied any lack of coordination, noting that projects are presented to the two agencies at different times.

Housing for the poorest

A perennial criticism of de Blasio’s housing plan is that it doesn’t help enough of the city’s lowest-income residents.

In a 2018 report, City Comptroller Scott Stringer called on the administration to redirect housing funding to severely rent-burdened New Yorkers, noting that the average city household with income between $10,000 and $20,000 spent 74 percent of that on housing.

Meanwhile, the city’s homeless shelter population, although it has edged down 1 percent in the past year, is still nearly 60,000, about 18 percent higher than when de Blasio was sworn in.

Last month, Stringer — who is running for mayor — criticized the MIH program, saying it has failed to create enough deeply affordable units and has “cherry-picked” communities for rezonings that exacerbated speculative buying.

“In the name of development and in the name of growth, we’re leaving far, far too many of our people behind,” the comptroller said. “The status quo is nothing less than taxpayer-funded gentrification.”

The latest data from the de Blasio administration shows it has created or preserved about 23,500 units for tenants who make 30 percent or less of the area median income. Its most robust tier has been for those making 51 percent to 80 percent of AMI: more than 57,000 apartments.

The administration often notes that housing for very low-income tenants requires a lot of subsidy, reducing the number of units that can be built for working-class and middle-class households. That’s important because middle-income earners who don’t win lotteries for subsidized units then outcompete lower earners for other housing, pushing many into living doubled-up or homelessness, the mayor’s housing officials say.

But their argument that adding housing at all levels indirectly helps low earners has not resonated. And while the mayor talks of the benefits to the poor of living in economically diverse areas, community activists characterize it as gentrification that forces minorities to leave their neighborhoods.

“Many people believe you can ask for more [affordability in private projects]. You can ask for more, but they are not the ones looking at the data, the spreadsheets, the pro formas every day,” Been said. “At the end of the day, you push too hard, you get absolutely nothing.” (The Durst Organization said its Astoria project is case in point.)

But the deputy mayor acknowledged that the messaging about unit count has not won over New Yorkers.

“I don’t think people relate all that well to just numbers,” Been noted. “We need to be telling people a lot more about the actual people who are being helped.”

Shifting gears

Over his tenure, the mayor has turned more of his attention to very low-income and homeless New Yorkers.

Late last year he compromised on a City Council bill that aimed to reserve more housing for people emerging from homelessness. The bill, which passed in December, requires city-funded projects of 41 units or more to set aside 15 percent of them for homeless individuals.

De Blasio had opposed an earlier version that applied to all city-funded projects, arguing that it would make some unviable. Before that, in February 2017, the mayor had dedicated $1.9 billion to set aside another 10,000 apartments for New Yorkers earning less than $40,000.

In December 2018, the mayor launched NYCHA 2.0, a 10-year plan to help address what is now $40 billion in capital repairs needed by the city’s public housing.

While the administration is privatizing the management of many of the Housing Authority’s properties to pay for renovations, its plan to allow private development on underutilized land and to sell development rights to raise $2 billion has been stalled by opposition from tenants.

The Bloomberg administration had the same idea and ran into the same problem. To date, not a single private housing development on NYCHA land has been approved.

De Blasio will not be cutting ribbons on any such projects before leaving office in 23 months. Nor can he expect to finish nine more neighborhood rezonings. Meanwhile, the developers who were counting on de Blasio’s housing plan may have to rely on his successor to finish the job.

But it remains to be seen how much the mayor can build on the efforts of his first six years and what that will ultimately mean for his legacy.

“I think that the administration has made a lot of strides,” Tortorici said. “The seeds that they plant today will take a long time to come to fruition.”