For a good chunk of time, sovereign wealth funds were tripping over themselves to buy trophy Manhattan buildings — from classic prewar Midtown towers to gleaming new construction in Hudson Yards.

But those funds — the official investment vehicles of foreign countries like Qatar, Norway, China and others — now seem to be taking a breather.

“There’s definitely been a shift in the last 12 months,” said Alex Foshay, a vice chair at Newmark Knight Frank, who focuses on raising foreign capital.

“A bunch of sovereign funds don’t want to be as active on the core investment side anymore,” said Foshay, speaking by phone during a business trip in Asia.

The numbers seem to bear that out.

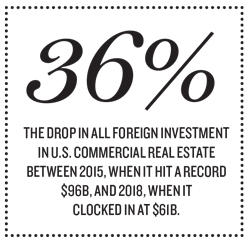

The high-water mark for all foreign investment in U.S. commercial real estate was in 2015, which saw $96 billion flow into the country, said Gunnar Branson, the CEO of A Fellowship for International Real Estate (AFIRE), a trade group whose membership includes sovereign wealth funds.

In 2018, that number plummeted 36 percent to $61 billion, he said, adding the caveat that the former number was a record.

That trend has played out locally as well.

In 2018, in all of New York City, sovereign wealth funds sold $945 million more than they bought, according to fourth-quarter numbers provided by research firm Real Capital Analytics. And 2018 was the first year to post negative net investment since 2013.

The reasons for this pullback are myriad and include everything from a soft New York market to stock market volatility to foreign instability.

In a recent survey of AFIRE members, 80 percent of participants said trade and tariff disputes were impacting — or would impact — their investing. Funds also said they expect to spend less on purchases of retail, office buildings and hotels this year.

And fund managers reported that New York is second only to London in terms of cities where SWFs expect to decrease their exposure this year.

Despite any retreat, however, survey participants still named New York the top investment target, suggesting that the city will continue to attract capital, even if from a different cohort of funds. “There’s certainly a higher sensitivity to near-term and long-term risk,” Branson said. “But there’s generally a feeling that the fundamentals are solid.”

A new day for Norway?

In 2014, four of the top five Manhattan transactions that involved sovereign wealth funds saw those funds as buyers, according to RCA.

Norges Bank Investment Management — which oversees Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global — was in on two of those deals.

That year, it teamed up with TIAA, the teacher pension fund, to buy the land under 2 Herald Square from SL Green Realty for $365 million. Around the same time, it shelled out about $1.5 billion for a 45 percent stake in three Boston Properties office buildings, including Citigroup Center at 601 Lexington Avenue.

But in 2018, four of the priciest Manhattan deals involving sovereign wealth funds were sales.

Both Kuwait and Norway led the charge.

Last December, for example, Norges and TIAA sold their entire stake in 470 Park Avenue South, a full-block office building, to SJP Properties and PGIM Real Estate for $245 million. It’s difficult to assess how Norges made out on the complicated deal, given that it bought a 49.9 percent stake in the building from TIAA in 2013 as part of a five-building, multicity acquisition, for about $600 million.

The fund — which is valued at about $990 billion — has struggled lately.

It posted a negative return of 6 percent last year, its second-weakest performance ever. (Unlike most SWFs, Norges is notably transparent about its performance.)

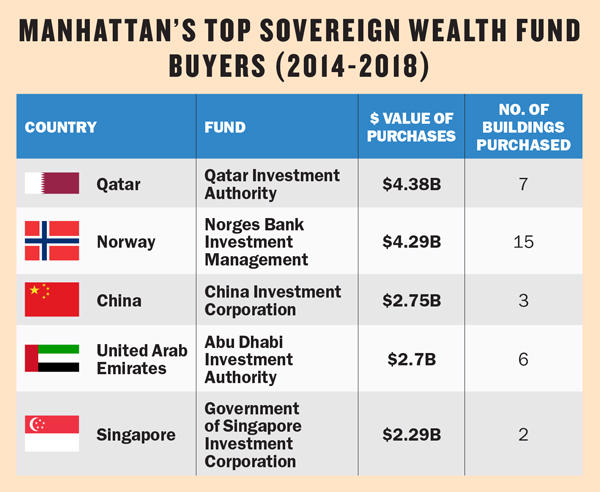

Source: Data from RCA; dollar totals include the entire value of the properties, not the fund’s stake, which is not always publicly available.

