In the fall of 1991, a brash New York developer testified at a Congressional budget hearing, telling committee members that nobody he knew could get a loan and complaining that the real estate industry’s muscle in Washington was weak.

“They have absolutely the most pathetic lobby in the history of the United States Congress,” a then-bankrupt Donald Trump said during the hearing, which was focused on how to help the U.S. economy recover amid a deep recession.

“It’s a shame,” he said, “that this very powerful and important industry doesn’t have a better lobby.”

Today, of course, Trump is the primary resident of the White House, and rather than relying on lobbyists to push his agenda, he is the target of their influence peddling.

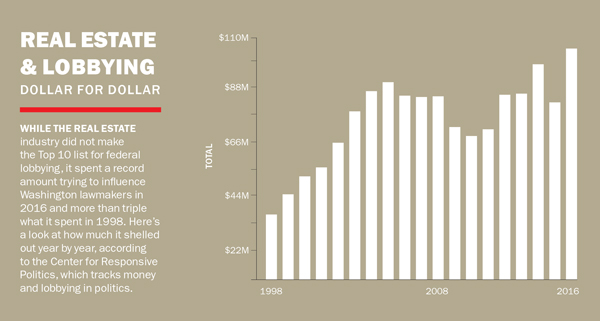

The real estate lobby has grown massively since the day Trump testified in front of that House of Representatives committee.

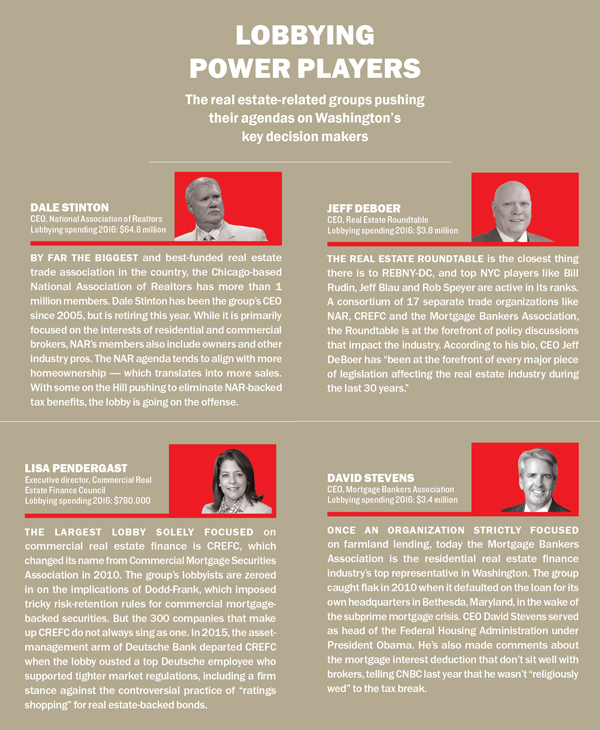

In 2016, the industry pumped nearly $104 million into federal lobbying — more than the securities and investment industry, which includes the bulk of Wall Street interests apart from the major banks. The industry’s biggest spender — the National Association of Realtors — was second only to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in total spending by any company or group from any industry between 1998 and 2016, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan research group that tracks money and lobbying in politics. NAR, which has 1.1 million members, spent a massive $416 million on its reported lobbying during that time. By comparison, the megafirm General Electric shelled out $345 million, the defense contractor Northrop Grumman dropped $243.4 million, and Boeing and Exxon Mobil ponied up $242.9 million and $232.2 million, respectively.

Despite NAR’s might, the real estate industry still doesn’t have the same kind of presence in Washington as other major industries — like big oil, telecom and health care. But sources say that’s largely because real estate is less consolidated, with stakeholders ranging from residential developers to commercial landlords to mortgage players to the big banks, among others.

Real estate did not make the Center for Responsive Politics’s Top 10 list for lobbying dollars spent between 1998 through 2016. But its spending is on the rise. The $104 million it spent in 2016 was a record, up 26 percent from a decade earlier.

