Raphael Toledano has difficulty staying still. On a recent afternoon, the stubble-faced real estate wunderkind sat in his office, dressed in a black suit and leather slip-on shoes that he said he designed himself. He alternated between puffing on cigarettes — both tobacco and electronic — eating fresh mango slices and popping pills for a headache.

Before commencing the interview, Toledano, a Sephardic Jew who prays three times a day, wondered aloud about the ethics of journalists. “Do you believe in God? Yes or no?” he asked this reporter. Once at ease, the 26-year-old investor proceeded to launch into a mile-a-minute monologue about his achievements that often included frat-tastic boasts about his wealth.

“I’m worth a fuckload of money, bro,” he said.

The statement was all the more remarkable considering that just five years ago the New Jersey native was waiting tables.

In an industry known for colorful personalities, Toledano — who goes by the nickname “Rafi” — has emerged as an unlikely up-and-coming player in the city’s competitive multifamily market. Over the past nine months, he has become one of the East Village’s biggest landlords, after his investment firm, Brookhill Properties, agreed to buy 28 buildings in two separate portfolios from the Tabak family for a combined $140 million. He currently owns more than 400 units — counting only the buildings he’s already closed on.

Altogether, Toledano values his entire portfolio, the bulk of which are aging East Village walk-ups, at $500 million.

Toledano’s plan is to rehab the units, paving the way for destabilization and rent hikes. It’s a playbook move for multifamily investors. But listen to him talk, and he might as well be building on Billionaires’ Row.

“I consider myself the ultimate of developers because I’m taking a run-down, neglected building and developing it,” he said. “Gary Barnett has the easiest job — he gets vacant land, he gets an architect, a good contractor, and he builds up. For me, it’s not like that.”

Yet if Toledano’s swagger and rapid ascent have made him a talked-about figure in New York real estate circles, so has his controversial track record.

Since February 2014, he has been slapped with at least eight lawsuits — from tenants, a would-be lender, an office landlord and, most notoriously, his uncle, Aaron Jungreis, one of the city’s top multifamily brokers.

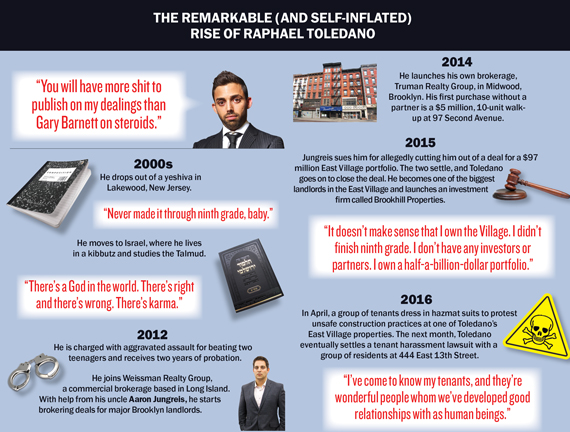

In August 2015, Jungreis sued Toledano for allegedly cutting him out of a $97 million purchase of one of the two Tabak portfolios. According to court papers, Jungreis accused his nephew of betraying his trust after he had mentored him and shared his professional network with him. The two eventually settled their dispute out of court, but not before grabbing headlines and spurring industry gossip.

Other scandals have followed. Brookhill and independent property manager Goldmark Property Management are under state investigation for alleged tenant harassment at his East Village building at 444 East 13th Street. And this past December, The Real Deal discovered that Toledano may have used a fake law firm to solicit new business.

Other scandals have followed. Brookhill and independent property manager Goldmark Property Management are under state investigation for alleged tenant harassment at his East Village building at 444 East 13th Street. And this past December, The Real Deal discovered that Toledano may have used a fake law firm to solicit new business.

Experienced real estate players have also raised red flags about Toledano’s heavy reliance on debt. In 2015, Toledano landed $158 million in financing for two deals from Madison Realty Capital. In the aforementioned $97 million deal with the Tabaks, for example, he took out two mortgages from Madison, totaling $124 million. New York City multifamily deals are leveraged at an average 50 to 65 percent — Toledano’s deal, by comparison, comes out to 128 percent.

“He’s working on the edge and pushing the envelope,” said Bernard Miller of Parkway Realty Associates, a veteran investor who has worked with Toledano on several deals in Brooklyn. He noted that the latter has always been “above board” with him.

