When Chinese, Iranian and Turkish investors received marketing brochures for the town of Palm Beach’s first EB-5 project in 2012, it seemed like a sure thing.

Pamphlets in Chinese and Farsi showed photos of the Clintons and Donald Trump as part of the Palm House condominium and hotel advisory board of “political and business leaders with worldwide experience.” In addition, the marketing materials named Celine Dion, Tony Bennett and billionaire Bill Koch as celebrity members at the hotel’s club.

But more than six years later, the Palm House’s planned $91 million makeover remains unfinished. The dilapidated 80,000-plus-square-foot hotel finally sold in a bankruptcy auction last month to a U.S. affiliate of the real estate investment firm London & Regional Properties for just shy of $40 million.

To add salt to the wound, Trump and Clinton were never on the project’s advisory board and almost none of the investors’ money went into the project.

Its developer, Robert Matthews — who lost the Palm House in a 2009 foreclosure before buying it a second time — instead used a chunk of the more than $45 million in EB-5 funding for personal expenses, including the purchase of a 151-foot yacht named “Alibi” and his own debt payments.

Matthews and the project’s general contractor, Nicholas Laudano, recently pleaded guilty to fraud charges in federal court, while the 91 EB-5 backers lost their $500,000 investments and never received their green cards.

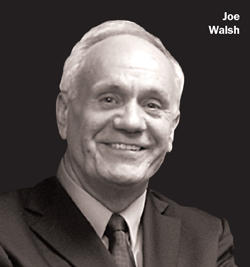

The EB-5 regional center in charge of marketing the Palm House project and soliciting the investments, however, has not been criminally charged. The South Atlantic Regional Center (SARC) and its director, Joseph Walsh Sr., were allegedly able to siphon nearly $9.5 million of the foreign investors’ money, according to a civil complaint filed by the SEC in federal court.

To date, Walsh has only been charged civilly. He was allegedly even found recently trying to solicit other EB-5 investors for another hotel project in Miami Beach, per a lawsuit filed in Palm Beach County.

“This is the most egregious fraud case I have ever seen,” said attorney David George, of George Gesten McDonald PLLC, who’s representing EB-5 investors in the Palm House lawsuit.

Regional centers like SARC function as middlemen between developers and their foreign investors. But despite the key role they play in the EB-5 process, there’s minimal regulation over how they operate and few safeguards to protect investors.

Regional centers like SARC function as middlemen between developers and their foreign investors. But despite the key role they play in the EB-5 process, there’s minimal regulation over how they operate and few safeguards to protect investors.

The current system, critics say, is a petri dish for fraud that allows bad actors to come and go — in many cases with no criminal prosecutions. At the same time, lobbyists for the real estate industry have pushed to ensure these rules remain in place.

“No one is watching the regional centers,” said Doug Litowitz, a Chicago attorney who was not involved in the Palm House lawsuit but represents Chinese clients in other EB-5 fraud cases. “There’s no clear punishment system … We just have to sue them for fraud.”

Connecticut’s “Gatsby”

Matthews, 61, gave investors the impression that he was a well-known luxury hotel developer with a global track record, including completed projects in New York, Bora Bora and Mexico. There is no evidence of him completing these projects.

Instead, his past dealings were mired in controversy and litigation, including another failed condo-hotel project in Nantucket called the Point Breeze that was forced into bankruptcy in 2010.

Matthews, who was raised in Massachusetts, moved to Connecticut in the mid-80s after dropping out of college and started buying up apartments and commercial properties in Waterbury. Locals there began drawing comparisons between Matthews and the fictional Jay Gatsby due to his ritzy parties and expensive tastes, according to the Hartford Courant.

He owned a 108-foot yacht named the Bon Vivant and claimed to possess North Carolina’s original Bill of Rights, which had been stolen by a Union soldier in 1865 and was recovered by the FBI just over 10 years ago. Adding to the Gatsby comparisons, Matthews became close with Connecticut’s then-governor, John Rowland, in the 90s.

The developer used his political connections to secure favorable contracts with the state government, allowing him to purchase government-owned property, among other things, according to the New York Times. To return the favor, Matthews allegedly bought a condo in Washington, D.C., from Rowland through a straw buyer in 1997 for nearly 20 percent more than what the governor had originally paid.

The condo sale and other business dealings eventually led to a corruption investigation into Rowland. But Matthews was never charged. So, he headed to South Florida where he first bought the historic Palm House — which needed substantial repairs — in 2006. Then six years later, Matthews began soliciting EB-5 investors for what he called Palm Beach’s last opportunity to build a “five-star hotel.”

