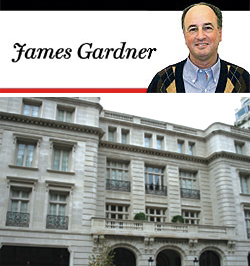

The new Ralph Lauren store on the corner of Madison Avenue and 72nd Street

It is always a good sign when a new structure has the power to astound you to the point of momentary disbelief. Please believe that my credulity was severely strained a few weeks back when I first set eyes on the new Ralph Lauren flagship at 72nd and Madison.

I do not refer to that frilly French chateau on the southeast corner, the famed Rhinelander Mansion, which has occupied that spot for more than a century and has been a Ralph Lauren flagship since 1984. Rather, I refer to an entirely new structure that now presides over the southwest corner of the avenue.

I have been walking by this parcel of Manhattan for decades, and for the longest time I was dismayed that it was occupied by nothing grander than a two-story taxpayer structure. The original building went up about eighty years ago, but with Manhattan real estate in a state of near incandescence for at least a generation (even including the recent downturn), I always wondered why no one thought to do more with this corner of the city.

When Ralph Lauren opened a men’s boutique in the building, he freshened the place up, but he did little to address the underwhelming, underachieving essence of the site. So I did not expect much when, about a year and a half ago, the two-story building was razed. Some boards went up around the site, and above them you could see a steel skeleton starting to rise up earlier this year, but still I expected nothing.

Then I went on vacation for a few weeks in August; when I returned at the end of that month I was quite literally flabbergasted to find myself standing before a large and fully fledged French palace that appeared to have come out of nowhere. To repeat: There had been nothing there, and suddenly there was something mightily substantial, as sturdy in its forms and structure as the Metropolitan Museum, the New York Public Library or City Hall.

This brand-new building is by the relatively young firm of HS2 Architecture (together with Weddle Gilmore, of Arizona). Apparently there had been some initial talk of building a modernist affair on the site, and HS2 Architecture’s previous projects, largely spare and minimalist in aesthetic, would have made them quite suitable. But after the locals expressed opposition to anything too obviously modern, and after discussions with Lauren himself, famously a defender of traditionalist tastes, it was decided not only to build a more classical structure, but also to pull off one of the most extravagantly historicist stunts of the past decade.

HS2 had been the firm behind Julian Schnabel’s bubblegum-pink high-rise at 360 West 11th, but it had little experience in this Beaux Arts style. And yet they have acquitted themselves so well, in collaborating with the Ralph Lauren design team, that the resulting structure looks as though it has been there since the 19th century.

Ralph Lauren store on the corner of Madison Ave. and 72nd St.

The only giveaway that it is a new structure is the fresh, even pristine, look of the Indiana limestone facing. Presumably when it has weathered one or two New York winters, it will look like many another august structure in the city, but for now the details are as sharp as anything. It is instructive to think that this is what many classical structures of old, from the east facade of the Louvre to the 42nd Street Library, looked like when they were newborn.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the building is that, although it corresponds with certain elements of New York architecture from the end of the 19th century, it feels, in a profound sense, as though it had been hatched in Paris. The rusticated arches at street level, as well as the volute scrolls that link those arches with the balustrade balconies on the second floor, look like some quintessentially Beaux Arts building on the Boulevard Haussmann. True, the building’s classical vocabulary can find precedents at various points along Madison Avenue. But the size and grandiosity of the new store cause it to seem like a far more weighty project. Indeed, even though it is roughly the same size as the Rhinelander Mansion directly across the street, to this observer it bulks much larger, and appears to be much more powerful.

Occupying one of the cardinal corners of the avenue, the new building rises four stories. Its longer side, on Madison, consists of two diminutive wings that flank a central area comprising three arches. The corners of the building are curved, with rusticated coigns, those architectural markings that surround the corners. Over the arches is a balcony, above which are three slightly recessed stories.

That recession is the only part of the design that does not work entirely to my satisfaction. As for the rest, it is fastidiously correct according to the canons of 19th-century architecture. On the second floor the windows, topped with austere lintels, are graced, after the Parisian fashion, with brass and wrought iron. Between the third and fourth stories there is a pronounced cornice, decked out in a refined dentilated motif that looks back ultimately to the Parthenon. Above the cornice, the top story is itself crowned with a balustrade along most of its length. Another nicely Parisian touch, on either side of the main entrance, is a pair of sumptuously wrought iron lanterns, reminiscent of the streetlights on the Place VendÙme.

The 72nd street facade is more sober than the one on Madison, and works even better. Especially pleasing is the way the rustication at the corners yields to serene fields of smoothed stone around the windows, thus emphasizing the inherent loveliness of the material and reminding us of why it has been used to build so many banks and state capitols. The new Ralph Lauren store is the shadow of a shadow: It is a canny and scrupulous reenactment of the sort of Beaux Arts buildings of the turn of the last century, which themselves were imitations of the French high-classicism of such 17th-century architects as Le Vau and J.H. Mansart. And that architecture was itself, of course, a reinterpretation of ancient Greek and Roman models.

No one should pretend, therefore, that the new arrival on 72nd street answers to the highest or purest ambitions of architecture, any more than did its late-19th-century models (the 17th-century sources are certainly a different matter). But what now occupies that crucial corner of Manhattan is infinitely better than what it replaced. And anyone who has frequented this part of the city over the past few years or decades should feel devoutly grateful that the area has now been so materially improved.