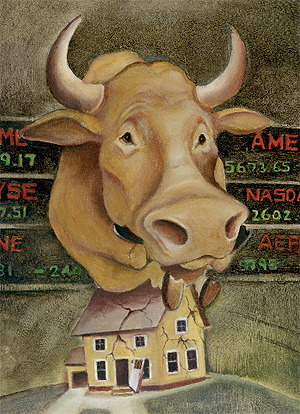

Cover artwork by Squat Design

In its eight years of publication, The Real Deal has covered the real estate industry in a city that’s been transformed by a massive building boom, was crippled by the subsequent bust, and is now in the midst of a tentative recovery.

The compendium of stories we’ve written runs the gamut from the record-setting building and apartment purchases during the boom, to the toppling of mega-developers during the bust, to new entrepreneurs trying to get into the real estate game during today’s fragile recovery.

We have also combed through data for dozens of lists, ranking everything from top Manhattan residential brokers and firms to top commercial firms — including for office leasing, building sales and retail leases — as well as the biggest real estate lawyers and the most active REITs.

And, for those who can’t get their fill of real estate statistics, we’ve been putting out our annual Data Book since 2006, which is stuffed with real estate numbers too.

This month, for the anniversary of our 100th issue, we bring you some of the most compelling stories we’ve tracked in these pages, many of which have unfolded and evolved over time, much as the magazine itself has. (The magazine started in Publisher Amir Korangy’s then-Prospect Heights apartment with just two full-time staffers, and now operates out of a full floor on West 29th Street with 25 full-time employees and dozens of additional freelancers.)

The cast of real estate characters that we’ve chronicled since we launched is comprised of colorful, larger-than-life figures who have made their marks on the New York skyline in profound ways. They include the likes of real estate players such as Harry Macklowe, Donald Trump, Steven Roth, Stephen Ross, Costas Kondylis (whom The Real Deal also just released a documentary film on), the Zeckendorf brothers, Aby Rosen, Mary Ann Tighe, Robert A.M. Stern and scores of others.

The amount of money involved in some of the transactions that the magazine has covered is staggering. Of course, there was the $5.4 billion Stuyvesant Town sale, a record for a single real estate asset, and Google’s $1.77 billion purchase of 111 Eighth Avenue, the priciest building sale last year. In 2007 alone there were a record $48.5 billion in Manhattan investment sales that traded — which dropped to just $3.5 billion in 2009 and rebounded to $13.6 billion in 2010. Dissecting complex deals where the stakes are high and the structure is complex is what makes covering New York real estate so thrilling for us.

Plus, in the almost decade that we’ve been plugging away, the real estate DNA of neighborhoods across the city has drastically morphed. Indeed, the crush of new construction, in places like Williamsburg and Chelsea, offers ever-changing examples of the city’s constant reinvention.

While our focus is always on the real estate — whether it be how a property is financed, how many units have sold or how distressed properties are getting worked out by a lender — our coverage also chronicles some of the enormous changes New York has experienced over the past several years. Here’s a look at some of the stories that have made the greatest impact.

The Time Warner Center — a former no-man’s-land

The Time Warner Center transformed Columbus Circle when it opened in 2004.Nearly eight years ago, prior to the opening of the Time Warner Center, an article in The Real Deal characterized Columbus Circle as a former no-man’s-land for retail, noting that one of the aims of the Related Companies’ $2 billion complex was to turn the area into a destination address. The development was the largest in the United States at the time, and the largest in New York since the World Trade Center was constructed. “Until it is open, I don’t think people will understand the importance of the project,” Related head Stephen Ross told The Real Deal in a 2003 interview. The project did succeed in making the area a destination, and proved that a high-end, vertical shopping center could thrive in Manhattan (see “The ‘malling’ of Manhattan”). By early 2005, 90 percent of the 325,000 square feet of retail space was leased to tenants like Whole Foods, Tourneau, Sephora and Williams-Sonoma. The complex’s Mandarin Oriental hotel, Jazz at Lincoln Center, and well-regarded restaurants such as Per Se also lured consumers to Columbus Circle. Meanwhile, the condominiums at the Time Warner Center became some of the most expensive in the city, attracting celebrity buyers, including NFL quarterback Tom Brady and music superstars Ricky Martin and Jay-Z.

