Everyone knows, if you want to save money, buy in bulk. With prices for condos and co-ops in the stratosphere, bargain hunting these days is a challenge. But some investors have hit on a creative way to find value-priced properties: Buy multiple units in a single building.

The market for bulk-unit packages is a modest portion of New York real estate, data reviewed by The Real Deal shows. It can be difficult to track, and fluctuates widely, largely because with a market this small, one or two large transactions can skew the results, TRD’s analysis found.

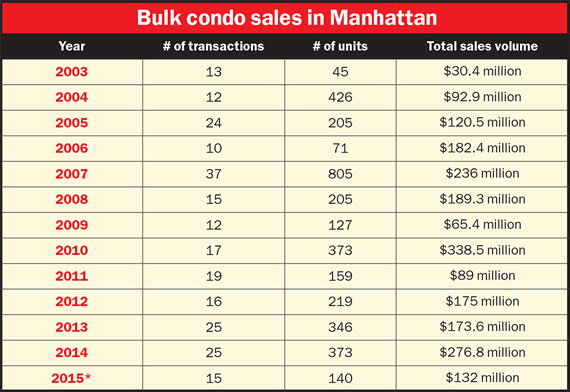

For instance, just 45 units traded in bulk packages in 2003, with 13 transactions totaling $30.4 million, according to city Department of Finance records.

Then, the numbers started a steady climb, reaching a total of $236 million involving 37 deals for 805 units in 2007.

After dropping off in 2008 and 2009, likely reflecting the market turmoil during the financial crisis, they spiked in 2010 to their highest total volume in recent years, $338.5 million for 373 units in just 17 transactions.

Bulk sales dropped back the following year, and since then, have been erratic, though generally rising.

Total bulk sales reached around $277 million in 2014, on 373 units sold in 25 transactions, TRD’s review found.

In the first seven months of this year, $132 million in bulk properties moved, encompassing 140 units in 15 transactions. While the annual fluctuations make it hard to predict what the full year’s totals might be, it’s worth noting that in 2014, two thirds of bulk transactions took place in the second half of the year.

Big deals

Unsurprisingly, a handful of big-ticket deals can dominate this portion of the market.

Source: New York City ACRIS records; *2015 figures based on sales for January through July. (Click to enlarge)

One such transaction occurred in June, when the Moinian Group sold a package of 32 condo units at the W Downtown for $27 million to the San Francisco-based American Pacific International Capital, a firm that deploys Chinese capital. That’s just over $840,000 each, or a 35-to-40 percent discount per unit, compared with two purchases at the property for $1.3 million and $1.4 million in the days before the bulk sale. Sales in the mixed-use tower, where the conversion started in 2006, struggled during the recession, though they picked up by the time the last block was sold off. The block was leased to a management firm for use as extended-stay hotel rooms through 2016.

By far the biggest deal in recent years took place in August 2014, when Gaia Real Estate bought 144 units at the Corinthian condo building in Murray Hill from Eliot Spitzer’s Spitzer Enterprises, paying $147 million, or about $1.02 million per unit. In the week preceding the sale, units at the building went for just under $1 million to $1.2 million, meaning Gaia paid a premium on some condos, but got a discount up to about 15 percent on others.

Gaia’s high-end purchase price was roughly equal to the typical discount for such large packages, but they are sometimes as low as 2 or 3 percent, according to Robert Knakal, chairman of New York investment sales at Cushman & Wakefield, who represented the seller in both the W Downtown and Corinthian deals.

In both, the sponsors sought to unload the remaining unsold units in relatively new buildings, Knakal said. At the Corinthian, Spitzer’s firm had been renting out the units since 1988, a year after his father, Bernard, developed the building. It was one of the first deals Spitzer handled since he returned to the real estate business, and was seen by some as a way to finance his foray into development in Brooklyn.

Knakal said both deals made sense for the sponsors.

The advantage, he said, in addition to fast cash, is “tremendous economies of scale.” For example, selling in bulk significantly reduces transaction costs, like legal and broker fees.

Knakal noted that residential brokers usually make a 5 or 6 percent commission on condo and co-op sales at buildings like the Corinthian and the W Downtown, whereas his commission on the sales, percentage-wise, was just “a fraction” of that.

Sponsors also save time, which, as the aphorism states, is money too.

“Just imagine how long it would take to sell 144 units, one-by-one,” said Knakal. And sellers may be able to make up some of the discounted price through tax savings. That’s because, Knakal noted, sponsors are often able to claim their income from these deals as capital gains, rather than earned income.

Such a claim amounts to a 15-to-20 percent lower tax rate, according to Richard Wolfe, tax partner at Fried Frank’s New York office.

“That gets most people’s attention,” he said.

Wolfe explained that unlike sellers of individual condos and co-ops, bulk sellers who own the properties for more than a year — especially those renting the units prior to the sale — can often argue that the units amount to income-generating investments, and therefore any profit from their sale counts as a long-term capital gain.