“While overall lobbying has been declining, real estate for whatever reason has kind of been increasing since they recovered from the collapse,” said Daniel Auble, a senior researcher at the nonprofit.

Real estate lobbyists said that in addition to targeting Congress, they’ve also recently been focusing more on federal agencies.

Bill Killmer, the chief lobbyist for the Mortgage Bankers Association — which has more than 2,000 corporate members — said the push to lobby agencies on mortgage finance issues started before the passage of Dodd-Frank, which was signed into law under President Barack Obama in 2010 and designed to increase regulation on the unwieldy banking industry after the financial crisis.

“I used to say our regulatory folks were drinking through a fire hose on a daily basis because there was so much interaction we had to have with the alphabet soup of regulators,” Killmer said, referring to the dialogue about the changing rules. “I think we tried to maintain a pretty even balance [between agencies and Congress].”

Now, with one of their own in the Oval Office, many in the industry are hoping for an onslaught of pro-real estate changes and more face time with the president or his surrogates. Sources say Bill Rudin and several other New York developers recently met with Ivanka Trump and White House economic adviser Gary Cohn in Washington.

So far, however, much of the access has come not at the White House but at the president’s private club Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, where he’s hosted friends and real estate titans Richard LeFrak, Howard Lorber, Bruce Toll and others.

In addition to having Trump in the White House, the fact that both the Senate and House are controlled by Republicans means that the legislative environment for most major real estate issues hasn’t looked better in years.

“The House has passed a lot of legislation that didn’t go anywhere in the Senate that may go somewhere now,” said Ken Trepeta, president of the Real Estate Services Providers Council, a national industry lobby.

“Some things that weren’t possible in the last eight years are now possible,” added Trepeta, who helped write the Mortgage Choice Act, which falls under the Financial Choice Act.

“Some things that weren’t possible in the last eight years are now possible,” added Trepeta, who helped write the Mortgage Choice Act, which falls under the Financial Choice Act.

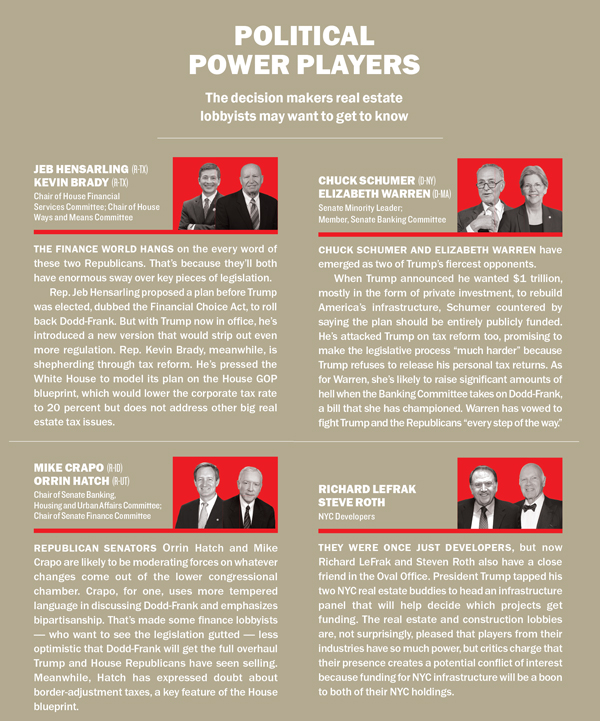

Last month, Texas Republican Jeb Hensarling — chairman of the House Financial Services Committee — reintroduced the Financial Choice Act, a bill designed to roll back Dodd-Frank that was shelved in December. The new version even more severely strips it of its regulatory teeth.

But reforms to Dodd-Frank — along with tax reform, the reauthorization of the EB-5 program, infrastructure spending and more — took a back seat to President Trump’s failed push to repeal Obamacare and his controversial (but ultimately successful) nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. With the administration now moving on from those matters, real estate-related reforms are next.

