Discount retailers. Luxury department stores. Children’s stores. Home goods giants.

The retailers that have filed for bankruptcy so far in 2019 — and those on experts’ watch lists — have spanned the spectrum.

And with an ever-growing list of stores in the red, the outlook for the real estate they occupy continues to be grim. While some retailers, like young-adult fashion chain Forever 21, plan to use bankruptcy filings to right-size real estate portfolios, others, like Payless, have opted to close hundreds of stores.

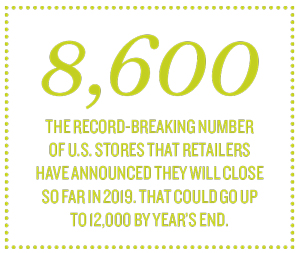

So far this year, U.S. retailers have announced plans to shutter almost 8,600 stores, a figure far surpassing the number from last year — which saw the bankruptcy of big-box retailer Sears. And store closures are on pace to hit nearly 12,000 by the end of the year, according to data firm Coresight Research, a retail consultant.

That 8,600 figure is already higher than the record-breaking 7,000 closures in 2017, which saw bankruptcy filings from household names like Toys “R” Us and RadioShack.

“There are a lot of stores that are too big out there, there are a lot of stores that become redundant,” said Gilbert Harrison, founder of retail financial advisory firm Harrison Group. “We’ve been overstored for a long time.”

For those in the industry, it’s a tired story. “I don’t think anyone’s devastated or surprised,” said Carl Mattone, president and CEO of Queens-based CFM Development. “It’s just the world that we live in.”

In the tri-state area, retail investment has been a mixed bag. Fairfield County, Long Island and New Jersey saw varying dollar-volume drops in the first half of 2019 compared to the same period in 2018, according to Avison Young. But Westchester saw increases.

Meanwhile, Moody’s Analytics REIS found that the retail vacancy rate for the region — which it counted as Northern New Jersey, Long Island and Fairfield and Westchester counties — hit 8.5 percent in 2019’s third quarter. That was up from 8 percent year-over-year and 5.9 percent in 2011, when the economy started recovering after the last recession.

Malls, including those throughout the tri-state, are obviously feeling the pinch, as TRD and others have long been reporting. Some experts predict that the number of U.S. malls, which now stands at roughly 1,200, could end up at just a few hundred once the dust settles.

Malls, including those throughout the tri-state, are obviously feeling the pinch, as TRD and others have long been reporting. Some experts predict that the number of U.S. malls, which now stands at roughly 1,200, could end up at just a few hundred once the dust settles.

That also means that major mall landlords will continue to take hits — even as sophisticated owners have taken proactive measures to buffer against major tenants collapsing.

Regional mall real estate investment trusts, for instance, posted annual losses of 13.5 percent, according to September data from Barclays.

Still, it’s not all bad news. While closures abound, retailers have so far said they would open about 3,600 stores this year, slightly more than last year’s 3,300.

In addition, tenants are taking advantage of the market.

“The tenant has a lot of control right now,” said Greg Tannor, executive managing director and principal at brokerage Lee & Associates.

As they do in tough markets, landlords are getting creative to fill space — whether it’s signing online-native brands or adding entertainment amenities to their properties.

The American Dream mall, which partially opened in October in New Jersey, will feature an indoor amusement park and ski slope, for instance. And Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield’s Garden State Plaza, also in New Jersey, is getting a makeover that will include housing.

In addition, there’s demand from medical tenants and new food and beverage concepts, experts said. “The key to real estate — even if you’ve heard this a million times — is location, location, location,” said Joseph French, a retail broker with Marcus & Millichap in Westchester. “It may not be retail, but it will be something.”

Here’s a look at some of the retailers struggling the most.

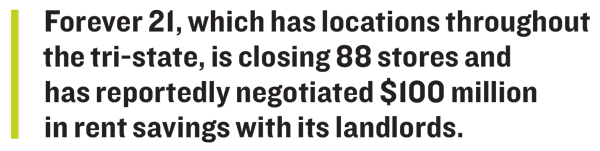

Forever 21 is closing 88 stores throughout the U.S.