The legal standard centers on the seller’s intention, which is difficult to determine, allowing for wide latitude on capital gains claims.

Nice if they can get it

For buyers, said Knakal, the appeal is strong cash flow from renting the units, along with the possibility of obtaining a critical mass of properties in a particular building, granting negotiating power over future sales and potential conversions there.

Bulk buyers of condos and co-ops who choose to rent the units can usually charge higher prices than at comparable rental buildings, as the condo and co-op buildings in question are often relatively more luxurious and better maintained.

And bulk buyers can also easily cover their costs or exit their positions by selling individual units.

Knakal said he was aware of two deals in the works, both in newly constructed Manhattan buildings, one worth around $100 million and the other around $60 million.

“You would think it would happen more frequently,” said Knakal.

Robert Knakal

The reason it doesn’t, he said, is that in a strong market, sellers see little reason to take any discount at all, especially when they also have the option to rent the units.

Potential sellers also fear competing against bulk buyers, who could easily turn around and put the units back on the market. That’s why condos traded in bulk are almost always the last units available in their buildings.

As a result, these kinds of large, high-end transactions are relatively rare. Since 2013, TRD research found only 11 transactions over $10 million.

“Companies like ours don’t usually want to do it,” said Gaia co-founder and managing partner Danny Fishman.

The main reason, he said, is the necessity of dealing with condo and co-op boards. “In most cases, they are not happy that there is one big buyer that holds a big block of units,” said Fishman.

He said condo owners, having left the rental world, are also generally averse to developers letting out units in their building.

But, said Fishman, “When we work with them, they find we have the same interests: to upgrade the building, to reposition the building. We bring expertise. We renovate the building, and advertise. They see a lot of improvement. Their property value is going up, and we’re exiting as well.”

Fishman said this was Gaia’s plan for the Corinthian units. The firm hired architect Andres Escobar, changed unit layouts, combined some, and pushed the board to upgrade the building’s hallways and lighting.

Today, 30 percent of Gaia’s Corinthian units are either sold or in contract. Fishman said the firm plans to move the remaining units in the next 12 months.

Rent-stabilized units

The vast majority of bulk sales are smaller, usually under 10 units in a building, and sometimes as few as four or five.

In these sales, the circumstances are typically quite different. One common scenario involves a rental building converting to condos where a number of tenants refuse to move out. The developer undertaking the conversion will often sell these units in bulk, typically to one of a relatively small group of buyers who specialize in managing such properties.

“We used to call them ‘hairy deals’,” because they come with “hair” in the form of rent-regulated tenants, who can complicate owning the property, said developer Myles Horn.

Horn has been trading bulk units since the 1970s, moving over 5,000 units, including his purchase in 1999 of a massive 627-unit package from the Helmsley family, for which he spent almost $36 million in today’s dollars.

He said he buys units both from conversion sponsors and from the lenders who sometimes foreclose on them. His current holdings total about 200 units in 12 buildings, after he recently sold off 60 units in the Printing House, a condo conversion in the West Village, and 30 more at Continental Park, a co-op conversion in Elmhurst, Queens.

A model unit at the Printing House in the West Village

In the old days, Horn said, he would pay as little as 15 cents on the dollar for bulk packages of rent-regulated units. Today, they go for 25 or 35 percent of market value, and sometimes into the 40 percents in ritzier buildings.

Horn said the reason for the deep discounts is that the units frequently generate negative cashflow. In many cases, he explained, the rent the tenants paid for units he bought was lower than the condo or co-op fees he, as owner, was obligated to pay.

He makes his money by “accelerating vacancies,” he said. While he learns all he can about the tenants and is willing to leverage situations in which tenants are violating their lease in any way — illegal subletting, for instance, or falsely claiming the units are primary residences — generally the process is “all business.”

Contrary to images of “people coming in the middle of the night to bang on pipes,” Horn said, nearly all the acceleration comes in the form of negotiated buyouts, discounted purchases by tenants or subsidized relocations.

With a large enough portfolio, Horn said he can “let the actuarial tables do their work,” and predict relatively accurately how many units will become vacant, either through deaths or tenant relocations, over a given span of time.

He also makes money by improving the finishes and amenities of the buildings in which he buys, sometimes with the help of co-op boards or other condo owners, in much the same way Gaia did at the Corinthian. He is then able to raise the value of his units, and, ultimately, their sales prices.

“Usually, they’ve seen better days,” he said of the properties he buys.

Horn funds his purchases through relatively high-interest loans, most often for a term of three years, which he says is usually enough to cover his costs. “I’ve learned that if you pay a bank enough money, they’ll make you a loan.”

In decades past, only a very small number of developers and investors — Horn said between six and 12 — played in this market. But in the last few years, “usurpers” have entered the space seeking bargains, increasing competition, driving up prices and in general, Horn said, “muddying up the works.”