Michael Shvo: over the moon to off the map

Michael Shvo during his real estate prime in 2006A couple of months before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Michael Shvo was reportedly having his interns compete to design the first residential property on the moon. By the middle of 2009, however, the broker who embodied the heights — and, to his critics, excesses — of Manhattan’s real estate boom had all but disappeared from New York. (The Real Deal‘s 2009 piece “Where in the world did Shvo go?” looked at how the Israeli émigré fled the limelight.) Shvo started in the industry at Prudential Douglas Elliman and quickly became one of the firm’s top-grossing brokers, bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. He left Elliman to start his own firm in 2004; at the time, the 31-year-old told The Real Deal that his company would be “the young, happening thing.” Shvo did indeed go on to create happenings at the condos he marketed. The launch of the Philippe Starck-designed Gramercy had burlesque dancers, and the opening of 20 Pine, with interiors designed by Armani Casa, featured a performance by John Legend. Shvo also lived the high-flying lifestyle he marketed, purchasing numerous multi-million-dollar pads. Along with buzz came enmity, though: There were murmurings in the industry of unethical behavior, and other brokers didn’t hide their contempt for his flashy persona and tactics. In the past couple of years, trouble has plagued a number of projects Shvo marketed, including Rector Square, the first occupied condo in the city to enter foreclosure. Shvo declined to comment on which, if any, developments he is currently marketing.

Manhattan hits million-dollar mark

In 2004, Manhattan real estate reached a new high-water mark when the average price of an apartment hit more than $1 million for the first time, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel. Prices kept going up until the market peaked in 2008, when the average hit $1,591,823 and the median sale price for the year was $955,000. While prices peaked in 2008, the effects of the credit crunch were discernible even before the financial crisis in September: Apartment sales declined every quarter, and totaled 10,299 at the end of the year, down from 13,430 the prior year. In 2009, prices declined an average of 25 percent from the market peak. Since then, there have been some signs of recovery. The average Manhattan price in the fourth quarter of 2010 was $1.482 million, which represented a 14.4 percent year-over-year increase. At the time, however, appraiser Jonathan Miller told The Real Deal that “prices are flat across the board,” and the increases reflected that more of the properties that sold were larger apartments. Still, Miller noted that the “two-year roller coaster of housing trends because of financing and credit” could be over, as sales volume and available inventory at the end of 2010 were in line with 10-year averages. But credit is still incredibly tight. In the second quarter of this year, the average and median sale prices were $1.455 million and $850,000, respectively, indicating a stable but uninspiring market that Miller characterized as “bumping along the bottom.”

Rezonings pave the way for more towers

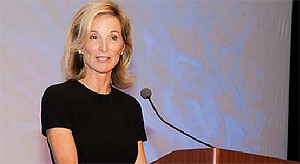

Amanda Burden, the chair of the Department of City PlanningOne of the biggest moves by the Bloomberg administration since The Real Deal‘s launch has been the creation of thousands of units of housing by rezoning large swaths of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens to allow for residential development. As a result of these rezonings, some neighborhoods were completely transformed in the aughts. In Chelsea, rezonings paved the way for construction of high-rises along Sixth Avenue between 24th and 31st streets; the stretch, which had been defined by small commercial buildings and parking lots, saw heavy development in the form of towers such as the Chelsea Landmark and Chelsea Stratus. In the Far West section of the neighborhood near the High Line, a later rezoning gave birth to more than a dozen condo projects, including the Caledonia and 100 Eleventh Avenue. In Brooklyn, no area was changed more than Williamsburg-Greenpoint following a 2005 rezoning: Condo towers like the Edge and Northside Piers were built on the formerly industrial area along the waterfront, and dozens of smaller condos were constructed further inland. While the city hoped the rezoning would result in 10,000 new housing units, many projects stalled following the bust in 2008, and in 2009 the Bloomberg administration said only 1,800 units had been built or were under construction. In Queens, Long Island City became a locus of development following a 2001 rezoning; in 2005, The Real Deal reported that 11,550 units of housing were planned for the industrial area. As in Williamsburg, many of those projects failed to come to fruition, but dozens of new buildings, including high-rises on the waterfront developed by Avalon Bay and Rockrose, did see the light of day.

