Shelter Island was caught in a crosscurrent.

In 2019, a couple of years after local officials slapped limits on short-term rentals, some homeowners were still furious.

The law forbade any rentals under two weeks long and some of homeowners complained they could not make ends meet without having that regular rental income. Others sued the municipality in federal court, arguing their basic property rights were being denied, but a federal judge dismissed most of the suit’s claims last April.

In June 2019, officials relented and relaxed the rules. Now, owners who remain in their houses while renters spend the night can lease out their properties as often as they like. If owners are financially struggling and can prove hardship, they can also rent out investment properties where they don’t actually live, though only once a week in the summer. All rentals require a permit, good for two years.

“Our primary purpose was to discourage the professionalization of these kinds of rentals,” said Robert DeStefano Jr., Shelter Island’s attorney. “But you have to be flexible to deal with reality.”

Facing a surge of short-term rentals over the past few years, communities like Shelter Island are struggling to balance quality of life against property rights.

Perhaps the most galvanizing clash has been in Jersey City, which banned investor- and tenant-controlled rentals last summer and then fought off a multimillion-dollar lobbying effort by Airbnb to try to overturn the rule through a November referendum.

But outside of the spotlight — and in some cases several years before Jersey City’s efforts — cities, towns and villages across the tri-state region have made their own attempts to keep the home-sharing economy in check.

With Airbnb expected to go public this year, the company has more at stake with each municipal fight. The firm has had a valuation between $31 and $35 billion in recent years, but in the first three quarters of 2019, the company reported a loss of $322 million, reversing a $200 million profit over the same period in 2018.

With Airbnb expected to go public this year, the company has more at stake with each municipal fight. The firm has had a valuation between $31 and $35 billion in recent years, but in the first three quarters of 2019, the company reported a loss of $322 million, reversing a $200 million profit over the same period in 2018.

How tightly is Airbnb controlled? It’s a patchwork across the region. Beachy parts of Long Island that draw hordes of seasonal renters have pumped the brakes on home-share apps. But less popular areas, such as Babylon Village in Suffolk County, have also made it tougher to rent a home.

On the other hand, areas that are neither close to Manhattan nor have great resort appeal, such as suburban Westchester County, appear to have essentially tabled any bans.

Laws about who can rent houses and for how long are just one potential hindrance to the rental industry. Another is taxes. There have been more lodging-type taxes imposed on Airbnb and other short-term stay platforms in recent years, as the rival hotel industry, in a bid to level the playing field, has pushed municipalities to approve them.

In New York and elsewhere, Airbnb itself is offering to help collect sales and other taxes on its rentals, which under the current system are submitted voluntarily by the hosts. In Connecticut, the company does collect local taxes through its website before remitting them to state officials.

Below, The Real Deal looks at the strongest forces shaping the short-term home rental market, from the East End to the Constitution State.

New Jersey

New York’s clamp-down on rentals in recent years pushed the home-sharing industry, which includes services like FlipKey and HomeAway, across the Hudson River. Some areas of the Garden State detected early on the potential for problems.

In December 2015, Union City in Hudson County struck first, passing a ban on any rentals for 30 days or less, then tightening the law a few months later to prohibit rentals than 30 days even when a host is home.

“In order for us to continue to improve the quality of life, the city must preserve its available housing stock,” Union City Mayor and State Sen. Brian Stack said in a statement at the time.

In fall 2016, nearby Fort Lee, in Bergen County, followed suit with its own 30-day rule. Other Bergen towns following with similar laws in rapid succession, like Lyndhurst (2017), Paramus (2018) and Secaucus (2019). Violators can be punished with fines of thousands of dollars a day.

Under pressure from hoteliers, lawmakers in October 2018 expanded the statewide occupancy fee to cover houses that accommodate paying short-term guests. The fee, which can be as high as 5 percent, is layered on top of a required 6.625 percent sales tax.

However, those extra fees didn’t sit well with owners of Jersey Shore rental homes that rely on summer visitors. Acknowledging their concerns, officials this past December narrowed the law to exclude properties that market themselves directly, by way of lawn signs and the like, as opposed to using mass-market online platforms.

The Jersey City Battle Royale

In some ways, Jersey City has zigged while its neighbors have zagged. In 2015, while neighboring communities were giving a cold shoulder to Airbnb, the Hudson County city was giving it a warm embrace, though it did slap a 6 percent lodging tax on its users, resulting in $4 million in tax revenue between 2016 and early 2019. But within a few years, the city’s mayor, Steve Fulop, reversed his position after hearing complaints about how Airbnb’s were reducing the supply of long-term apartments, ballooning housing costs.

Across Jersey City, 72 percent of Airbnb listings are by hosts with multiple properties, according to Inside Airbnb, an independently run data service critical of the company. That suggests a huge number of commercial operators, as opposed to the mom-and-pop landlords that Airbnb often claims are its mainstays.

“The most important part was to keep rents affordable for newcomers, and for people just trying to make it,” said Council member James Solomon, a co-sponsor of the Jersey City bill enacted in June 2019, which essentially allows units to be rented only if they are in a building with four or fewer apartments and the owner is home.

For its part, Airbnb blamed Fulop’s flip-flop on hotel-industry campaign contributions, but Fulop denied the accusation.

“I think we have to pretty jealously guard our housing supply,” said Solomon, who added that the money generated through the 6 percent city hospitality tax on Airbnbs was a pittance considering the city’s $600 million budget. “The negatives outweigh the positives.”

Westchester County

Among the first municipalities to push back against home-sharing was New York City, through a measure passed by the state, which sets housing law. As a result, communities that are seeking to curb rentals seem to follow New York’s lead.