The controversial federal program, which Congress first passed in 1990 and has repeatedly renewed since, gives foreign investors a path to U.S. citizenship if they invest $500,000 or more in a business venture that creates at least 10 new jobs. EB-5 investors generally function as individual lenders on those projects, but they rarely have a way to collect money if the project fails.

“The whole thing has to do with corralling desperate people in China, who believe that Americans wouldn’t lie to them out right,” Litowitz said.

And while the program was designed to create jobs in rural and distressed regions known as “targeted employment areas,” communities like Palm Beach — a top destination for wealthy retirees with a median household income of more than $110,000 — somehow met the same criteria.

Florida’s Department of Economic Opportunity approved the Palm House project for such a designation in 2012 because Palm Beach had an unemployment rate of 18.5 percent, above “the qualifying rate of 13.4 percent for that time period,” according to the state agency. Other EB-5 projects, including Hudson Yards in New York, the largest private real estate development in the country, were also able to take advantage of similar demographics.

Without mentioning his past dealings in Connecticut or in Nantucket, Matthews touted his wife Mia Matthews’ success as an actress, singer and star of the Nickelodeon show “Every Witch Way” and CW’s “South Beach,” which lasted all of one season. To further show off his connections and status in Palm Beach, he would take EB-5 immigration agents from China to a Mar-a-Lago charity event to meet Trump and take picture with him, according to a complaint filed by EB-5 investors in Palm Beach County Court.

The developer’s investment pitch also failed to mention that it was actually his second time acquiring the Palm House. And there was no mention of the fact that when he repurchased the hotel in 2013, along with the interest of its former owner, Glenn Straub, there was an unrecorded $27 million mortgage attached to the hotel.

Straub’s lawyer did not return a request for comment.

By the books?

To legally get EB-5 investors to put money into his project, Matthews was required to go through a regional center regulated by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services under the Department of Homeland Security.

So, he tapped Walsh — a South Florida resident who had a specious track record with development projects — to raise the money through SARC. While it’s unclear how the two met, Walsh allegedly lent Matthews more than $5 million of the foreign investors’ funds to keep his Palm Beach mansion from being foreclosed on.

In March 2014, Matthews sent Walsh an email to thank him for “saving [his] house,” according to the SEC complaint.

As more developers turned to EB-5 for cheap financing after the financial crisis, more regional centers received approval from the USCIS. From late 2014 to June 2019, the number of regional centers in the U.S. jumped nearly 60 percent to 884, according to USCIS. At the same time, close to 300 regional centers have been shuttered since 2007.

That high failure rate among EB-5 regional centers stems from an approval process that requires little effort, said Marcelo Diaz-Cortes, of the Miami-based law firm Levine Kellogg Lehman Schneider and Grossman. Diaz-Cortes, who has worked on EB-5 cases in Vermont, Palm Beach and Fort Lauderdale, added that a regional center “really just needs a business plan and numbers to support the government’s jobs projections and give the appearance that it is able to execute on that plan.”

But a handful of legal experts argued that there’s minimal oversight by USCIS during the course of most projects being built.

The agency is “inept at controlling the fraud,” said Michael Gibson, managing director at the EB-5 advisory firm USAdvisors.org. “No one knows who the true owners of the regional centers [are,] and there is no information on any of this. How can you deter fraud when there is no way for anyone to do any due diligence?”

A spokesperson for USCIS said the agency has a team of auditors that conduct compliance reviews on regional centers and noted in an email to The Real Deal that it “does not release information on specific EB-5 applications, investors or related projects due to [the Privacy Act] and other restrictions.”

“USCIS takes any violation of the law seriously, and we will explore all actions available to us to ensure the integrity of our immigration system,” the spokesperson added. “Where instances of fraud are suspected or proven within the program, USCIS takes appropriate measures to deal with any actors involved in the fraud, including terminating regional center designation.”

Regional centers have come under scrutiny for their roles in these EB-5 frauds in recent years.

USCIS shutdown Vermont’s sole EB-5 regional center last year on the heels of the country’s largest EB-5 fraud to date in the state’s so-called Northeast Kingdom.

Elsewhere, in Jupiter, Florida, Nicholas Mastroianni — who’s helped raise EB-5 funds for the Kushner family’s real estate projects — was sued last October over his Harbourside Place development by nearly 80 Chinese investors who accused him of defrauding them. Mastroianni has denied these charges.