Stuyvesant Town’s mega-sale makes waves

A view of Stuy Town, which sold for $5.4 billion in 2006 Developer Tishman Speyer and investment firm BlackRock purchased mega apartment development Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village for $5.4 billion from MetLife in 2006. It was the biggest real estate deal in U.S. history and, of course, one of the biggest stories to hit since The Real Deal‘s inception. The record-breaking sale of the 11,232-apartment complex, at the height of the city’s real estate boom, was predicated on the notion that the new owners could turn much of the property’s rent-regulated stock into market-rate apartments. The market-rate conversions were slow to materialize, however, and tenants’ groups wound up being victorious in a lawsuit, which charged that MetLife and the new owners had improperly deregulated thousands of apartments. By the middle of 2009, it became clear that the heavily leveraged investment was troubled and, in early 2010, after missing a $16 million loan payment, Tishman Speyer and BlackRock announced they were turning the property over to their creditors to avoid bankruptcy. CWCapital, which represents the holders of the $3 billion first mortgage on the complex, took control of the property late last year, following a failed attempt by hedge-funder Bill Ackman and Winthrop Realty Trust to win control of the buildings by purchasing $45 million in subordinate debt. The tenants’ association and CWCapital have since discussed turning Stuy Town into an affordable co-op. Last year, the special servicer representing CWCapital valued the property at $2.8 billion.

Records shatter during boom

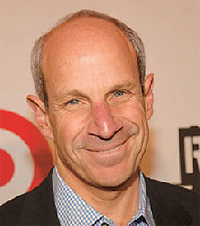

Jonathan Tisch

During the boom years, one real estate record after another was shattered. In 2003, the GM Building became the most expensive building sold in North America when Macklowe Properties bought it for $1.4 billion, only to be surpassed by Kushner Companies’ purchase of 666 Fifth Avenue for $1.8 billion in 2006. The 2006 sale of Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village for more than $5 billion, meanwhile, was the largest single asset sale in U.S. history. The residential real estate world also saw plenty of jaw-dropping deals. Developer Harry Macklowe (who sold the GM Building in 2008 to pay off mounting debts) made headlines when he paid $51.5 million for a combination of seven units at the Plaza in 2007. That was the most money ever spent on a condo. In 2008, the record for the biggest co-op sale was set three times: first when hedge fund manager Scott Bommer paid $46 million for a duplex at 1060 Fifth Avenue, then when Loews Hotels CEO Jonathan Tisch paid $48 million for a unit at 2 East 67th Street, and again when Bommer sold off the co-op he’d acquired months earlier for $48.9 million. In 2006, the biggest home sale ever in the city was notched when investor J. Christopher Flowers paid $53 million for the Harkness Mansion at 4 East 75th Street. Last month, Flowers reportedly sold the mansion for $16.5 million less than he paid for it.

The Apthorp saga

Lev Leviev In 2006, developer Maurice Mann partnered with diamond billionaire Lev Leviev’s Africa Israel to purchase one of the city’s grandest apartment buildings, the Apthorp, on Broadway and 79th Street. The team paid $426 million, and planned to convert the Apthorp, where half of the 163 apartments were rent stabilized, into condos that were expected to sell for a combined total of more than $1 billion. What followed instead was a protracted drama involving lawsuits, changes in marketing teams, and sales that didn’t come anywhere near initial forecasts. In late 2008, the property was threatened with foreclosure; Mann filed suit against the lender, but, facing litigation from Leviev, agreed to step down as a managing partner of the conversion. The Prudential Douglas Elliman marketing team raced to sell 25 units at the building by September 2009 so that the conversion could be declared effective by the Attorney General’s office, bringing in superbroker Dolly Lenz, and closings finally began in mid-2010. In August 2010, The Real Deal reported exclusively about a so-called lockbox agreement whereby tenants at the building would send rent payments directly to Anglo Irish Bank, rather than to the building’s owners. A few months later, in the fall of 2010, Lenz severed ties with the developers, citing unpaid commissions and mismanagement, and the Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group replaced Elliman as the building’s exclusive managing agent. Meanwhile, throughout the conversion process, longtime tenants repeatedly complained about the renovation work, and the building racked up dozens of violations with the city. As of June, Corcoran was reporting that average sales prices in the building were $2,000 a foot; original prices were set at around $3,000 a foot. The firm also reported that 25 percent of the units in the building had sold.