Below is a rundown of some of the key issues that the real estate lobby is watching and mobilizing on.

Tax reform

When President Ronald Reagan and his Senate allies pushed to raise taxes in the early 1980s, the real estate lobby was relentless.

“They have been camping on our doorstep,” said then-Sen. Bob Dole, the legendary Kansas Republican. “They have been in the gallery. They have been in the lobbies. They have been in the elevators.”

The lobbyists’ persistence paid off: The real estate industry managed to hold onto a slew of special tax breaks. But the victory was short-lived.

A few years later, in 1986, tax reform rose to the top of Congress’s priority list, and real estate tax shelters — which had exploded in popularity between the late 1970s and early 1980s, in part because of changes made to capital gains taxes — became a key target.

Although no concrete numbers exist, Wall Street Journal reporters Alan Murray and Jeffrey Birnbaum wrote in their 1988 book “Showdown at Gucci Gulch” that the money stashed away in tax shelters in the U.S. jumped to $20 billion from $2 billion during that time. Tax shelters became a go-to mechanism for filling developers’ capital stacks because they allowed investors to offset their tax burdens while investing in real estate.

But when Congress eliminated many of those tax shelters as well as deductions for passive-investment losses, real estate investment dropped off, industry sources say.

Today, with tax reform at the top of Trump’s agenda, industry players all agree on one thing: Never let 1986 happen again. “I was here in 1986,” said Cindy Chetti, lobbyist for the National Multifamily Housing Council, a prominent landlord group, “and many of us remember what the outcome of the tax reform effort was and the problems it created for the commercial real estate industry.”

That’s why the prospect of any major tax overhaul — even one backed by a developer-in-chief — has the entire real estate lobby on alert.

The Trump administration and House Republicans have called for sweeping changes to taxation, leaving concerns that tax benefits for real estate investments — including 1031 exchanges, carried-interest deductions, the mortgage-interest deduction and the low-income housing tax credit — might get axed (or altered) in the hunt for extra revenue.

The Real Estate Roundtable — a consortium of real estate trade associations with close ties to the Real Estate Board of New York — and NAR are already emerging as two of the industry’s leading lobbyists on tax reform.

In January, the Roundtable released its Trump-era policy agenda, touting 1031 exchanges, which allow investors to defer tax payments when they reinvest the proceeds from the sale of one property into another. A preliminary “blueprint” proposed by the House Republicans last year was silent on 1031 — as was the tax plan announced late last month by the Trump administration. Real estate sources contend that the elimination of the exchanges would have devastating effects on New York City’s investment sales market because they incentivize sellers to buy new properties, thereby generating more business.

The halls of Congress will be crowded with lobbyists from the broader business world vying to make their tax priorities known. And at the top of many of their agendas is something else: the corporate income-tax rate.

The Trump administration has called for the current rate of 35 percent to be dropped to 15 percent. The new rate would apply not just to large corporations, but also to smaller businesses and pass-through entities such as LLCs, which are used widely in commercial real estate. In their blueprint, House Republicans proposed lowering the rate to 20 percent for corporations and 25 percent for pass-throughs. But without increasing the federal deficit, it will be hard, if not impossible, to make across-the-board tax cuts unless revenue is raised elsewhere.

John Bryant of the Building Owners and Managers Association International — an organization whose members oversee 10 billion square feet of commercial property in the U.S. — said the group is staying focused on the final outcome.

“The response we’re getting when we’re talking to the tax-writing committees is ‘Don’t just look at the individual parts … if you look at the end game, it will actually be a wash or you may actually come out better,” he said.

Although Bryant and others are still advocating for the tax breaks that currently benefit the industry, as long as the overarching math works out for them, they’re keeping an open mind.

“We’re not drawing a hard line in the sand,” Bryant said.

