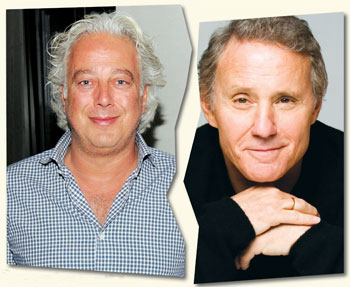

From left: Aby Rosen and Ian Schrager

Now that their split is official, financier Aby Rosen and hotel impresario Ian Schrager are wasting little time moving on.

Rosen acknowledged publicly for the first time last month that he had reached a deal to buy his ex-partner out of the Gramercy Park Hotel, the troubled boutique project the pair sank $200 million into renovating during the frothy pre-crash days. Then he issued a news release touting the new additions he has planned on his own for the 185-room high-end hotel, including a redesigned culinary operation headed by famed restaurateur and Shake Shack founder Danny Meyer.

Schrager, meanwhile, is actively searching for the site of his “next big thing” and is “in the early stages” of evaluating a hotel within 10 blocks of the Gramercy, said one industry source who asked to remain anonymous. Schrager’s next New York hotel is expected to be developed in collaboration with his partners at Marriott, which is rolling out a new line of boutique hotels called Edition.

“It’s a hotel that’s not publicly announced for sale,” said the source. “He’s giving it a pretty hard look. They’ve run some preliminary analysis as to renovation fees.”

Meanwhile, Schrager’s team followed Rosen’s news with an announcement of its own, confirming the split, and noting that “the [Gramercy] sale comes as no surprise to those who are familiar with Schrager, whose real passion lies in creating new things, new experiences, new companies and challenging the status quo.”

“It was a very good financial transaction for me,” Schrager said in a news release. “I received an offer that was just too good to refuse.”

The release noted that along with Marriott’s Edition, Schrager would focus on creating another new hotel brand through a private hotel company called Schrager Hotels.

Both Schrager and Rosen declined to comment for this article. But one source said Rosen and his company, RFR, had agreed to pay Schrager “somewhere around $20 million” — which is substantially less than the value of his stake prior to the credit crash.

As has been widely reported, the duo defaulted in July on a $140 million loan from Union Labor Life Insurance. The mortgage lender was reportedly offering the loan at a 10 percent discount as recently as November, and Rosen has been negotiating to buy back the debt. RFR, through a spokesperson, said, “A deal has been completed regarding the debt so there is no default at this time, but terms remain confidential.”

Those familiar with the Rosen-Schrager split, which was first reported in the New York Post this fall, speculated that Schrager either couldn’t raise the cash to “double down” on the project, or simply wanted to move on to new things after putting his imprint on the brand. Rosen, on the other hand, has been actively buying back and reshuffling his debt on a variety of properties in recent months.

Many said that the unraveling of the pair’s partnership was only a matter of time. The debt load on the Gramercy Park Hotel left little room for error, said Dan Fasulo, managing director of Real Capital Analytics.

“Their cost basis was extremely high, which basically gives you little wiggle room if room rates and occupancy levels fall, as they have in the recent downturn,” he said. “They spent a tremendous amount of money on the renovation repositioning that property.”

Financial motivations aside, big egos were also a key factor in the split.

“It was no surprise at all that it didn’t work out,” said one industry player who knows them both. “They are both difficult guys. With both of them, it’s gotta be ‘my way.'”

Rosen admitted in an interview with the New York Times last month that it was “definitely the case” that egos played a role in the split.

“We made a lot of money together, but we had differences,” the paper quoted him saying. “Ian is pursuing a different career right now — he’s doing a lot of work for Marriott.”

Indeed, part of the tension, one industry source said, was Schrager’s alliance with Marriott, which was announced in 2007. Schrager’s subsequent collaboration added to his differences with Rosen, the source said, noting that the relationship is “less comfortable now that Ian also has a relationship with Marriott.”

Still, Rosen denied there was any lingering animosity. “We’re very much friends,” he told the Times. “I just had lunch with him.”

A number of industry analysts said Rosen’s ability to reach an agreement with his lenders was no surprise.

Fasulo noted that property owners can create a lot of legal roadblocks, headaches and delays for any financial institution attempting to foreclose. And, many industry analysts said, as the owner Rosen had the clear edge over outside buyers on purchasing back the debt all along.

“It’s not unusual if you have the money to do it,” Fasulo said. “But I think it’s very much limited to the best markets, especially the supply-constrained markets like Manhattan. But these deals don’t necessarily get out into the public until way after, because these are private transactions.”

Banks have an incentive to sell the debt back to the owner, he added, because “it’s a pretty painless process for the bank to work with the owner as long as they feel they are getting close to market value. Why not? An owner can give you a really hard time. When a property is in default, all a bank cares about is getting a big check to get out of the situation; they don’t care who the check comes from at the end of the day.”

Sean Hennessey — founder and CEO of Lodging Investment Advisors, a Manhattan-based hotel investment advisory firm — said Rosen’s lenders would have had an incentive to sell once the value of their distressed loan had risen to 85 to 90 percent of face value.

“The value of the loan, less the cost of any litigation and the cost of taking the property by force, is the basis for pricing a note sale,” he said. “If you can market a loan for 85 percent to 90 percent of face value, that makes it a lot more of an attractive option.”

It’s unclear whether the duo’s loan went into default because it came due and there was no refinancing available or whether the property’s earnings simply sank to a level insufficient to service the debt. Whatever the case, the default would certainly “jump-start discussions” between the borrowing entity and the lender to resolve the issue,” said Hennessey.

At that point, “Rosen could go to the lender and say, ‘Ian wants out. I want to step up and make this right. Let’s make a deal.'”

Hennessey said he expects to see a flood of New York City hotel deals in the coming months — including those in which buyers snap up existing defaulted debt that owners are unable to buy back themselves.

A better market has finally created the conditions necessary to get things rolling.

For one, average revenue per room, or Revpar, has rebounded from a low of $165.57 to a 12-month average of $186.54 — though it’s still far below the precrash levels of $235.97.

Occupancy rates, meanwhile, are approaching the highest levels ever recorded. New York City’s 12-month occupancy average has risen from a low point of 75.9 percent to 80.2 percent. The highest levels ever recorded in the city are 83.8 percent.

“Because the recovery is further along in New York, and because there are so many investors eager to spend capital, there is an incredible built-up demand in New York,” Hennessey said. “Buyers are not ascribing a huge discount to the current weakness in earnings; most of them feel that will be overcome in short order.”

“There are a lot of people getting ready to go to market now [with debt and properties],” he said. “And it will be a very active market over the next 24 months.”

Rosen has been especially active already. The Gramercy loan is not the first loan he’s bought back after defaulting. According to published reports, he did the same at 66 East 55th Street late last year. And he told the Times that RFR had “reshuffled all our debt.”

“We bought some back, refinanced it, and pushed up maturity dates to 2015, 2016 — and there’s not one piece of debt that went back to the lenders,” he was quoted as saying. “We bought back and reshuffled over $3.5 billion worth of notes. Ninety-nine percent of our headaches are gone.”

Including, as of last month, Schrager.

“It’s sometimes hard to get along well when you’re doing well and you have to split up a pie. You take two guys who have big egos and a deal that’s gone bad, and it’s not going to end well,” said one anonymous source.