Still, he added: “He’s overleveraged and pushing up rents to pay off a high mortgage.”

For his part, Toledano denies being overleveraged.

He said that for the $97 million Tabak portfolio alone, Brookhill invested $15 million of its own money — earned from flipping contracts, as well as his former brokerage business — toward renovations. He explained that he prefers not to have equity partners on deals.

As for the lawsuits, he suggested that they were just par for the course.

“When you go from zero to 60 in three seconds, sometimes you exceed the speed limit,” he said.

Unlikely beginnings

Toledano’s rise is all the more stunning considering his start. One of six children, he grew up about 80 miles south of Manhattan, in Lakewood, New Jersey, where nearly half the population is Orthodox Jewish. His mother worked as an independent real estate broker, while his father ran a book publishing company.

Despite his religious upbringing, Toledano had a rebellious streak. Early into high school, he dropped out of a yeshiva, a fact he now takes pride in. “Never made it through ninth grade, baby,” he said. A source who has known him for years described him as a “street kid in Lakewood.” After leaving school, Toledano lived in Israel, on and off, studying the Talmud in a kibbutz, he said.

In 2012, he returned to the U.S. for good. At 22, and without a formal education, he decided to go into real estate. But just two weeks after he obtained his New York salesperson’s license in March 2012, he was charged in New Jersey with aggravated assault and causing bodily injury. According to police reports, he beat two teenagers with a crowbar over what appeared to be an altercation involving his sister.

He was convicted and received two years of probation.

He wound up moving to Far Rockaway, Queens, and joined Weissman Realty Group, a commercial brokerage in Lawrence, a town in Long Island. Once there, Toledano rose fast. He worked on commercial deals in Brooklyn that he landed by cold-calling and cultivating relationships, said Mark Weissman, a broker and attorney who runs the firm.

Toledano said the job at Weissman offered him a crash course in the challenges of brokering big deals. “One time, I brokered a $10 million deal where I made a $400,000 commission,” he said. “The day the deal’s supposed to sign, it doesn’t because of a rent overcharge claim. Your $400,000 commission is on the line. You very quickly learn what rent overcharge means. And you very quickly learn how to fix it.”

At Weissman, he was brokering deals in the $2 million-to-$12 million range for prolific Brooklyn-focused landlords such as BCB Property Management, Miller’s Parkway Realty and Shamah Properties.

97 Second Avenue

While he was by all accounts hardworking, he had a key industry connection in Jungreis, who is married to his aunt and roughly two decades his senior. His uncle helped Toledano get into the multifamily brokerage business, partnering with him on deals for small walk-ups in Upper Manhattan and Brooklyn. Toledano would represent one side and Jungreis the other.

Brokering proved to be a natural gateway to investing. “Through selling some of these deals, I started realizing that the money is really in owning it,” Toledano said.

In 2014, he launched his own Brooklyn brokerage, Truman Realty Group, to both broker outside deals and handle his own acquisitions, including his first purchase without a partner — a $5 million, 10-unit walk-up at 97 Second Avenue in the East Village, in April 2014. Initially relying on financing from small-time private Brooklyn investors, he also snapped up buildings, including one with Jungreis, in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Sheepshead Bay and other Brooklyn neighborhoods. He said he has since sold all of his Brooklyn properties.

He said Truman “facilitated, syndicated and structured” about 50 investment sales deals in 2015, worth a total of $700 million. That includes $225 million of his own purchases.

Working on the edge

But by far, his breakout deal was the Tabak portfolio. The family, led by patriarch Morton Tabak, has had a stronghold in the East Village. The Tabaks knew Toledano. Back in 2014, Toledano cold-called Tabak’s daughter Janet Garfinkel and wound up brokering the family’s sale of a small Kips Bay portfolio to Madison Realty Capital.

The following year, when the Tabaks were looking to sell a large chunk of their holdings, Toledano came calling as a suitor.

Initially, he sought a partner in the deal. According to Jungreis’ lawsuit, he and Toledano had made an oral agreement to buy the properties together. But Toledano signed a contract to buy the buildings solo. Jungreis claimed Toledano was “motivated solely by greed.”

The two have spoken little since settling out of court.

Asked to comment, Jungreis said, “I’ve let bygones be bygones. I wish him the best of luck in his future purchases.”

Toledano declined to comment on the matter.

