UPDATED June 25, 2019: When Sam Zell’s Equity LifeStyle Properties snatched up a Davie mobile home park for $50.35 million in July of last year, the billionaire real estate mogul’s firm bought it for a staggering 97 times what the owners of the 100-acre property paid nearly half a century ago. Six months later, Equity LifeStyle picked up another mobile home park on 50 acres near Riviera Beach for $49.5 million, paying Palm Lakes Cooperative, a consortium of 468 mobile home lot owners, roughly $53,101 per lot.

The two purchases added 1,534 mobile home lots to Zell’s REIT, which currently owns 154,742 lots in 33 states and British Columbia, making Equity LifeStyle the largest mobile home park owner in North America. The firm is also Zell’s most profitable venture. For the quarter ended March 31, Equity Lifestyle posted a net income of $113.3 million, a $53.1 million increase compared to the same period in 2018.

According to Equity LifeStyle’s quarterly report filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the mobile home park business is in exponential growth mode. “We believe that demand from baby boomers for manufactured housing and RV communities will continue to outpace supply for several years,” the report states. “We also believe that our properties and our business model provide an opportunity for increased cash flows and appreciation in value.”

RELATED STORIES

— Doublewide: Bedrock acquires two mobile home parks in Riviera Beach

— The mobile home park model is “financially catastrophic” for homeowners, John Oliver says

— Sam Zell looking to go public with four Equity firms overseas

In South Florida, the Chicago magnate is competing against other institutional REITs, such as the Carlyle Group, that share Zell’s appetite for the mobile home parks’ profit margins. They’re also competing against local developers, such as the Treo Group, that are redeveloping trailer communities into residential projects.

“It is all about chasing yield and buying recession-proof product,” said Miami Beach-based commercial Realtor and Analytics Miami founder Ana Bozovic. “Equity groups and institutional investors all know we are at the end of the cycle, and mobile homes are the most recession-proof housing stock in existence.”

Bozovic said all of her big clients are sitting on cash and searching for assets that yield consistent returns. “The smart-money players like Zell have all made fortunes anticipating the next downturn, and this is what they are doing here,” she said. “Mobile homes are just cash machines. Institutional buyers can get a park at a 4 percent cap rate. Rents go up and they optimize the operation.”

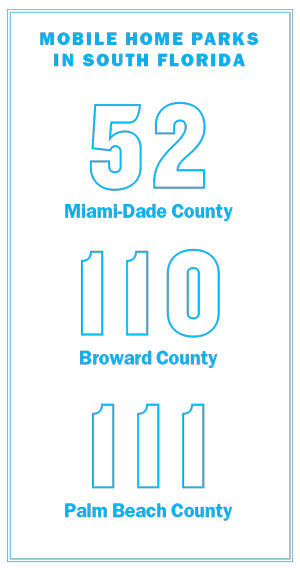

Dan Mulkey, vice president of investments for the Tampa office of Marcus & Millichap, said the low cap rates make mobile home parks one of the hottest asset classes in Florida. According to the Florida Department of Health, the agency that issues mobile home, lodging and recreational park licenses, there are 5,456 such facilities in the state. A majority are in Central and North Florida, while the tri-county region and the Keys have less than 400 parks combined. Miami-Dade has 52, Broward has 110, and Palm Beach has 111.

“They are very desirable, cash-flow-wise,” Mulkey said. “You don’t have to put up with a lot of dips in the economy, especially with the senior mobile home communities. Most of them pay rent with their Social Security checks. Even in a recession, they still pay rent.”

Mulkey, who specializes in mobile home park transactions, said he owns two small parks in Winter Haven and Zephyrhills. “I get calls all the time from people looking to buy mine, but they are not for sale,” he said. “I don’t blame them for trying.”

Investors believe Florida’s growing population and the high prices for residential real estate are going to create more demand for mobile homes, Mulkey said. “People are looking for places to live that they can afford to buy,” he explains. “Mobile parks fill in the gaps.”

Jaime Sturgis, a Fort Lauderdale commercial broker with Native Realty who is currently representing a couple of clients looking to buy a park, said that despite the uptick in transactions in 2018, it’s difficult to get a deal done. “Mobile home parks are few and far between, and generally not for sale,” Sturgis said. “Some that I have approached have flat out said no, and others want astronomical numbers that are out of touch with the market.”

He said some park owners have price expectations that are two to three times what the market would bear. For instance, some owners have thrown out figures in the $12 million-and-above range when price points between $5 million and $6 million are more in line with current trends, Sturgis explained.

“Buying a mobile home park is a long play. It can take up to 12 months to identify, negotiate and close on a property that meets the investors’ site criteria,” Sturgis said. “And the probability of success is low because you are looking for a finite product in a competitive marketplace.”

The captive customer

A big reason institutional investors are scouring for mobile home park deals has to do with the captive customer base, brokers said. People who actually live in the mobile homes are pretty much stuck and will have a hard time finding better housing alternatives. And at a time when the wealth gap in America is growing wider, institutional investors and developers are banking on a significant increase in the mobile home customer base. In the U.S., roughly 22 million people live in mobile homes, according to a 2018 report by the Manufactured Housing Institute, a trade association for the industry.