Breaking down buyers at 15 Central Park West

When Arthur and William Lie Zeckendorf purchased the site where 15 Central Park West would rise for $401 million in 2004, some gasped at the price the developers paid. The Zeckendorfs ended up having the last laugh, though, as the condo turned out to be the most successful in history, bringing in $2 billion in sales for the developers by the time it sold out in 2007, from buyers attracted to Robert A.M. Stern’s Neoclassical design. While the limestone-clad development on 61st Street was a throwback to the ’20s, 15 Central Park West’s amenities — including a health club with a 75-foot swimming pool, a screening room, wine cellars and an in-house chef — were of this millennium. In 2008, The Real Deal peeled back the curtain on the building with a unit-by-unit breakdown of the first wave of buyers, the most famous of whom were actor Denzel Washington, Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein, and pop musician Sting. The most expensive unit sold at that point — and, at the time, the most expensive condo to ever sell in a New York building — was a 10,674-square-foot penthouse that hedge fund manager Daniel S. Loeb bought for $45 million. The building has continued to command high prices in resales: William Lie Zeckendorf sold his personal penthouse there for $40 million last December, a deal that worked out to a jaw-dropping $10,000 a foot.

Harry Macklowe: down, out and back again

Harry Macklowe No developer gambled on real estate during the boom like Harry Macklowe, and no other developer sustained losses as spectacular. In 2003, Macklowe paid $1.4 billion to buy the GM Building, a record-breaking purchase that was eclipsed a few years later by his $7 billion acquisition of seven Midtown office buildings from Sam Zell’s Equity Office Properties. The latter investment went south in 2008, when Macklowe defaulted on a $5.8 billion loan associated with the deal, and lenders assumed control of the buildings. Later that year, Macklowe, whose every move has been chronicled by The Real Deal and other real estate publications, was also forced to sell the GM Building and three other towers to Boston Properties for $3.9 billion. In 2010, meanwhile, Macklowe sold three apartment buildings to Zell for $475 million. His son, Billy Macklowe, severed professional ties with him the same year. While Macklowe saw the lion’s share of his portfolio disappear, he has recently been staging what could turn out to be a comeback: Although he sold the Drake Hotel development site to the CIM Group last year, he is still said to be a partner with CIM on plans for the site. Meanwhile, he purchased 737 Park Avenue for $360 million this year, and last month filed plans with the AG’s office to convert the rental into condos in another partnership with CIM. If the offering plan is approved by July 2012, closings could begin at the Upper East Side properties by late 2012 or 2013.

Sam Chang’s fast, cheap and ubiquitous hotel model

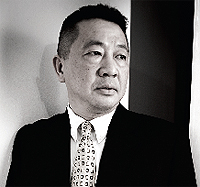

Sam Chang

What McDonald’s is to hamburgers, the McSam Hotel Group was during the boom years to hotel development: fast, cheap and ubiquitous. In mid-2008, Sam Chang, McSam’s founder, had 5,500 hotel rooms planned in the city (a sizable portion of all units underway in New York); at that point he’d built more than 30 properties. Chang — whom The Real Deal featured on the cover in December 2006 (helping to introduce him to the New York real estate world), who interviewed for “The Closing” in July 2008, and who has had countless stories written about him — brought a new business model to New York. He focused on developing budget hotels more commonly found in other parts of the country — brands like Holiday Inn Express and Days Inn — and it made him the most prolific developer of limited-service hotels in the city. The Taiwanese immigrant specialized in finding relatively inexpensive places to build, typically in areas zoned for industrial uses, and usually sold them to operators after they’d been constructed. Known for his speed, Chang would buy development parcels over the phone, sight unseen. He has said his idea of retirement would be building one hotel at a time rather than 30. By late 2009, well into the city’s development bust, Chang had reportedly built 37 hotels in New York, but plans to build more slowed as financing became more difficult to obtain. Although Chang is said to have a handful of development projects in the works at present, he’s been in selling mode lately, unloading stalled sites in the Financial District and Union Square this year. Chang did not return a call for comment.

Brooklyn’s real estate ascent

Brownstone Brooklyn real estate is trading at high volumes, despite the tentative market.