Within the real estate community, the dispute between Toledano and Jungreis, a well-respected broker in the industry, raised eyebrows and furthered the perception of Toledano as underhanded and willing to succeed at all costs.

“Sometimes he tiptoes on the line, but that’s how people become very successful,” said David Amirian, a developer who is a friend of Toledano’s.

Another blow came last December, when TRD reported that someone using the name Raphael Toledano had in 2014 sent out a letter to a New York City landlord claiming to be a lawyer with a Park Avenue law firm called Truman & Wildes LLP. The letter’s author claimed to be representing the co-founder of Madison Realty Capital, Josh Zegen, in a 1031 exchange, which allows sellers to defer capital gains taxes if they reinvest in another property. The letter said Zegen was interested in one of the landlord’s buildings and assured him that his client would “pay above market value.”

But Zegen told TRD that his firm has “never hired [Toledano] in any capacity to represent us in any which way.”

The landlord, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told TRD that Toledano had even called him to talk about the property. He said he suspected Toledano pretended to be a lawyer to gain better access.

The law firm proved to be a fake. TRD discovered that it’s not registered in the tristate area. It did, however, have a Brooklyn address that matched that of Toledano’s now-shuttered Truman Realty Group.

The website for Truman & Wildes was taken down after TRD began making inquiries. Toledano has denied the allegations.

Tenant accusations

Although he has been a landlord for more than a year, Toledano has shot to notoriety. Several news outlets, including TRD, have reported on alleged tenant harassment and hazardous living conditions at his buildings.

In April, a group called the Toledano Tenants Coalition, which has about 150 tenants across more than 20 of his buildings, dressed in hazmat suits outside of Brookhill’s office as part of a protest against alleged unsafe construction practices during renovations. When asked about the coalition, Toledano said in a statement, “Even though this is a very small percentage of the tenants in buildings that I own, I take every concern seriously and work immediately and tirelessly to remedy any situation brought to my attention that merits remediation or repair.”

Meanwhile, just last month, Gothamist reported that the city was planning to test 20 buildings owned by Toledano for lead. Prior tests at three of his buildings found that lead-dust levels far exceeded federal standards — in one case by 16 times.

“This guy is second in line to Croman,” Holly Slayton, a rent-stabilized tenant at 514 East 12th Street, told TRD, referring to the notorious landlord Steven Croman, who was recently charged with 20 felonies, partly stemming from cases of tenant harassment.

She said when she expressed concerns to Toledano about her 8-year-old daughter’s exposure to dust resulting from work in neighboring units, he offered to move her to another rent-stabilized building in Murray Hill that he owns, but never followed through.

Slayton, who is also an agent at Nest Seekers International, pays $1,525 a month for a two-bedroom unit, one of several in the building that she said Toledano wants to lease for north of $3,600 per month.

In response to Slayton’s complaint, Toledano said, “We pride ourselves in the integrity we maintain at Brookhill Properties in all of our business relationships. Our top priority is to provide tenants with a residence that meets the highest standards of health, safety and comfort.”

Raphael Toledano (Photo by Michael McWeeney)

Perhaps the most damning case involved a group of tenants at another Toledano building, 444 East 13th Street. Last year, the tenants sued Toledano and the management company at the time, Goldmark, for harassment. As evidence, they offered up secretly recorded conversations with an agent representing Toledano that they argued amounted to scare tactics — ranging from warnings of steep rent hikes to pending construction next door expected to create unlivable conditions — to get them to move. The lawsuit was reported by the New York Times, which also published the recordings on its website.

Toledano pinned the blame on Goldmark, which he fired. Paulius Skema, who owned Goldmark, declined to comment except to say he was no longer affiliated with the company. He now runs an investment firm called Trifecta Equities with Ralph Hertz, Toledano’s cousin.

As part of a settlement with the tenants, Toledano agreed to pay north of $1 million, multiple sources said.

But he could face further charges or fines. The state attorney general’s office and a tenant-protection unit have been jointly investigating harassment claims at the building.

Toledano spoke of having a positive relationship overall with his renters and said he has made donations to a local soup kitchen and community garden.

“The Village as a whole has got beautiful tenants,” he said. “I’ve come to know my tenants, and they’re wonderful people whom we’ve developed good relationships with as human beings.”

Risky loans?

