When the real estate market crashed, tales of lowball offers abounded in New York: Buyers were in many cases demanding discounts of 25, even 30 percent, off asking prices. Those days, relieved brokers say, have passed.

But in this steadier-if-somewhat-

uncertain market, some say another frustration has emerged. Sellers, emboldened by the market’s relative improvement in the last year, are now the ones pushing

their luck.

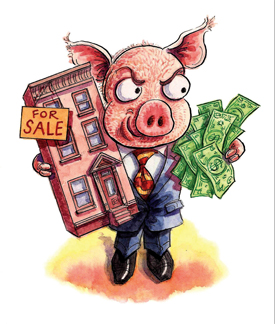

While brokers and analysts agree that the market is still fragile, they say some sellers are getting greedy and demanding prices higher than currently justified.

To rationalize those higher prices, they are pointing to the recent bounce in sales activity and rejecting comps they

feel are too low.

“In the current climate, sellers are not asking; sellers are demanding,” said Patricia Levan, president of Levan Real Estate in Manhattan. “Some sellers are demanding unrealistic prices, and they will find an agent to support that fantasy.”

Levan recently parted ways with a client who was selling a condo unit at 212 East 47th Street. The apartment — which was originally listed at $765,000 and later reduced to $745,000 — had no offers. The problem, Levan said, was that an apartment on the same line (but a few floors up, and renovated) had sold for $675,000 in the fall. The seller, however, wrote off that lower comparable as the product of a bygone weak market and refused to lower the price further. Eventually, the seller pulled the unit off the market.

The case, Levan said, illustrates that the market is in a new, tenuous place. More sellers are rejecting sales comps from the downturn because they believe they can find buyers to pay more.

“I don’t think sellers realize how closely tied they are to what’s sold in their building,” she said. “That comp is really never going to go away. Maybe in a really, really good market it’ll be more overlooked, but right now, it’s not.”

While not all sellers are digging their heels in, the ones that are, Levan said, have created something of a slowdown in the market and are making it harder to get deals done.

The experts, meanwhile, are not quite as optimistic as the sellers.

Jonathan Miller, president and CEO of the appraisal and consulting firm Miller Samuel, refused to even use the word “recovery” to describe the current market.

“It’s a consistent, stable market — not a booming market — certainly far better than it was a couple years ago, and the word for that is ‘rebound,’ not ‘recovery,'” Miller said, adding, “When I hear the word ‘recovery,’ to me it implies that we’ve recovered, and the market’s going to go up now, and I contend that we don’t really know.”

Miller said, however, that conditions exist to make some sellers less flexible.

The volume of sales has generally been trending upward, he said, with an unusual spike in activity in March and another upswing more recently. That, he noted, is consistent with spring’s status as “the Super Bowl of the annual housing market.”

But coming off the last few dismal years, the back-to-normal seasonal bounce has resulted in stronger seller optimism and a belief — whether true or not — that the market is in recovery mode.

“You do see sellers who see an increase in demand and think that they can be a little bit tougher, a little bit less negotiable,” he said.

Emma Hamilton Malina, a senior associate broker at the Corcoran Group, said she is seeing overpriced properties hit the market and fall flat. Often, she said, that’s a result of sellers or their brokers setting a high asking price “to allow room

for negotiations.”

But she said that such a strategy can backfire if the high price causes the listing to sit for too long and get stale. Price cuts at that point can send the message that the property is flawed or the seller is desperate, leading to even

lower offers.

Jeff Stockwell, a senior vice president at Stribling and Associates, said because sellers see some improvement in the market they are rejecting perfectly good offers and demanding higher prices.

He recalled two recent listings in which his price assessments, and those of his sellers, were far apart.

One listing, an 11,000-square-foot, industrial Clinton Hill building with a residential component, was appraised 18 months ago. Last fall, a buyer was willing to pay more than the appraised value and had even signed a contract. But the seller backed out and then turned down an offer this spring for twice the appraised value. The building is now off the market and Stockwell is marketing the ground-floor commercial space as a rental.

Both buyers remain interested, he said, but his seller does not want to sell at the current market prices.

“Her thought was that values in rural Asia were more than $200 a foot, and she didn’t understand why she couldn’t get a lot more in Brooklyn,” Stockwell said.

In another case, a client selling a 2,000-square-foot loft in Tribeca rejected a deal to sell the apartment for significantly more than four recent comps in the building. The seller, who in the end decided to rent the unit out, believes its resale value will rise by 50 percent over the next five years, Stockwell said.

“And these are very smart people making these choices,” he said. “It really highlights that there’s no true consensus on where the market’s going, and maybe that’s because there’s no true consensus on where the economy’s going.”

Miller dismissed the idea that seller inflexibility could slow the market’s recovery.

“For that to happen, there would have to be a significant disconnect between sellers and reality, and I’m not sure what would drive that,” he said, noting that macroeconomic news, in recent months, has been downbeat.

Still, Stockwell said, there are plenty of potentially negative consequences on an individual level.

“I’m not trying to say the market’s not good,” he said. “But it’s not a market in which you should get greedy, because you might regret it later.”