When The Real Deal started publishing, only two Manhattan-based residential real estate firms had offices in Brooklyn: Corcoran and William B. May. By the following year, 2004, Brown Harris Stevens had inked a deal to take over William B. May’s offices in the borough, and Halstead Property and Prudential Douglas Elliman had also opened Brooklyn outposts. At the time, Halstead President Diane Ramirez noted that Brooklyn offered relative affordability compared to Manhattan. But prices in prime Brooklyn neighborhoods have skyrocketed in the years since Ramirez’s statement: A $7 million sale at Dumbo’s Clock Tower Condominium set a record as the priciest condo to ever sell in the borough, while a handful of Brooklyn Heights townhouses fetched more than $10 million. In tandem, The Real Deal‘s coverage of Brooklyn has drastically evolved since those early days, as we’ve dissected the market in the borough, done a first-ever ranking of its top brokers, and written about new development from Bushwick to Brooklyn Heights. The condo boom, meanwhile, changed the landscape in areas like Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn. Still, the crush of new development meant Brooklyn was particularly hard-hit by the late-2008 crash: In October 2009, 47 percent of all stalled construction sites in the city were in Brooklyn, and prices had dropped to 2005 levels. As of this year, NYU’s Furman Center was reporting that Brooklyn prices had plummeted more than 30 percent from the market’s peak. But brokerage reports covering Brooklyn have recently indicated a generally stable sales market, with properties in the northwest “brownstone Brooklyn” trading at a high volume and posting price increases.

Lehman Brothers falls; the bulls cower

In September 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy protection, precipitating one of the worst financial crises in the United States since the Great Depression — and roiling the city’s real estate industry. The collapse prompted The Real Deal and other publications to adopt the phrases “pre-Lehman” and “post-Lehman” as shorthand for describing the market. In the aftermath, commercial and residential deals ground to a veritable standstill, stalled construction sites dotted the city’s landscape, and developers ceded condo projects to lenders. By July 2009, second-quarter market reports showed that Manhattan residential sales volume was off 50 percent from the same quarter in 2008 — a record drop. That same July, The Real Deal published a story headlined, “New lender motto: Extend and pretend,” industry lingo for lenders holding on to underwater real estate loans because they don’t want to take large, single-quarter losses. The term, which Eastern Consolidated’s Alan Miller used in the story, caught on like wildfire after it appeared in the magazine. Things have, of course, improved since then. On the residential side, prices and volume are both up substantially since 2009, but appraiser Jonathan Miller has repeatedly said the market appears to be on a “sideways” trajectory. On the commercial side, overall values are still thought to be significantly off-peak, though the market has shown signs of recovery: $13.6 billion in property traded last year, over three times what was sold in 2009, according to Cushman & Wakefield. The city began counting stalled building sites in 2009, and the number on the list last November, 710, is believed to represent the peak of the tally. Since then, construction lending has slowly returned and investors have purchased distressed assets. But as of late last month, the city still had 646 stalled sites on the list.

In September 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy protection, precipitating one of the worst financial crises in the United States since the Great Depression — and roiling the city’s real estate industry. The collapse prompted The Real Deal and other publications to adopt the phrases “pre-Lehman” and “post-Lehman” as shorthand for describing the market. In the aftermath, commercial and residential deals ground to a veritable standstill, stalled construction sites dotted the city’s landscape, and developers ceded condo projects to lenders. By July 2009, second-quarter market reports showed that Manhattan residential sales volume was off 50 percent from the same quarter in 2008 — a record drop. That same July, The Real Deal published a story headlined, “New lender motto: Extend and pretend,” industry lingo for lenders holding on to underwater real estate loans because they don’t want to take large, single-quarter losses. The term, which Eastern Consolidated’s Alan Miller used in the story, caught on like wildfire after it appeared in the magazine. Things have, of course, improved since then. On the residential side, prices and volume are both up substantially since 2009, but appraiser Jonathan Miller has repeatedly said the market appears to be on a “sideways” trajectory. On the commercial side, overall values are still thought to be significantly off-peak, though the market has shown signs of recovery: $13.6 billion in property traded last year, over three times what was sold in 2009, according to Cushman & Wakefield. The city began counting stalled building sites in 2009, and the number on the list last November, 710, is believed to represent the peak of the tally. Since then, construction lending has slowly returned and investors have purchased distressed assets. But as of late last month, the city still had 646 stalled sites on the list.

The High Line: A starchitect magnet

Annabelle Selldorf and Jean Nouvel

By the time the first section of the High Line opened in 2009, developers had already bet big on the blocks surrounding the elevated train-track-turned-park. After the city allocated funds toward greening the High Line in 2004, and rezoned nearby blocks the same year, plans for condos, rentals and hotels mushroomed. In 2005, brokers told The Real Deal that between 7,200 and 10,000 new residential units could well be built in the area within the next decade. At the height of the market, properties were reportedly trading for up to $400 a buildable square foot. Many developments were put on ice after the credit crunch — including a would-be hotel that Jay-Z partnered in. Still, a number of them designed by notable architects did get built, to the point that the area near the High Line is sometimes referred to as the “starchitecture district.” The blocks near the park include 100 Eleventh Avenue, designed by Pritzker Prize-winner Jean Nouvel; the Annabelle Selldorf-designed 200 Eleventh Avenue, which features an automatic car elevator; the Metal Shutter Houses on West 19th Street, designed by Shigeru Ban; and the Neil Denari-designed HL23 on West 23rd Street.

