It was early January — just weeks after President Trump’s tax bill went into effect — when Colby Gaines, a producer of the reality TV show “Pawn Stars,” approached his wife with a radical idea. The couple, he said, should move from New Jersey back to his native Texas, where they could save $500,000 a year on taxes.

“It was just so stark,” said the founder of Back Roads Entertainment. “It’s undeniable to anyone who understands basic economics.”

In May, the couple paid just over $4 million for a Spanish-style house in an upscale neighborhood in Austin, and listed their custom-built home in Westfield, New Jersey, for $6.95 million. The movers are scheduled for August.

After years of wooing businesses and wealthy residents, states like Texas and Florida are having a moment: The promise of warm weather, zero state income tax and relatively low property taxes is drawing a wave of Wall Street investors, real estate executives and other wealthy residents from New York and the tri-state area.

The boost for these states can be traced back to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which was enacted in December. While taxpayers were previously allowed to write off all of their property taxes by deducting the lion’s share of their state and local taxes from their federal tax bill, those so-called SALT deductions are now capped at just $10,000.

While the Trump administration has touted the tax reform package as a way to spur job growth, those who live in areas with high property taxes (and many of the elected officials who represent them) feel otherwise.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has said the cap on the SALT deduction would “destroy” New York, which has one of the highest property tax rates in the country.

In all, some 8.3 percent of taxpayers in New York are bracing for a tax hike, according to an analysis by the nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based think tank the Tax Policy Center. Ten percent of New Jersey taxpayers — who already pay the highest property taxes in the U.S. — can expect to see their bills rise, followed by Maryland and Washington, D.C. (with 9.4 percent of homeowners seeing a tax jump) and California (with 8.6 percent).

And for some, moving to a lower-tax state makes the most financial sense.

Corcoran CEO Pam Liebman told the Wall Street Journal last month that she was aware of 15 buyers in the New York area doing just that. “Wherever they live they are putting their properties on the market,” she told the publication.

Corcoran CEO Pam Liebman told the Wall Street Journal last month that she was aware of 15 buyers in the New York area doing just that. “Wherever they live they are putting their properties on the market,” she told the publication.

Douglas Elliman’s Richard Steinberg, a licensed agent in New York and Florida, noted that there is good reason for these relocations. “You can save a million [dollars] a year,” he said. “That’s real money.”

New Yorkers no more

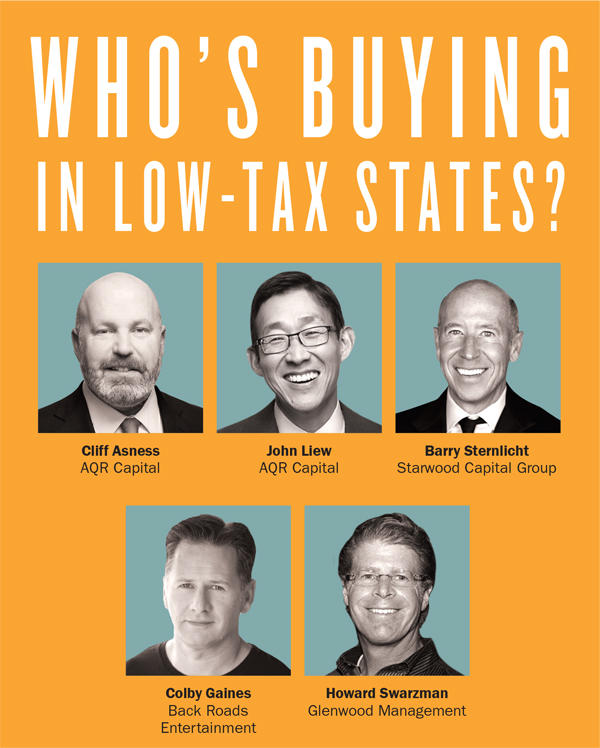

For years, real estate bigwigs like Howard Lorber, Kevin Maloney and Barry Sternlicht have worked (and played) in Miami.

Maloney, founder of Property Markets Group, has been known to fly himself to and from Miami, where he spends half the week. Meanwhile, Lorber’s Vector Group — Elliman’s parent company — is headquartered in Miami, and the brokerage chief owns several properties in the Sunshine State.

Lorber, a long-time Trump friend and backer, declined to comment for this article, but he’s previously predicted that “the city will not have a mass exodus” as a result of changes to the SALT deduction.

But for some — like Sternlicht, asset manager Eddie Lampert and hedge funder Paul Tudor Jones — the migration began three years ago, when Connecticut enacted sweeping changes to its tax code that impacted financial firms.

In 2016, after paying $17 million for a waterfront property in Miami Beach, Sternlicht officially became a Florida resident. His Starwood Capital Group — which moved its headquarters to Stamford, Connecticut, from Westchester in 2012 — in April designated Miami as its mothership. The company is keeping an office in Greenwich but is currently developing a new headquarters in Florida, set to open in 2021. (Sternlicht still appears to own a sprawling Greenwich estate, which he bought in 2005, according to public records.)

“You can’t give away a house in Greenwich,” Sternlicht said in 2016, referring to the tony enclave that’s home to major financial firms and their executives. “We got too close to the Manhattan tax rates.”

While the new federal tax policy actually favors the wealthy and corporations — the top corporate tax rate will sink to 21 percent from 35 percent, the alternative minimum tax (AMT) will hit far fewer people, and the estate tax exemption doubled — those living in high-property-tax states will see much of the personal relief they get offset by the new SALT cap.

In mid-June, Elliman’s Oren Alexander said the Miami market had more action in the prior 45 days than it did in the previous two years. “I think the amount of activity we’ve seen is also just beginning,” he said.

His theory is that in April, when everyone cut 2017 tax checks to the IRS, they realized how much money they could save by living in Florida.