Forever 21

Forever 21 may not be Forever after all.

The fast-fashion retailer filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in September.

The Los Angeles-based company, with 549 stores in the U.S. and another 251 overseas, said in its court filings that it did not have enough money to pay its vendors for the inventory it needs for the upcoming holiday season. It also blamed declining mall foot traffic and ballooning costs — the retailer was shelling out $450 million annually to stay in its stores.

The filing offered a glimpse into the family-run business, which had been controlled by husband-and-wife duo Do Won Chang and Jin Sook Chang since the company’s founding in 1984. Described in court records as the couple’s “American Dream,” at its peak Forever 21 was raking in more than $4 billion in sales annually.

But former employees and industry insiders told the New York Times that the Changs were reluctant to bring in outsiders to help with business decisions and that their micromanagement and overall keep-it-in-the-family ethos perpetuated the chain’s decline.

As part of its restructuring, the retailer initially announced that it would close 178 U.S. locations. But in November, it lowered that to 88 and negotiated $100 million in rent savings, the Wall Street Journal reported.

Bankruptcy court records from late October, however, still showed around 100 closures, including nine in New York state, two in Connecticut and two in New Jersey.

Stores that were on the chopping block at that point included sites in Short Hills, New Jersey; Danbury, Connecticut; and White Plains. It’s unclear which of them (or any others) will be spared.

Forever 21’s stores — generally considered “junior anchors” at between 20,000 and 40,000 square feet — may be challenging to deal with, said Marcus & Millichap’s French.

“It’s a big chunk of space that’s going to be hard to fill,” he said. “Honestly, these landlords, the malls today, are struggling for tenants … a box of that size, there aren’t a lot of players in that space.”

And some landlords will get hit harder than others. For example, Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, as of the October count, had 16 Forever 21 stores closing, including one at the Sunrise Mall in Massapequa on Long Island.

Meanwhile, Macerich, Taubman Centers, Simon Property Group, Brookfield Properties and Vornado Realty Trust rank among the company’s 50 largest unsecured creditors. Forever 21 collectively owes those five mall owners $20.9 million, bankruptcy records show.

Taubman — which counted Forever 21 as its biggest tenant, accounting for 4.3 percent of its malls’ gross leasable area — told investors that it anticipated the shift and proactively took back some Forever 21 spaces. CEO Robert Taubman said the company recaptured about 5 percent of Forever 21’s square footage, including two large stores in China that have been re-leased. “There’s a lot of uncertainty. … But we’ll have to see, and it is a very fluid situation,” he told investors during a second-quarter earnings call.

French said the “smarter mall operators have already seen this coming.”

“They’re not shocked by it,” he said. “They’ve been looking for tenants to backfill this space.”

Payless ShoeSource

Payless ShoeSource filed for Chapter 11 in February — and not for the first time.

The discount-shoe company filed for bankruptcy just two years before, and re-emerged having closed 675 stores and shedding $435 million in debt.

But that restructuring wasn’t enough. This year, the roughly 60-year-old company closed all of its 2,500 stores in the U.S., Puerto Rico and Canada, including about 30 in Connecticut, 80 in New Jersey and 150 in New York state.

Stores in Jersey City, Stamford, Port Washington and Westwood (which is in New Jersey’s Bergen County) were also among the shuttered tri-state area locations — plus 27 Brooklyn outposts. French said, however, that the company’s spaces won’t be as difficult to fill because they average only 3,000 square feet, according to A&G Realty Partners, which was hired to dispose of the locations. “It depends where they are … [but] they are a much more manageable size,” French said.

Still, Payless’ bankruptcy marks an epic downfall for the Kansas-based company, which was founded by cousins Louis and Shaol Pozez and at its peak had over 4,500 stores.