An early April episode of HBO’s “Last Week Tonight With John Oliver” aired a segment on the nuts and bolts of the mobile home real estate sector. Oliver explained that mobile homes’ owners have to rent the land underneath them and that their manufactured houses depreciate in value, creating a “financially catastrophic” situation. When a mobile home park owner sells the land to a major developer or private equity firm, the buyer will typically raise rents, pushing people out of their properties. Because it can cost tens of thousands of dollars to move the homes, jacking up the rents can lead people to walk away from their mobile homes, Oliver said.

Boosters like Mulkey downplay the darker side of the industry, noting that a majority of Florida’s mobile home parks are still mom-and-pop operations that form bonds with the residents. He also noted that Florida law has some protections in place for mobile home park owners.

“You can raise the rents only once a year, and it has to be a fair market increase,” Mulkey said. “You can’t gouge them.”

According to Sturgis, one of the obstacles he is facing from mom-and-pop operators is their relationships with the homeowners. “There is an emotional connection with the residents,” Sturgis said. “Should they sell, they fear the residents would have nowhere to go if they were to be displaced. There are no suitable alternatives for them to relocate to.”

Indeed, a couple of recent deals in Miami-Dade highlight this conundrum. In mid-March, residents of Pine Isle Mobile Home Community, a 55-and-older mobile home park in Homestead, received notices from the new owner, Treo Group, that they have until Oct. 31 to move out. More than two dozen households, which pay $400 a month to rent the pads their homes sit on, will be forced to leave. Treo bought the park with 317 lots in November of last year for $12.9 million and intends to redevelop the property according to a land use amendment application the company’s affiliate Mac Thirteen LLC submitted to Miami-Dade County. Treo wants to change the property’s designation so it can build up to 863 residential units instead of the maximum of 265 currently allowed. The application does not specify if the proposed units are rentals or for sale.

Unlike the mobile home park cash cows institutional investors covet, Pine Isle was an underperforming asset, according to an economic study Treo included in its application. As of February, 32 lots were occupied by year-round residents and another 28 were leased by seasonal residents, putting the park’s occupancy rate at 30 percent, according to the study. An apartment complex with more than 800 units could provide much higher returns.

An attorney representing the remaining homeowners recently told WLRN that they are attempting to negotiate with Treo to provide more money and more time for relocation. According to documents the firm submitted to the county, Treo executives have been helping the Pine Isles residents resettle in other Miami-Dade parks that have vacant mobile homes, since relocating their own trailers can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

If no agreement is reached, Florida provides mobile homeowners with $1,375 to find a new home, or $3,000 if the mobile home can be relocated. Both amounts are a drop in the bucket, said Evian White De Leon, deputy director of Miami Homes for All, an affordable housing advocacy group.

The $1,375 “doesn’t even get you into an apartment, let alone the last month and security deposits,” she said. “Shutting down these mobile home parks is digging the affordable housing holes deeper rather than alleviating it.”

A similar scenario played out in Hialeah shortly after two Delaware shell companies purchased the Sunny Gardens Mobile Home Park for $12 million in February 2018. Two months later, residents — a majority of whom are more than 70 years old and had lived in the Sunny Gardens for more than three decades — were notified they had to pack up and leave. According to the Miami Herald, Hialeah Pura Vida Commercial LLC and Hialeah Pura Vida Apartments LLC, the new owners, are going to build apartments on the 10-acre site. They offered the mobile home residents, some of whom paid at least $25,000 for their trailers, between $2,000 to $6,000 to relocate. Some of the Sunny Gardens mobile home owners took the deal, but a majority formed a homeowners association that negotiated a higher payout between $8,000 to $10,000 per home, according to a settlement agreement with the park owners. In recent months, the park has been cleared and a construction fence has gone up, but no building has begun.

Making a deal

At least one longtime park owner recognized the risk posed to residents by selling to a developer or institutional investor. When Everglades Lakes Mobile Home Communities sold its Davie mobile home park in July of last year to Zell’s Equity LifeStyle, the deal included an agreement that the buyer would not change the use of the property as a 55-and-up community for another 20 years. Equity LifeStyle’s shell company MHC Everglades Lakes also agreed to spend at least $3 million on capital improvements to infrastructure and common areas at the park within three years.

Raul Rodriguez, a majority partner in a company that owns the Li’l Abner Mobile Home Park in Sweetwater, said his family has owned the property at 11239 Northwest Terrace for almost 40 years and has no plans on selling it anytime soon. In January, Consolidated Real Estate Investments refinanced a $31 million loan with a new $52 million loan from Hunt Capital Mortgage that will allow the partnership — which includes Miami developer Sergio Rok — to make improvements to the site and eliminate old debt, Rodriguez said. “Yes, it is a lucrative business,” he said. “But from a morally conscious point of view, it would be extremely difficult to sell knowing all the people who live here would be displaced.”

Rodriguez says Li’l Abner’s 908 mobile home pads are fully occupied and more than 40 percent of the 3,500 residents have lived in the park for more than two decades. The site also includes an 87-unit affordable housing apartment building for senior citizens. “You can see the amenities we have put in that will challenge any high-end development that is out there,” he said. “We have five acres of green space, one of the largest pools in Miami-Dade, a clubhouse, tennis courts and basketball courts.”

Still, Rodriguez says the partnership is always willing to consider selling for the right price and a few caveats. “So far, nothing has come across the table for us to be financially happy with the offer,” Rodriguez said. “And there has to be a guarantee that there would be no displacing of the mobile home owners.”

Correction: This article has been amended to reflect that some residents in the Sunny Gardens mobile home park formed a housing association and received payouts of $8,000 to $10,000 per home.