Apart from his reputation as a landlord, how much Toledano owes — and to whom — has raised questions about whether he’s at risk of forfeiting his properties.

In both financings provided by Madison Realty Capital, the size of the mortgages closely mirrors — or is substantially higher than — the purchase price. However, one important point to take into account is that the loans are intended to cover renovation costs as well as the acquisitions. Regardless, sources are skeptical about the ability of Toledano to pay them off in time. The first and second mortgages for the $97 million Tabak purchase, for example, are due in one to three years.

A source at a real estate capital advisory firm who is not affiliated with Madison or Toledano said Madison’s services are more tailored to the investor than that of a traditional bank because the loans consist of multiple rounds of funding. “Madison’s position is, ‘I get that this is where you are at [with funding]. Here are increments of leverage as you achieve each of these hurdles in the acquisition and renovation process,’ ” the source said.

The actual total costs stemming from the $97 million Tabak portfolio will likely far exceed the $124 million loan provided by Madison, the source said, adding that it would not be uncommon.

But Toledano probably doesn’t have much choice. While he did secure a $5 million refinancing loan in May 2015 from Signature Bank for his $5 million purchase of 97 Second Avenue, that was a relatively small sum and prior to the wave of bad press. Today, a major national bank would give particular scrutiny to Toledano’s background — any negative media coverage, lawsuits or building violations — and the rent-stabilized buildings’ in-place cash flow. A source who works at a large bank said it’s apparent that Toledano went to Madison to secure high leverage at very high rates. He said Toledano likely hopes that by levering up the property, he can turn the units over fast enough to generate a profit.

It might backfire. Madison has been accused of aggressive, if not illegal, practices. In January, the company was accused by SMK Property Management in a $150 million lawsuit of a predatory lending scheme over seven defaulted mortgages in Greenpoint. Madison claimed SMK owed the firm $15 million.

Madison also provided a $34 million loan in 2015 for Toledano’s $41.5 million purchase of a 39-unit Chelsea rental building. He initially sought to build a two-floor, 20-unit addition, which would have been his first significant development. But he shelved the plans, explaining that he intends to focus on buying and fixing up properties for now.

A top investment sales broker, who asked to remain anonymous, said that given Toledano’s legal problems and other circumstances, he didn’t expect Zegen to partner with Toledano on deals. “Josh Zegen didn’t go into this as a shark, but he probably wouldn’t mind taking over a portfolio like that at those numbers,” he added.

Zegen declined to comment.

Regarding Madison, Toledano said, “I have a lot of respect for [Zegen] and his fund.”

Going long

Yet again, it’s quite possible that if anyone can weather a storm, it’s the fast-talking and intensely determined Toledano.

“He’s resilient,” said Yekusiel “Kus” Sebrow, a Weissman Realty agent who worked with Toledano from 2012 to 2014. “He gets past all these things.”

Following the $97 million Tabak deal in the fall of 2015, Toledano closed Truman’s Midwood office and launched Brookhill, which opened at 298 Fifth Avenue in NoMad. In April, the firm relocated to a short-term space in Midtown East and later this year will move its 50 employees into a new main office — a full-floor, 15,000-square-foot space at 826 Broadway, in Union Square.

Toledano’s sights are now set on the West Village. He said he is close to buying a large portfolio in the neighborhood but declined to provide details.

While he recently sold a few buildings in Murray Hill and Gramercy Park for an undisclosed price, the core East Village assets, he said, he will keep “for eternity.”

“I don’t like the concept of selling real estate,” said Toledano, who lives on the Upper West Side and is expecting his first child with his wife, Devorah. “These are things I buy to own and to pass on to my kids — and to pass on to their kids.”

Aside from real estate, he is working to launch a new line of shoes he designed in partnership with a Portugal-based shoemaker. After switching to custom suits, he said he was inspired to dabble in fashion. It’s not the first time he’s looked for entrepreneurial opportunities. In 2011, when he was working as a waiter, he applied for a license to open a catering company called Raphael’s Catering. Ultimately, however, the idea never got off the ground.

Toledano is well aware of his uncanny, accelerated rise.

“It doesn’t make sense that I own the Village,” he said emphatically. “I didn’t finish ninth grade. I don’t have any investors or partners. I own a half-a-billion-dollar portfolio.”

In a rare moment of stillness, Toledano paused. He then added: “There’s a reason and a destiny.”