But that setback seems to have been fueled mostly by stock market investments, which were partly offset by real estate bets that logged an 8 percent profit last year, according to its annual report.

Still, in Norway, some have criticized the fund for making overly risky investments and for its reliance on buying high-profile skyscrapers. That pushback seems to have prompted a strategy shift. This past winter, the fund announced that it would spend less on nonpublicly traded real estate while eliminating a property management arm established in 2014. Real estate will now account for no more than 5 percent of investments, versus 7 percent previously, according to news reports.

“I think they are still in a period of trying to figure out what they are and what they are doing,” said a real estate executive who is familiar with the New York-based real estate operation.

The team, sources said, has about a dozen people at 505 Fifth Avenue, where Norges leases three floors. Overall, it has 600 employees in 35 nations, according to a recent LinkedIn job posting.

While calls to the fund’s New York and Oslo offices were not returned, some of its latest moves suggest it’s not backing away from New York altogether.

This spring, Norges made an even deeper commitment on an existing deal with Trinity Real Estate involving a 12-building Hudson Square portfolio. Its relationship with Trinity dates back to 2015, when it took a 44 percent stake in most of that portfolio for 75 years for about $1.6 billion. But last month, it forked over another $98 million to stretch the term to 99 years.

“Fact is, in the case of all of these sovereign funds, their home markets are too small to take on the scale of real estate investment that the funds need to put out,” said Newmark’s Foshay. “That is the central reason why they are driven to allocate investments in offshore markets.”

Taking money off the table

Norway it isn’t the only country selling Manhattan properties.

In fact, Kuwait has unloaded even more, selling its stake in two properties between 2014 and 2018.

Last spring, Kuwait — which invests in real estate through Kuwait Investment Authority, Kuwait Finance House and Wafra (all SWFs) — sold a portion of a 20 percent stake in 10 Hudson Yards that it owned with partners for $432 million.

Last spring, Kuwait — which invests in real estate through Kuwait Investment Authority, Kuwait Finance House and Wafra (all SWFs) — sold a portion of a 20 percent stake in 10 Hudson Yards that it owned with partners for $432 million.

While it’s unclear how the Kuwait Investment Authority — which has owned its undisclosed share since 2013 — did on that deal, RCA notes that based on the share sold, the entire tower would have priced at $2.2 billion in 2016. (KIA and other investors also sold a 44 percent stake in the property for about $420 million that year.)

Related Companies, which developed the tower and has a longstanding relationship with KIA, declined to comment.

Meanwhile, last year, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), a sovereign wealth fund, along with its partner, Madison Marquette, sold the retail condo at the Edge condo in Williamsburg. Gazit Horizons paid $47 million for the property, slightly more than the $45.5 million the ADIA and Madison paid in 2013.

More significantly, the Abu Dhabi Investment Council, another investment arm of the Abu Dhabi government, sold a 90 percent stake in the Chrysler Building to RFR Holding for $150 million, taking a massive haircut on the $800 million it paid a decade ago. The ADIA did not return calls for comment, but it’s also reportedly shopping around its 75 percent interest in the 39-story 330 Madison Avenue.

Related: Abu Dhabi’s albatross

Brokers, landlords and lawyers say taken together, all of these SWF sales point to the fact that foreign investors see the commercial real estate’s peak in the rearview mirror. “It’s a red flag in the sense that they believe the market is topped out,” said Lawrence Longua, a former real estate banker who now teaches at Fordham University. “They’re taking their money off the table and going home.”

In some cases, global unrest and foreign affairs have been at play.

While much attention has been paid to private Chinese companies — including Anbang Insurance Group and HNA Group — that have faced capital controls at home since late 2016 and been forced to sell real estate, the country’s chief sovereign wealth fund has received less scrutiny.

But the fund, the China Investment Corporation, which was involved in Manhattan purchases totaling $2.75 billion from 2014 to 2018, has indeed pulled back.