Developers face buyer mutiny

Real estate lawsuits surged following the financial collapse in late 2008. The squabbles pitted would-be buyers and developers — not to mention developers and lenders — against each other. Many buyers tried to get out of contracts for condos by alleging defects in new construction, missed closing dates, or inflated representations of how many units in a building had sold. In December 2009, The Real Deal‘s spread “Fighting Buyer Mutiny” looked at the 20 buildings that had the highest percentage of buyers trying to back out of their contracts, and provided a breakdown of how those cases were beginning to get resolved. Much of that coverage focused on an arcane federal law called the Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act (ILSA), which many buyers were seizing on to make their cases. ILSA requires developers to register buildings with 100 or more units with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development before contracts are signed. Lawsuits claiming that developers didn’t provide a mandated report on ILSA registration are still playing out in court, though in a closely watched case, a federal circuit court ruled this March that the sponsors of Harlem’s Fifth on the Park condo and the One Hunters Point condo in Long Island City were not exempt from ILSA regulations. And, a judge rejected a motion to dismiss a similar ILSA suit against the Moinian Group at the W New York Downtown Hotel and Residences last month.

Real estate lawsuits surged following the financial collapse in late 2008. The squabbles pitted would-be buyers and developers — not to mention developers and lenders — against each other. Many buyers tried to get out of contracts for condos by alleging defects in new construction, missed closing dates, or inflated representations of how many units in a building had sold. In December 2009, The Real Deal‘s spread “Fighting Buyer Mutiny” looked at the 20 buildings that had the highest percentage of buyers trying to back out of their contracts, and provided a breakdown of how those cases were beginning to get resolved. Much of that coverage focused on an arcane federal law called the Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act (ILSA), which many buyers were seizing on to make their cases. ILSA requires developers to register buildings with 100 or more units with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development before contracts are signed. Lawsuits claiming that developers didn’t provide a mandated report on ILSA registration are still playing out in court, though in a closely watched case, a federal circuit court ruled this March that the sponsors of Harlem’s Fifth on the Park condo and the One Hunters Point condo in Long Island City were not exempt from ILSA regulations. And, a judge rejected a motion to dismiss a similar ILSA suit against the Moinian Group at the W New York Downtown Hotel and Residences last month.

Kent Swig falls off his surfboard

While many developers have seen reversals of fortune in recent years, few have been as colorful and well-publicized as Kent Swig’s. Until a few years ago, Swig was considered real estate royalty: a prominent commercial landlord, a principal in Terra Holdings, and Harry Macklowe’s son-in-law. Swig’s standing has suffered, though, as he’s lost control of development projects, faced an onslaught of litigation and separated from his wife. Many of Swig’s troubles centered around his conversion of the Sheffield57 on West 57th Street, which faced numerous lawsuits from tenants after he bought it with other investors for $418 million in 2005. Swig made headlines when one of those partners, Yair Levy, hit him in the head with an ice bucket during a 2008 meeting. The team lost control of the building to a creditor in 2009. The same year, Lehman Brothers filed to foreclose on 45 Broad Street, where Swig (and partners including Robert De Niro) intended to develop a hotel. In 2010, Swig closed the Helmsley-Spear brokerage, which he’d purchased a few years prior, and defaulted on a $12 million loan at 80 Broad Street. Swig, a California transplant and a surfer, also faces personal financial woes, with a reported $50 million in personal debt. In an exclusive interview with The Real Deal last December, however, Swig was sanguine about his future prospects, and said he’d made an agreement with the creditor that took over the Sheffield, Fortress, that gives him a share of potentially “enormous” future profits. He also said that as part of the agreement, he’d agreed to be depicted as “the fall guy” in the press.