One of the underlying problems is that regional center operators do not have to be general partners in EB-5 projects, said Jose Latour, an immigration attorney and founder of the Miami-based EB-5 regional center American Venture Solutions. In turn, regional centers do not have an obligation to protect investors’ money if a development project sours.

One of the underlying problems is that regional center operators do not have to be general partners in EB-5 projects, said Jose Latour, an immigration attorney and founder of the Miami-based EB-5 regional center American Venture Solutions. In turn, regional centers do not have an obligation to protect investors’ money if a development project sours.

“That’s where the weak link of the chain is — there is no real enforcement of the fiduciary rule to protect investors,” Latour added. “The regional center says, ‘Hey I’m not responsible.’”

The USCIS spokesperson said the agency has terminated nearly 220 regional centers since January 2017, due to evidence of foul play.

But U.S. legislators have continued to kick the EB-5 program down the road, giving it about 20 short-term extensions with many lasting only six months. And industry lobbyists have aggressively pushed back against any reform. The EB-5 trade group Invest in the USA has spent nearly $1.8 million lobbying on the federal program’s behalf since 2014, while the lobbying group for the Related Companies’ EB-5 business spent more than $500,000 in 2018 alone, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

“This is not unlike any other industry that can produce a toxic product like the opioid industry or the tobacco industry,” Gibson said. “There is a powerful interest involved. They don’t want any oversight. They don’t want information about their projects to come public.”

Blurry middlemen

Unlike Matthews, whose background is well documented in local news, SARC’s Walsh remains something of a mystery.

In the Palm House EB-5 marketing brochures, the smiling gray-haired regional center operator claims to have a background in advertising and electrical engineering. He also claims to have launched “several startup computer and graphics firms that he brought to the public markets in the late 1990s and early 2000s.”

Walsh could not be reached for comment through his lawyer.

His right-hand man at the now shuttered regional center was his son, Joseph Walsh Jr., whose other business ventures included running a blockchain “asteroid mining” company. The startup professes it discovered a $700 quintillion opportunity by selling the mineral rights to 600,000 asteroids in space, an investor prospectus claimed.

Walsh’s son did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Despite proclaiming innocence, Walsh is not in the U.S. to face any charges, according to multiple sources. George, the plaintiff attorney, said SARC’s founder is now either in Vietnam or Australia.

Walsh’s success in getting foreign backers on board for the planned Palm House project, according to the SEC’s complaint, was largely based on lies made to unsuspecting investors who believed the project carried minimal risk.

In bold font, one marketing brochure claimed that the EB-5 investor money would only be used for 43 percent of the project’s total costs while the rest would be covered by a $29 million loan from a “reputable bank” and $22 million in equity from the developer.

None of that was true.

SARC also claimed the investors’ funds would be held in an escrow account at PNC Bank until their green cards had been approved by USCIS and that the money wouldn’t be touched until then. Investors were even sent photos of a PNC account under the name “Palm House Hotel, LLLP Escrow Account.”

“They had no escrow account,” said George, who added that EB-5 legislation does not require developers to keep money in escrow. “It was a checking account.”

Fast withdrawals

As soon as deposits for the Palm House came in, Matthews, Walsh and Laudano, the project’s general contractor, allegedly began to withdraw money for personal uses.

After Matthews was charged with using the account as a piggy bank, Walsh fired off a press release last year claiming he and SARC had been absolved.

“It saddens me to see the waste of time, money and talent, and the human and financial capital that these conspirators perpetrated in multiple courts and plain good old fashion lies to continue their charade for years,” Walsh said in the release.

He even reportedly went a step further by hiring Brian Aryai, a certified accountant who claims to have worked as senior special agent for the Department of Homeland Security, to provide a detailed audit showing how the money was lost.

The report, meant to clear Walsh’s name, noted that he moved $9.3 million from the Palm House account to his own company through more than 39 individual transactions between September 2013 and January 2015.

SARC’s founder is now facing additional civil charges over an office condo project in Royal Palm Beach — another development SARC raised $6.5 million in EB-5 funds for.

“Walsh solicited and obtained investors for all of these projects,” George said.

But USCIS didn’t have to travel far to determine the unfinished project was a racket — the agency’s local office sits directly across the street from the Royal Palm site, according to Google Maps.

“It’s remarkable… These cases come and go, and there is no reform,” said Gibson, who cited “egregious misuse of funds [while] the industry continues without a bump in the road.”