Dodd-Frank

Just the mention of Dodd-Frank gets stakeholders on both sides of the political aisle riled up — with opponents arguing that it saddles the banking industry with too many restrictions and cripples the economy, and proponents saying it’s badly needed to protect the public from the loosely regulated banks that prompted the 2008 financial crisis.

Trump has blasted the legislation, vowing on the campaign trail to “dismantle” it.

In February, the president signed an executive order directing his Treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, a former hedge funder and Goldman Sachs executive, to evaluate the Dodd-Frank-created Financial Stability Oversight Council and report back within 120 days on whether it’s acting in line with his goals for a less-regulated economy.

In February, the president signed an executive order directing his Treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, a former hedge funder and Goldman Sachs executive, to evaluate the Dodd-Frank-created Financial Stability Oversight Council and report back within 120 days on whether it’s acting in line with his goals for a less-regulated economy.

“We expect to be cutting a lot out of Dodd-Frank, because frankly I have so many people, friends of mine, that have nice businesses and they can’t borrow money,” the president said in a February meeting with business leaders who included Stephen Schwarzman, CEO of the fund manager Blackstone Group.

While Dodd-Frank is targeted squarely at the banking industry, it is inextricably tied to real estate lending — from residential mortgages to construction loans to investment dollars. And for the industry, Dodd-Frank will be one of the biggest legislative battlegrounds.

Lobbyists, especially in the commercial sector, are carefully strategizing as they assess the rules — some of which have only very recently gone into effect.

Meanwhile, Hensarling’s new bill — which would ease regulations on mortgage lending as well as reduce the “risk retention” burden on banks that requires them to keep extra capital on their books — addresses real estate players’ concerns. But Democrats argue that the bill will put millions of consumers at risk.

Whether Hensarling’s bill moves forward or not, risk retention will undoubtely be under the microscope for the real estate industry. At the moment, it requires banks packaging commercial mortgages into sellable securities to keep 5 percent of those loans on their own books.

Two of the most prominent real estate lobbying groups taking on Dodd-Frank are the Commercial Real Estate Finance Council and the Mortgage Bankers Association, which are focused on the commercial and residential components of the legislation, respectively.

David Motley, the chairman-elect and president of the mortgage group, recently said the regulations have “reduced the availability and affordability of mortgage credit for many American families.”

Marty Schuh — the senior director and head of government relations at CREFC, who was a staffer for Republican Sen. Bob Corker when Dodd-Frank was being hashed out — said the legislation incited confusion because the procedures for implementing it were unclear.

“We had all kinds of little fights, about what the value of par,” Schuh said, referring to disputes while the legislation was being drafted about how various portions of it would be interpreted.

Major bank heads including JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon are not seeking to repeal the entire bill, but to instead to “open it up” and reassess.

“I’m not someone for wholesale ‘throw it all out,” Dimon told Bloomberg in January. But he added that “no one in their rational mind could say everything that was done and how it was done was done right.”

He cited liquidity-ratio requirements for banks as well as operational risk capital — both of which dictate how much money banks need to keep on hand — as areas for potential change.

But risk retention in general is complicated for many lobbying groups. CREFC represents both CMBS buyers and sellers and has a less hawkish stance than might be expected. While it might have technical issues with the way the rule functions, it’s not opposed to risk retention generally.

“CREFC always supported the idea of skin in the game because we are ultimately driven by the buy side — they’re the keys to this being a successful market,” Schuh said.

Some sources argue that the importance of these regulations to the success of the current market is overstated.

“While the regulatory environment is playing a role in some kinds of lending, concerns about pricing and where we are in the market cycle are also significant factors,” said Sam Chandan, an associate dean of NYU’s Schack School of Real Estate.

Still, much of the home lending industry argues that aspects of Dodd-Frank have limited the ability to extend debt.

The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau — a body created by Dodd-Frank — issued a slew of new regulatory guidance, including Dodd-Frank’s qualified mortgage rule, which tightens banks’ discretion in deciding who qualifies as a “good faith” borrower.