While many developers have seen reversals of fortune in recent years, few have been as colorful and well-publicized as Kent Swig’s. Until a few years ago, Swig was considered real estate royalty: a prominent commercial landlord, a principal in Terra Holdings, and Harry Macklowe’s son-in-law. Swig’s standing has suffered, though, as he’s lost control of development projects, faced an onslaught of litigation and separated from his wife. Many of Swig’s troubles centered around his conversion of the Sheffield57 on West 57th Street, which faced numerous lawsuits from tenants after he bought it with other investors for $418 million in 2005. Swig made headlines when one of those partners, Yair Levy, hit him in the head with an ice bucket during a 2008 meeting. The team lost control of the building to a creditor in 2009. The same year, Lehman Brothers filed to foreclose on 45 Broad Street, where Swig (and partners including Robert De Niro) intended to develop a hotel. In 2010, Swig closed the Helmsley-Spear brokerage, which he’d purchased a few years prior, and defaulted on a $12 million loan at 80 Broad Street. Swig, a California transplant and a surfer, also faces personal financial woes, with a reported $50 million in personal debt. In an exclusive interview with The Real Deal last December, however, Swig was sanguine about his future prospects, and said he’d made an agreement with the creditor that took over the Sheffield, Fortress, that gives him a share of potentially “enormous” future profits. He also said that as part of the agreement, he’d agreed to be depicted as “the fall guy” in the press.

Predicting NYC’s future ghost towers

In early 2009, when the real estate market was in the darkest of places, The Real Deal surveyed the new development landscape to see which projects were most at risk for becoming empty “ghost towers.” At the time, the trend was already a serious problem in hard-hit cities like Miami and Las Vegas. Sources indicated that there were 23 residential projects in New York City that were in danger of sitting empty for the foreseeable future, while real estate data provider StreetEasy showed that around 45 percent of the more than 18,000 new units that had come to market in recent years had yet to sell. And, there was still more inventory waiting in the wings. A number of the troubled developments The Real Deal identified at the time wound up turning into rentals, including the 346-unit Financial District development 25 Broad, the 62-unit building at 111 Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, and the 130-unit project at 110 Green Street in Greenpoint. Others, like Rector Square in Battery Park City, saw their developers default or get crushed in foreclosures. However, Rector Square and many others were revived under new ownership. And things eventually turned up for the condos that turned rental, too. The rental market has been strong over the past year, with the vacancy rate reportedly dropping and Manhattan rental rates increasing to an average of $2,888 in the second quarter of this year, a 10 percent jump from the same time in 2010, according to Citi Habitats. Rental development has also been strong. At 2 Cooper Square, which opened last summer, two apartments rented for more than $20,000 a month, while rents started at $2,630 a month for studios at the 903-unit, Frank Gehry-designed 8 Spruce Street when it launched earlier this year.

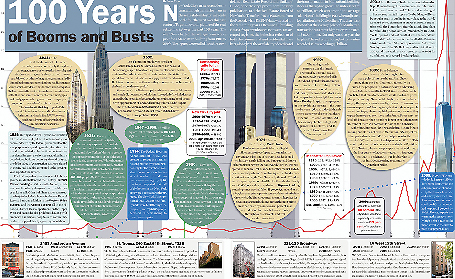

Charting a century of booms and busts

While there’s no question that the 2008 financial crisis led to a severe real estate downturn, an analysis conducted by The Real Deal last year found that Manhattan’s most recent bust probably only ranked as the fourth-worst in the past century, behind the Great Depression and the slump during the 1970s, as well as the savings-and-loan crisis during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The spread — by reporter Sarah Ryley and headlined “100 Years of Booms and Busts” — was awarded “best commercial real estate story by a trade magazine” by the National Association of Real Estate Editors for 2010. Indeed, residential prices are generally said to be down less than 20 percent from peak levels, which The Real Deal‘s analysis found was much less of a decline than in the other downturns — especially compared to the Depression, when values plummeted by a reported 74 percent. Job losses haven’t been as severe, either: The city lost about 65,800 jobs between January 2008 and April 2010. By contrast, it lost 551,900 jobs during the 1970s downturn. Office vacancy also hadn’t reached levels seen in previous busts, with Grubb & Ellis reporting that it stood at 10.2 percent as of mid-2010, well below the engorged amount of space available during the earlier downturns. Still, the busts share common characteristics — easy credit resulted in building booms in each case — and in some respects, the most recent contraction has proven itself to be second only to the Depression: The 67 percent drop in Manhattan in the average transaction price of all forms of real estate between 2007 and 2009 was topped only by the 72 percent drop during the Depression.