In 2010, two years after the founding of Airbnb, New York made it illegal to rent apartments for shorter than 30 days when the owner wasn’t there. But the law was frequently flouted, according to officials, who in 2016 added new muscle. Putting hosts on the hook as much landlords, the state created a system of hefty fines for anybody posting an online ad about an illegal apartment rental, or up to $7,500 for a third offense.

But the laws, which Airbnb challenged with a federal lawsuit, mostly focused on apartment buildings, leaving it up to towns to decide what to do about single-family houses.

The controversy doesn’t seem to have roiled wealthy Westchester, which has had a county-wide three percent occupancy tax on the books since the 1980s, and where most municipalities, as of 2017, also impose their own 3 percent tax, which Airbnb collects.

Overall, restrictions in the county seem almost nonexistent. In Mamaroneck, a waterfront town of about 30,000, for instance, there has been talk through the years about tweaking zoning, but nothing has come to fruition.

“I know it’s not an easy issue for communities to deal with,” Mamaroneck supervisor Nancy Seligson said. “But we just haven’t had many complaints.”

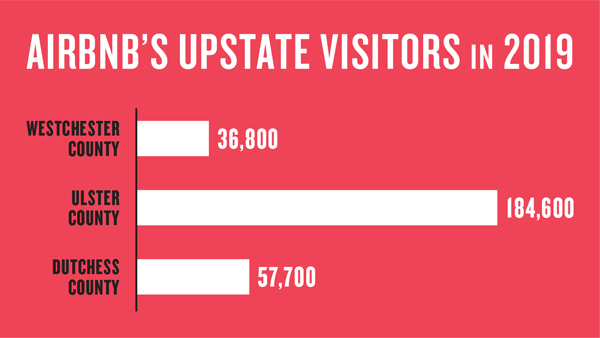

A relatively small market may have something to do with it. Last year, 36,800 Airbnb users visited Westchester and spent about $9 million, according to the company. By comparison, Ulster County, in the Catskills, had 184,600 visitors, followed by Dutchess County with 57,700.

Long Island

Shelter Island isn’t the only resort town cracking down on short-term stays. In East Hampton, zoning had already limited renters to stays of less than two week only twice every six months — conceivably just two summer weekends — since the 1980s. But the rash of online rentals earlier in the decade, which angered brokers by cutting them out of the deals, pushed the town in 2016 to adopt a rental registry to better enforce existing laws, officials said.

Southampton formed a rental registry in 2015, the same year that the North Fork town of Southold imposed a two-week minimum stay restriction.

Farther west in Suffolk County, in an area not usually known for rowdy group rentals, the village of Babylon last year passed Local Law 8, which prohibits owners from renting out their houses for less than a month at a time. Owners can be incarcerated for 15 days for violating it.

The hotel industry does not seem to have been a factor. “I was getting complaints about strange people who were not related to the homeowner,” said Ralph Scordino, the mayor of Babylon. “But it was also about being afraid of fires and car accidents.”

“Airbnb is a good way to ruin a community,” he added.

The landlocked villages of New Hyde Park (which has a 28-day minimum) and the Branch (which has a 30-day minimum), also passed bans in the last few years. Because the areas don’t have much in the way of vacation demand, the restrictions seem to be a strike against party houses, like in Babylon. Representatives for the villages did not return calls for comment.

In December, following a Halloween party shooting at an Airbnb rental in California, Airbnb unveiled a “Party House Ban” — a $150 million effort that could lead to suspended accounts if renters are too loud or if they smoke when it’s prohibited. A new dedicated phone line will allow officials to call with complaints.

Short-term rentals have become so common in some neighborhoods that blanket bans can be difficult, officials say.

Around 2015, on Saltaire, a 400-house village on Fire Island, officials began to notice ads on Airbnb for one-night rentals offering 12 rooms at a time, which raised safety concerns, said John Zaccaro, Saltaire’s mayor.

“We foresaw that if it continued, it would be a difficult thing as a municipality to handle, from a financial and health and safety perspective,” he said.

The proposed solution was to let landlords rent their homes for a minimum of two weeks a pop, four times a year, Zaccaro said. But owners protested, saying they had come to depend on the income. So the village tacked on a fifth rental period of a single week to let owners capture some of the short-term audience.

Zaccaro, a Manhattan-based real-estate developer, said he believes the Airbnb’s of the world should be regulated. “The concerns are legitimate,” he said.

Connecticut

Relative to other parts of the region, Connecticut can seem like the Wild West. Since 2016 the state has imposed a hefty lodging tax of 15 percent on hosts, money which Airbnb collects through its site. Yet very few of Connecticut’s 169 towns seem to rein in home-share services.

Most of the towns that regulate rentals tend to be inland, away from the touristy parts of the state. The city of Hartford in 2016 passed a strict law stipulating that owners can host guests for only 21 days every six months and need to be on site and to have a single-family house.

In some cases, existing ordinances may be protective enough. For instance, in Ridgefield, any short-term housing is considered a bed-and-breakfast, a use that requires a special permit. The town has forced hosts to shut down over a lack of permits, and few have sought one out, officials said.

And in New Fairfield, zoning laws were amended in January to require permits for any house seeking a rental six days or fewer. Owners also have to be present, or at least next door, according to the new rules, which take effect in March.

But Airbnb listings don’t seem to be a hot-button issue in Greenwich, Stamford, Norwalk, Bridgeport or Fairfield, which all have hosts offering short-term rentals even though some zoning boards forbid them.

But for Airbnb, it has not always been smooth sailing in Connecticut. Last year, a lawmaker unveiled a bill that would have created tough new statewide rules, including a 90-day cap on non-owner-occupied rentals, and allowed towns to ask owners to pay an additional tax of up to 6 percent. The bill, No. 7177, was defeated.