Killmer, of the Mortgage Bankers Association, said that above all he’s “arguing for regulatory clarity.”

“We’re not necessarily trying to blow up all those systems, we’re trying to see if there are ways to improve them.”

Affordable housing

To get a sense of how affordable-housing construction might be shaken up by Congress, lobbyists and stakeholders need to trace the history back to 1986 — again.

That’s when, after cracking down on tax shelters — a move that led to a drop in multifamily investment — lawmakers designed a dollar-for-dollar tax break known as the low-income housing tax credit, or LIHTC in industry-speak. Developers win the credits from the state, get them from the IRS and then sell them on an open market. In 2015, the LIHTC market raised about $13 billion in equity, according to the accounting firm Novogradac & Company, which tracks the market.

These tax credits have become a crucial incentive for any developer in the affordable-housing space. Without them, sources say, many affordable residential projects don’t pencil out financially.

Bob Moss, director of government affairs for the New York-based accounting firm CohnReznick, said that although he’s concerned, the program’s wide popularity in Congress makes him hopeful that LIHTC will not be on the chopping block.

“We’ve been invited in by the Ways and Means tax staff to start talking about financial models that would maintain the low-income housing tax credit production … should corporate rates be lower,” said Moss, whose firm does extensive work in affordable housing.

“We have very much been at the table,” he added. “We have not felt like we’re on the menu.”

But with the expected drop in corporate taxes, prices for these credits are already falling. That’s because a drop in corporate tax rates means those who are buying these credits have less tax liability to offset. And that means less demand.

Still, many affordable-housing advocates are not overly worried about LIHTC, and there’s even talk of expanding the number of available credits.

In March, Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington state, introduced legislation — which already has bipartisan support — to expand the number of available credits by 50 percent.

Other affordable-housing programs may not be so lucky.

The White House budget office released its proposal for the Department of Housing and Urban Development in March, which included a massive $6.2 billion slash in spending. The move was backed by Trump’s HUD Secretary Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon who ran against Trump in the GOP presidential primary and has, until now, never held a government position.

The White House’s budget blueprint also proposed abolishing Community Development Block Grants, which are widely used in New York to help fund code enforcement, building inspections and even emergency repairs to some privately owned buildings if a landlord refuses to rectify a safety issue.

National affordable-housing groups like the National Low Income Housing Coalition and the National Housing Conference are now busy making their case for why Trump’s unprecedented cuts to housing would be detrimental to the American poor. “These proposed cuts are unacceptable, and Congress must soundly reject them,” Diane Yentel, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, wrote in a letter after the White House announced its intentions.

“There’s already close to a $30 billion capital-needs backlog in public housing across the country,” Yentel told The Real Deal in an earlier interview.

National Housing Conference President Chris Estes, meanwhile, told his members to prepare “for ongoing, coordinated advocacy for housing and community development. This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

GSE reform

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — public companies known as government-sponsored enterprises — guarantee trillions of dollars in American mortgages. The two GSEs, which were created to expand the nation’s secondary mortgage market, were hemorrhaging money amid the subprime mortgage crisis and were bailed out to the tune of a stunning $187 billion by the federal government.

In September 2008, with President George W. Bush in the White House, they were placed into government conservatorship. At the time, the Washington Post described the move as “one of the most sweeping government interventions in private financial markets in decades.”

But most agree that having the government in control of Fannie and Freddie’s books is not sustainable.

Treasury Secretary Mnuchin has said Americans should expect GSE reform sometime during the Trump administration. Although Trump does not have a public stance on GSEs, in late November Mnuchin called for a swift end to “government control” of Fannie and Freddie. He later clarified that he’s not looking to abolish them.

In February, Cohn, Trump’s economic advisor, told reporters that Mnuchin has been “spending a lot of time” on GSE reform and described it as an “early” priority.