In 2016, CIC — which was founded in 2007 and has about $800 billion under management — made two blockbuster purchases: a 45 percent stake in 1221 Sixth Avenue for $1.03 billion and a 49 percent stake in 1 New York Plaza (with Invesco Real Estate) for $684 million.

But as Bloomberg reported last month, the fund has a new chair and has eaten losses on non-real estate investments in the last few years. A message left with CIC’s Park Avenue office was not returned.

Source: Data from RCA; dollar totals include the entire value of the properties, not the fund’s stake, which is not always publicly available.

More broadly, China’s capital controls are driving private Chinese capital out of the New York market.

Last year, HNA, for example, sold its stake in 1180 Sixth Avenue for $305 million and unloaded 850 Third Avenue for $420 million.

“Beijing asked HNA to deleverage, and you don’t not listen when mother speaks,” said Norman Sturner, a co-founder of MHP Real Estate Services, which partnered with the firm on both 1180 Sixth and 850 Third.

“You always have to be careful when dealing offshore,” added Sturner, who has approached SWFs about partnering over the years.

Scuttling scandals

In the last few years, the sovereign wealth world has suffered several black eyes.

In addition to Abu Dhabi’s unprecedented loss at the Chrysler Building and the Chinese capital controls — during which time several Chinese CEOs mysteriously disappeared — there was also the high-profile scandal involving Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund.

Since 2015, when the scandal involving that fund, dubbed 1MDB, was uncovered, a whiff of corruption has hung over the SWF world, New York brokers say.

The scandal — which centered on the prime minister allegedly embezzling funds, but also involved Malaysian fugitive Jho Low, who allegedly used stolen IMDB funds to buy high-profile New York City real estate and other assets — has highlighted the amount of discretion some have over how these funds are deployed, lawyers say.

Still, scandals aside, sovereign funds are incentivized to invest.

“You really don’t want the queen of England to have to sign a tax return,” said Daniel Kolb, a partner at the law firm Ropes & Gray, who works with several funds. “The idea is basic respect.”

Under the Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act — passed in 1980 partly in response to fears about Japanese takeovers of U.S. businesses — funds don’t have to pay taxes if they hold less than 50 percent of a building. That explains the abundance of minority positions. (Funds are subject to a number of other taxes.)

In addition, defining sovereign wealth funds has become trickier.

By many measures, they are deep reserves of money obtained from the sale of resources such as oil or natural gas and invested in real estate, stocks and bonds. But there are also hybrid funds that include profits from private companies and financial backing from governments. Similarly, a company like Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, which is backed by the Saudi Arabian government, has elements of both a venture capital and sovereign wealth fund.

Operationally, sovereign funds can be more hands-off than traditional institutional players, even though they often hire New York-based advisors, said Enrique Alonso, an executive vice president at SJP.

In 2015, SJP sold a 45 percent stake in 11 Times Square to Norges for $630 million.

“When we brought our minority interest to market, we heard from some very large institutions and some sovereign wealth funds. There was a lot of interest from Asia at the time, and Germany as well,” Alonso said. “For core assets, that time was close to the peak of the market — if not the peak.”

“Since then, there has been some pullback, especially with the Asia sovereigns,” Alonso added.

In 2018, SJP’s partnership with Norway bore more fruit when Norges began marketing its stake in 470 Park Avenue South. SJP quickly jumped in to buy it, Alonso said.

But while sovereign wealth funds may no longer have as large an appetite for trophy towers, it doesn’t mean they’re abandoning New York.

For starters, they have billions of dollars of property here. The top five sovereign wealth funds in New York own about 31.3 million square feet (much of it with partners). But in many cases, funds are taking on the role of lender and refinancing property, said Dustin Stolly, a Newmark vice chair. “From our perspective, there is much thinner demand for core trophy assets than value-add plays,” Stolly said.

They’ve also grown increasingly interested in indirect ownership, including through buying stock in real estate investment trusts like SL Green and Vornado Realty Trust, said Doug Harmon, a chairman Cushman & Wakefield, who has worked with several funds.

“The game has become more efficient, more professionalized and more institutionalized,” Harmon said, “[It’s] no longer cowboy country.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority sold its stake in the Chrysler Building. It was the Abu Dhabi Investment Council that sold the stake.