During the boom, purchasing a new condo was like buying Manolo Blahniks or an Armani suit: Shopping in an elaborate showroom, buyers wouldn’t dream of offering less than the sticker price.

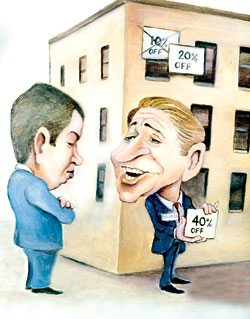

These days, the showrooms are still around, but the process is more like haggling at a flea market.

Asking prices for new condos — the figures quoted in online listings and in advertisements — now have little to do with the final sale price. While developers are reluctant to lower their official prices, units are selling for anywhere from 5 to 30 percent less than the sticker price, brokers say. That’s a huge change from just a few years ago, when the prices of new condos were considered nonnegotiable.

Developers “are not willing to bring down their asking prices, and some have list prices that have been around since the beginning of the recession,” said Laurielle Noel, a sales and listing specialist for Platinum Properties. “If you come in and start negotiating, they can come down, depending on the situation, 15 to 30 percent. The asking price is not really reflecting what they’re closing at.”

In the days before Lehman Brothers collapsed, buyers accepted the high costs of new condos without hesitation. If anything, they assumed prices would soon rise in the booming real estate market, said Ana Maria Sencovici, a sales associate at the Real Estate Group NY. “You really didn’t have much leeway,” she said.

Nowadays, nearly every asking price is negotiable.

“The ask is less important now than it has been in some time,” she said.

Noel, who often represents clients looking to buy new condos in the Financial District, said, “On any given day, I can walk in with a client to several buildings and say, ‘This client is looking for a one-bedroom in the $700,000 range.’ The listing agent will look at the list of apartments priced at around $800,000 or $900,000, and say, ‘You can get this one for that price.'”

Noel recently had an international client who was looking at Financial District apartments in the $1 million range. The buyer ultimately paid just under $1 million for a unit listed at $1.2 million.

Rather than telling the buyers up front what kind of discount is available, some listing brokers say they are “encouraging offers” — a thinly veiled invitation to offer less than the asking price, explained Core’s Kirk Rundhaug, who often represents buyers in new construction buildings.

“They’re telling you, ‘Go ahead and make an offer, and we’ll tell you if it’s too low,'” said Rundhaug. He is also the exclusive sales agent at boutique condo development 32 Clinton, where “there’s a little bit of room for negotiability,” he said.

Many developers have officially adjusted their prices at least once since the Lehman Brothers collapse.

Why don’t they do it again?

Easier said than done, explained Andrew Gerringer, managing director of Prudential Douglas Elliman’s development marketing group.

Unlike ordinary home-owners, developers can’t raise and lower their prices at will — they first have to get permission from their lenders, and amend the offering plan that has been filed with the Attorney General’s office. Without an amendment, a developer can’t advertise prices different from those in the offering plan — not even in e-mail blasts or Web listings.

As a result, it’s often easier to simply negotiate with buyers one-on-one, especially since developers hope to raise their prices again as time goes on.

That was the strategy at Chelsea Enclave, where unit #2B was last listed for $2.49 million in April 2009 after an earlier price cut, according to James Lansill, a senior managing director at Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group, which is handling sales at the project.

The apartment went into contract this fall at $2.025 million, he said, one of several deals where the sales team “did some significant negotiations to get momentum going.”

The developer negotiated big discounts on a few units rather than doing another across-the-board cut, Lansill said, because “once the building reaches a higher percentage sold, we will grow into these prices again.”

Some developers fear that making a deep, public price cut will give the appearance of financial distress.

“They’d rather deal behind closed doors than look like they’re in liquidation,” Noel said.

Moreover, buyers these days insist on negotiating, said Henry Justin, the developer of 211 East 51st Street in Sutton Place. Before the Lehman Brothers collapse, Justin said he was selling units in the building at an average of $1,250 to $1,300 per square foot. He’s now cut his listing prices to around $1,200 per square foot, which means he stands to lose at least $5 million on the project, he said.

Still, he’s finding that he needs to negotiate even further in order to get deals done. “People come into the building and expect you to take 10 percent off,” he said.

Knowing that buyers want to bargain, many developers now price their units with negotiability built in.

“Some keep prices where they are, so it looks like a bigger discount,” Gerringer said. “If you’ve lowered prices already, your negotiability would be much less.”

Still, asking prices have to be competitive, or buyers will simply avoid the building altogether.

“You always have to be within the market,” Gerringer said. “If someone else is at $1,200 a foot and you’re at $1,500 a foot, where is that going to get you?”

How much a developer can negotiate depends on how many units they’ve sold, the flexibility of their lenders, and how long the project has been on the market, according to Kelly Kennedy Mack, president of Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group.

As the economy improves, many developers are finding that they don’t have to be quite as flexible on price. “As the market is getting stronger, the negotiability factor is getting smaller,” Mack said.

Lansill said developers are now more likely to give discounts in the range of 4 to 12 percent off the listing price, compared to 20 to 30 percent last summer.

During the worst of the real estate slump, Justin said he sold some units for as little as $1,075 per square foot. Now that his building is 60 percent sold, however, he tries to go no lower than $1,150.

Still, Noel said she tells clients not to automatically exclude a building from their search even if it appears to be priced as much as 35 percent above their price range.

“I tell clients, ‘Look, I’ve brought many clients to these buildings, I know what the real prices are,'” she said. “Most of the time they’re happy to check it out — people always want an upgrade.”