While there’s no question that the 2008 financial crisis led to a severe real estate downturn, an analysis conducted by The Real Deal last year found that Manhattan’s most recent bust probably only ranked as the fourth-worst in the past century, behind the Great Depression and the slump during the 1970s, as well as the savings-and-loan crisis during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The spread — by reporter Sarah Ryley and headlined “100 Years of Booms and Busts” — was awarded “best commercial real estate story by a trade magazine” by the National Association of Real Estate Editors for 2010. Indeed, residential prices are generally said to be down less than 20 percent from peak levels, which The Real Deal‘s analysis found was much less of a decline than in the other downturns — especially compared to the Depression, when values plummeted by a reported 74 percent. Job losses haven’t been as severe, either: The city lost about 65,800 jobs between January 2008 and April 2010. By contrast, it lost 551,900 jobs during the 1970s downturn. Office vacancy also hadn’t reached levels seen in previous busts, with Grubb & Ellis reporting that it stood at 10.2 percent as of mid-2010, well below the engorged amount of space available during the earlier downturns. Still, the busts share common characteristics — easy credit resulted in building booms in each case — and in some respects, the most recent contraction has proven itself to be second only to the Depression: The 67 percent drop in Manhattan in the average transaction price of all forms of real estate between 2007 and 2009 was topped only by the 72 percent drop during the Depression.

Sharif El-Gamal speaks out

Sharif El-Gamal, photographed for the magazine’s October 2010 issueLast fall, at the height of the controversy about Park51 — the planned 15-story, $100 million community center and Islamic prayer space a couple of blocks away from ground zero —The Real Deal ran an exclusive interview with the project’s lead developer, Sharif El-Gamal. Park51 had become a tabloid sensation, with the controversy fueled by opponents who referred to it as the “Ground Zero Mosque,” saying it didn’t belong so close to the World Trade Center. In the interview, El-Gamal, chairman and CEO of the real estate investment firm Soho Properties, stressed that it was neither a mosque nor located at ground zero, and that there “was a narrative that was built in to provoke and sensationalize a topic that should not have gotten the attention that it got.” El-Gamal also said that despite the project’s aims being distorted by critics, the amount of attention had also been a boon for his business, as the “amount of money that wants to come into a real estate deal for us right now is unbelievable.” More recently, El-Gamal has been quoted saying that the construction of Park51 won’t begin for at least five years.

Behind the scenes at the Google deal

111 Eighth Avenue, which Google purchased for $1.77 billion

In December 2010, Google closed on the purchase of 111 Eighth Avenue for $1.77 billion. The technology giant’s buy of the 2.9 million-square-foot building was the largest U.S. building purchase last year. In July, The Real Deal took a behind-the-scenes look at how the Google deal unfolded, including how the building’s owners agreed to stop actively marketing the property for two nail-biting weeks while the Internet giant’s top brass was deciding whether to approve the purchase. The deal was also seen as a sign of the current, tentative recovery. Data from Cushman & Wakefield indicates that the market dipped from its peak in 2007, when $48.5 billion of investment sales traded, to a low of $3.5 billion in 2009, before rebounding to $13.6 billion in 2010. Market reports so far this year indicate further recovery in the commercial market, which some attribute in part to historically low cap rates. A report from Eastern Consolidated pegged the second-quarter investment sales total at $9.4 billion. Office-property sales, while still lagging in terms of number of transactions, have been bolstered by big-ticket transactions such as Paramount Group’s purchase of a minority interest in 1633 Broadway for $980 million, and Monday Properties’ $760 million recapitalization of 230 Park Avenue through Invesco.

Sizing up Condé Nast’s WTC lease

A rendering of One World Trade Center Condé Nast Publications reached an agreement to become the anchor tenant of One World Trade Center this May — a deal that has been hailed as an overwhelmingly positive development for the future of the World Trade Center and a potential game-changer for the city’s commercial market. The media giant’s lease for 1 million square feet of space in the skyscraper reportedly works out to around $60 a foot. The agreement not only gives the World Trade Center skyscraper a solid corporate tenant, but also lends cachet to the complex, and positions it, and Lower Manhattan, as a potential home to firms outside of the government and financial sectors. After the lease was inked, The Real Deal reported that it was indicative of a larger trend of companies being willing to consider office space outside of Midtown. Downtown is still the weakest office market in New York, though there are signs of improvement beyond the Condé Nast deal: The availability rate was down to 13 percent in June, its lowest level since peaking at 15 percent in June 2010. This month, The Real Deal has a two-page spread looking at how the World Trade Center buildings price out for the developers who are building them.