But Jamie Gregory, the chief deputy lobbyist for NAR, said he expects the issue to take a back seat to tax reform for now. “We’ll see legislation introduced and we’ll see hearings this year, but I think ultimately it’s far more likely a bill passes next year,” Gregory said.

NAR, along with the rest of the national real estate lobby, wants to ensure that whatever GSE plan moves forward, U.S. mortgage lending remains robust.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency — which oversees Fannie and Freddie — has warned that the two GSEs are at risk of needing another bailout if something doesn’t change soon.

Fannie’s capital buffer is on track to hit a big fat zero in early 2018, at which point it will need to hit up the U.S. Treasury. Freddie, meanwhile, started 2016 with a $354 million loss.

Yentel, of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, said one reason the Treasury would be on the hook is because Fannie and Freddie’s current structure prevents them from holding too much capital.

“The agreements they have … ensure that the capital buffers of Fannie and Freddie are ever-declining,” Yentel said. “That increases the likelihood that Fannie and Freddie will need a draw from the Treasury.”

The coalition and other affordable-housing groups will be lobbying to keep the so-called National Affordable Housing Trust Fund intact. That fund is financed by Fannie and Freddie, but if the GSEs need to tap the Treasury, they can’t pay into the trust.

“The longer we go without some resolution … the more at risk the trust fund is of having its contributions suspended,” Yentel said.

Infrastructure and EB-5

One of the biggest real estate policy issues on Washington’s docket is the massive public infrastructure plan Trump has been dangling.

On the campaign trail, Trump said he wanted Congress to authorize a $1 trillion plan to improve the nation’s bridges, roads, tunnels, airports and other public infrastructure, like electrical grids.

“We’re talking about a very major infrastructure bill of a trillion dollars, perhaps even more,” Trump said last month.

Details have been scant since he’s taken office.

Before he was elected, his economic advisers released an infrastructure plan that relied mostly on incentivizing private investment. His administration is reportedly considering up to $200 billion in federal spending along with tax breaks, MarketWatch reported.

While doing something about infrastructure, in the most general sense, is one point of bipartisan agreement, Democrats largely want the $1 trillion to come from the government, not private investors.

Most of the real estate lobby is in favor of increased infrastructure spending.

Assuming the federal government does not fund all of the public projects, they could get a boost from another key target on the real estate lobbying agenda: the EB-5 visa program, which is up for reauthorization this year.

The 25-year-old program — which awards foreign investors green cards for investing cash in job-producing projects — is set to expire this year, though it got a last-minute temporary extension late last month. Renewing it permanently requires Senate and House approval.

But the program is controversial, to say the least. Opponents say it unfairly awards wealthy foreigners who can pay their way into the country, and argue that it’s too vulnerable to fraud and abuse.

The Obama administration proposed new regulations for EB-5 — such as raising the minimum investment threshold to nearly $1.4 million for visas from $500,000.

Those proposals have not gone over well with the industry, which is devoting time and money to push for reauthorization with as few changes as possible.

Trump has remained silent on the issue. However, his real estate scion son-in-law, Jared Kushner, now his senior advisor, used EB-5 funds to help pay for the construction of a 50-story luxury rental tower in Jersey City known as, you guessed it, Trump Bay Street. White House spokesperson Hope Hicks told TRD Kushner would recuse himself from all EB-5 matters.

The program has, of course, been a go-to funding spigot for NYC luxury real estate developers, but it’s also recently been used to help fund public projects like the George Washington Bridge Bus Station redevelopment and wireless internet infrastructure in the city subway.

EB-5 has been routinely renewed for years without substantial reforms, but a sizable bloc in Congress sees little merit in the program at all, and momentum against it has grown.

Texas Republican Louis Gohmert — an outspoken member of the House Judiciary Committee — has called for suspending the program entirely. “Give us your immoral, your degenerate, as long as they have money,” he quipped at a hearing in March. “The message is we want them in America, and we’ll give them a visa to get their money.”