Payless — which during its first bankruptcy was taken over by a group of lenders, including Alden Global Capital — cited production issues and inventory oversupply among the chief reasons it needed bankruptcy protection.While its North American locations have been liquidated, the company has no plans to shut down its 790 international stores.

One source said the company’s heavy debt load — which clocks in at $450 million — is a result of its private equity buyout. That, he said, has led to its insurmountable financial woes.

“Payless Shoes didn’t fail because of e-commerce. Payless Shoes failed because of [private equity],” French said. “Private equity has killed more retailers than e-commerce.”

Barneys New York

Barneys is known for carrying designer brands — think $450 J Brand jeans, $1,500 Victoria Beckham boots and $3,000 Prada purses — that are unaffordable to the masses. But the department store chain could not afford its own rent.

And it has made no bones about that, attributing its August bankruptcy to rent hikes.

Ashkenazy Acquisition — the landlord at the store’s 275,000-square-foot flagship on Madison Avenue in Manhattan — slapped Barneys with the biggest increase.

Last January, the landlord, which bought the iconic building during Barneys’ first bankruptcy in the 1990s, increased the rent to $30 million from $16 million. The jump stemmed from a provision in Barneys’ lease that allowed Ben Ashkenazy’s firm to bump rates up to fair market value.

Barneys is liquidating all of its stores in the wake of its bankruptcy filing

Lee’s Tannor said department stores are getting hit particularly hard by online competition because it’s more convenient to click and buy than to walk into a behemoth of a store. They also have slimmer margins because they’re selling a collection of brands from third parties. As a result, he said, they can’t handle escalating rents.

Barneys’ filing indicates that rents are out of line with “where the reality is,” Tannor said.

And Barneys’ bankruptcy made clear that it’s not just the mid-tier players hurting. “The luxury end of the market is suffering in general,” said Stephen Selbst, chair of the restructuring and bankruptcy group at the law firm Herrick Feinstein.

Neiman Marcus also has been hindered by a large debt load, and two years ago Ralph Lauren shuttered its flagship on Fifth Avenue.

Barneys originally planned to shut 15 of its 22 outposts, including its Riverhead outlet store on Long Island and six locations in California. But after Authentic Brands Group — which owns designers like Frye and Vince Camuto — and B. Riley Financial received court approval to take over Barneys for about $270 million, the firms moved to liquidate all the stores, including those at Woodbury Common Premium Outlets in Central Valley, New York.

Ashkenazy has said the Madison Avenue flagship will stay open for at least a year, and ABG said it will become a pop-up store, though details on how that would work and the timeline remain unclear. Meanwhile, ABG also will license Barneys’ name to Saks Fifth Avenue.

The retailer counts some of its landlords among its biggest (unsecured) creditors.

For example, it owes Jenel Management Corporation, which co-owns 660 Madison with Ashkenazy and owns a Barneys Beverly Hills outpost, $5.98 million. It also owes Thor Equities, which owns its Chicago site, $2.23 million. That’s not to mention the fashion brands from Gucci to Prada that also have piles of unpaid bills.

Barneys also filed for Chapter 11 in 1996, partly because of a dispute with a Japanese department store chain it had partnered with, according to court records. The company re-emerged two years later.

Do Won Chang and Robert Taubman

Gymboree

The competition in the kids’ clothing world got the best of Gymboree this year.

The children’s store filed for bankruptcy in January and announced that it would close all of its nearly 800 Gymboree and discount Crazy 8 stores in North America.

Gap, however, bought Gymboree’s high-end children’s clothing line, Janie and Jack, and plans to keep over 100 locations open. And in October, the Children’s Place announced that it will reopen 200 Gymboree stores in select locations and online.

Gymboree was mostly located in malls. And the retailer’s bankruptcy filing provides details about some of the landlords and locations impacted.

The company, for example, owes Simon and Brookfield a combined $3.6 million in rent. Simon’s stores in the tri-state area include a Janie and Jack at Roosevelt Field Mall in Garden City, and Brookfield has a Gymboree at Bridgewater Commons in New Jersey. And among Taubman’s stores is a Gymboree at the Short Hills Mall, bankruptcy records show.

