The drama over the Coconut Grove Playhouse project hasn’t reached its final act.

The controversial plan to demolish part of the property — but preserve the historic theater — was in the clear this summer when a major legal pushback led by Miami Mayor Francis Suarez ended.

But a new lawsuit has rekindled opposition to the project, which has been in the works for seven years. Fourteen Coconut Grove residents sued the county in late August alleging its plan to use $23.6 million in voter-approved bond financing for the project is illegal. The money, they say, will be used differently from that allowed in a 2004 referendum, which would be an alleged violation of state law.

Miami-Dade County wants to restore the three-story historic front building but substitute the 1,100-seat auditorium with a 300-seat one. The plan has pitted the county and supporters — who argue a smaller, modern auditorium is more financially feasible and allows for affinity between performers and the audience — against Coconut Grove residents and preservationists who want the entire theater kept and restored, including the auditorium.

The bond is meant to “reconstruct” the playhouse, as well as “restore its structural integrity and add to its performance and educational capabilities,” the suit says. Instead, the county will tear down roughly 80 percent of the building and replace it with a smaller auditorium, as well as retail and office space, according to the Miami-Dade Circuit Court complaint.

“We are having trouble wrapping our minds around how demolishing 83 percent of a building is restoring and enhancing it,” said Anthony Parrish, one of the plaintiffs.

The county’s plan resembles the saga of the Sears, Roebuck and Co. department store in downtown Miami, said attorney David Winker, who represents the plaintiffs. Although the Art Deco building was designated as historic in 1997, by 2001 only a seven-story tower was preserved.

Cities and counties have fallen into the habit of saying only a portion of a building is historically significant, allowing them to tear down the rest, he said. “The problem is cultural institutions don’t make money,” Winker said. “Theaters don’t make money.”

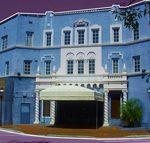

Developed in 1927 at 3500 Main Highway, the sky blue-colored playhouse was designed by the Kiehnel and Elliott firm, largely credited for introducing the Mediterranean architectural style to Miami. Robert Browning Parker renovated and redesigned the property in 1955, with a modern twist. It closed in 2006 amid financial trouble.

Under the county’s plan, GableStage, a local company, will operate the theater and handle programming once it reopens.

The project calls for keeping historical elements of the new theater such as the original double arch, with renderings showing lush landscaping, public plazas, paseos and a park allowing for outdoor movie screenings, programs and pop-up restaurants. The county also decreased the height of a planned 300-car garage by two stories, from 81 feet to 45 feet, according to a community presentation held late last year.

The claim that Miami-Dade is demolishing the playhouse is false, as the county is restoring the historic building and only tearing down “an addition” to the original structure, commissioner Raquel Regalado, whose district includes Coconut Grove, said in response to the suit.

Although Regalado was concerned the original project didn’t have a robust academic plan — which also was called for in the 2006 referendum — this has been remedied, she said. The county will not only add more educational space, but GablesStage expanded its offerings to include elementary and middle schools in programs already available to high schools, said Regalado, a former member of the Miami-Dade County Public Schools board.

“The historic part of the building, the original playhouse, we need to restore as soon as possible,” she said. “There are entire generations of Miamians who have not been able to enjoy this playhouse because of these [lawsuits].”

A previous skirmish started in 2019 when the county sued Miami, seeking to overturn Suarez’s veto of the city commission’s approval of Miami-Dade’s plan. (Although Miami-Dade, as well as Florida International University, lease the property from the state, Miami commissioners had a say in the project because the playhouse is within city limits.)

Read more

Last year, the county won after a court struck Suarez’s veto. He conceded defeat this summer by not pursuing more legal action that was due in June under a court-imposed deadline.

The National Register of Historic Places listed the playhouse in 2018. The Miami Historic and Environmental Preservation Board listed it in 2005. At the time, a preservation officer’s report deemed the façades as architecturally significant, but added that the entire building is historic.

“We are hoping that David [Winker] is going to find the right pebble in his little arsenal to throw at this giant called the county,” said Parrish, who was chairman of the city historic board in 2005. “Maybe the Goliath is finally going to topple.”