And while there is not a widespread exodus of New Yorkers fleeing the area, those calculations have translated into action — at least for some.

I Squared Capital’s Sadek Wahba and Adil Rahmathulla are relocating from New York to Miami.

Meanwhile, AQR Capital’s Cliff Asness bought a penthouse at 321 Ocean in South Beach for $26 million in May. The same month, AQR’s John Liew picked up a $13.5 million condo at the Apogee. Both of those are said to be second homes, but ones for which the owners will pay far lower property taxes than they would for condos in New York.

In addition, just before the tax law was passed, Glenwood Management’s Howard Swarzman plunked down $10.3 million for a condo at the Four Seasons Private Residences at The Surf Club in Miami Beach. And in May, developer Richard Ruben bought a $5.8 million unit in the building.

While it’s unclear if those are relocations or vacation homes, the already hot New York-to-Miami corridor seems to be stronger than ever.

Elliman’s Steinberg — who owns a home in Palm Beach — pointed out that Miami is increasingly becoming a financial hub.

Florida gained 14,700 financial services jobs during the 12 months that ended in April, according to Bloomberg. By comparison, Connecticut lost 500 similar jobs during the same time. And according to local brokers, office tours have spiked.

In addition to I Squared, which plans to open a Miami office, Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners — founded by ex-Blackstone executives — is reportedly opening an office in Austin, according to an investor memo that touted the move as a potential tax protection for executives.

In New York, Nest Seekers International’s Ryan Serhant said he sold 10 apartments this spring for clients moving out of state because of high taxes.

The “Million Dollar Listing: New York” co-star is currently marketing a $10 million Soho apartment for one-time snowbirds who decided to make Florida their full-time home.

He said his clients don’t need to sell — or necessarily want to — but the math of keeping the Manhattan apartment no longer adds up.

“It’s kind of like, the numbers don’t lie now,” said Serhant, who added that their decision to list in the middle of the spring (rather than at the beginning of fall or early spring) speaks volumes. “To be [listing] now is obviously, in part, because they’re thinking about their tax situation,” he said.

Despite the anecdotal buzz, these moves haven’t yet made a dent in property values.

“It’s a little too soon,” said real estate appraiser Jonathan Miller, noting that the softer New York market could be related to a variety of factors, like rising interest rates and general economic uncertainty in addition to tax reform.

And Elliman’s Steinberg pointed out that it’s not easy to just uproot to Florida or Texas. “When you derive your income in New York City and New York state, you can’t get around it,” he said.

Stuart Saft, who heads Holland & Knight’s New York real estate practice group, agreed. New Yorkers are still able to claim an AMT deduction, he said. And it’s extremely difficult to work in New York and avoid paying taxes here.

“You have to be out of the state 185 days a year, and the state counts it if you were in New York for 35 seconds for a day,” he said. “So you really have to give up being a New Yorker if you’re going to do that.”

Workaround wishes

Whether they’re willing to relocate or not, wealth advisors have been sniffing out workarounds for clients balking at the higher tax bills they’re facing.

One option gaining favor among estate planners involves non-grantor trusts. This essentially means putting a property into a limited liability company that’s set up in a low-tax state and then divvying up shares of the LLC into trusts that each claim the maximum $10,000 deduction.

Jonathan Blattmachr, a New York-based attorney, has advised clients to set up non-grantor trusts. And he plans to do the same with his two Long Island homes, in Garden City and Southampton, he recently told Bloomberg. After setting up an LLC, he intends to split the interest into five trusts set up in Alaska. At the end of the day, he hopes to realize a $50,000 deduction ($40,000 more than he could claim with the $10,000 SALT cap). “This is an under-the-radar thing and it’s novel,” Blattmachr told Bloomberg.

New Jersey attorney Martin Shenkman also plans to set up a non-grantor trust for his Fort Lee condo. But he said while it’s a great strategy for his wealthy clients, it’s less feasible for the superwealthy. “I had someone come in who is paying $120,000 in property tax — what am I going to do, set up 12 trusts? Is that worthwhile?” he said. “It starts to look flimsy.”

While these types of tax structures are legal, they require proactive tax planning and the financial savvy to pull off. In the short term, Shenkman said, many wealthy investors are holding out hope that their states will come in with ways to offset the new federal guidelines.

Cuomo has signed legislation that creates two workarounds to the cap on SALT deductions. One creates a state-operated charity that will accept donations in lieu of state income tax — or allow taxpayers to make donations in exchange for property tax credits. The other is an optional program for employers to pay a 5 percent payroll tax on new employees earning more than $40,000.

In May, the IRS warned that it won’t allow such workarounds, but that hasn’t stopped states like Connecticut and New Jersey from considering proposals of their own.

“People are going to feel it in their wallets, even people not making a ton of money,” said Aaron Lerner, a senior manager at accounting firm EisnerAmper. “The states may be in a position where they have to give deductions in order to stay competitive in the market for talent and business.”

According to Lerner, investors may be eligible for a 199A deduction of 20 percent of their income if their taxable income related to real estate investments is under $400,000.

Others are turning to 421a tax breaks. Warburg Realty’s Alex Lavrenov said he’s steered clients toward condos with tax abatements. He recently helped clients sell an apartment in Greenpoint for $999,000 and purchase a larger place — with a 421a abatement — in Windsor Terrace for $1.2 million. “They kept relative monthly costs down where they could maintain the same lifestyle,” he said.

But Back Roads’ Gaines said his monthly costs will drop while his lifestyle improves. He’ll be able to send three children to private school in Texas for the cost of one in New Jersey. And he has extended family nearby.

“I’m pro-Jersey, but it has almost 9 percent state income tax,” he said. “The exodus is apparent to everyone.”