In general, unsecured claims, which most landlords file, are not prioritized in bankruptcy court, said Herrick’s Selbst. In the Sears case, “No unsecured creditor is going to get anything,” he said.

And in its initial bankruptcy filings, Gymboree provided no “cure” amounts to its landlords for breaking the leases.

One source, who works for a national landlord and asked to remain anonymous, said that owners get regular financial updates from tenants and take back space if they sense closures coming.

“Our leasing team has been very proactive to get in front of these bankruptcies,” the source said, noting that the landlord began taking back spaces from Sears in 2010, long before that company went bankrupt.

A landlord with a master lease for one tenant in multiple stores often has the upper hand, said bankruptcy attorney Brett Miller, managing partner of Morrison Foerster’s New York office. “That becomes harder for the company to just say, ‘Well, I don’t want these three but I want the other 10.’”

As with Barneys and Payless, the Gymboree filing was the second for the company — its first was in 2017. At that time, it cut $900 million in debt and closed about 330 stores. But that gutting didn’t do the trick.

Charlotte Russe

Discount women’s apparel store Charlotte Russe filed for Chapter 11 in February and then kicked off liquidation sales at its 500-plus U.S. stores.

In the tri-state area, outposts at Danbury Fair, Stamford Town Center, Westfield Trumbull and Galleria White Plains closed. That was in addition to stores across New Jersey, including in Wayne, Paramus and Livingston. In New York City, one store on 34th Street in Manhattan has already shuttered.

But in April, after the closings commenced, Charlotte Russe tweeted that it, too, was staging a comeback, with plans to launch a new online presence and open 100 stores. It has since announced openings in places like Jersey City’s Newport Centre and the Brass Mill Center in Waterbury, Connecticut.

Still, the filing marks a reversal from just six years ago, when growing sales had the retailer considering an initial public offering. Mounting debt from a private equity takeover in 2009 — it was bought by Advent International — and declining sales shelved those IPO prospects.

Last year, the California-based company secured concessions from landlords and trimmed expenses. But sales continued to plummet, and in its bankruptcy filing Charlotte Russe acknowledged that it failed to balance its e-commerce needs with its in-store expenses — a common land mine for retailers these days.

Bed Bath & Beyond

Also on the chopping block is Bed Bath & Beyond, which last month announced it would close 60 stores nationwide — a figure that’s risen from initial estimates.

The company, which has not filed for bankruptcy, hasn’t identified which stores it’s shuttering, but it has 58 outposts in New York state — including six in Manhattan and two in Brooklyn — plus 36 in New Jersey and 17 in Connecticut. There’s also a location in New Hyde Park on Long Island.

The New Jersey-based company, which has 1,534 stores (including offshoot concepts) in North America, has installed a new board and CEO and has plans to upgrade about 160 of its highest-volume stores. Meanwhile, it said, it will continue to negotiate leases with all of its landlords and is exploring sale-leaseback deals across about 4 million square feet of space it owns.

Pier 1 Imports

The home goods retailer also has yet to file for bankruptcy, but it appears to be on industry watch lists — this year, S&P Global Ratings said the company was on the brink of collapsing.

And Pier 1’s planned closures have gone from bad to worse.

In April, the Texas-based company said it would close 45 of its roughly 1,000 stores in North America. But it later revised that, saying it may shutter up to 15 percent of its entire portfolio.

The company has yet to release a store closure list, but its website notes that it still has five outposts in New Jersey, including two in Paramus and one in Jersey City. There are five others scattered throughout New York City.

Meanwhile, Pier 1 has signed on with A&G Realty to optimize its store footprint and renegotiate its rents. The retailer expects to close more stores as it continues those negotiations, interim CEO Cheryl Bachelder said in a September earnings call.

“We have been holding active discussions with our landlords and are continuing to make progress in realizing occupancy cost reductions,” she said. “We are encouraging those landlords who have not yet participated in discussions to work with us.”