A high-stakes battle unfolding in commercial real estate involves big Wall Street players and Elon Musk — and it’s not about his tweets.

As Musk was proclaiming in May that CRE is “melting down” and his since-renamed social media company was refusing to pay its office rent, Twitter’s landlord, Columbia Property Trust, was in default on loans that valued its portfolio at $2.3 billion.

That debt is held by Goldman Sachs, CitiBank and Deutsche Bank, and by bondholders who own pieces that were packaged into commercial mortgage-backed securities.

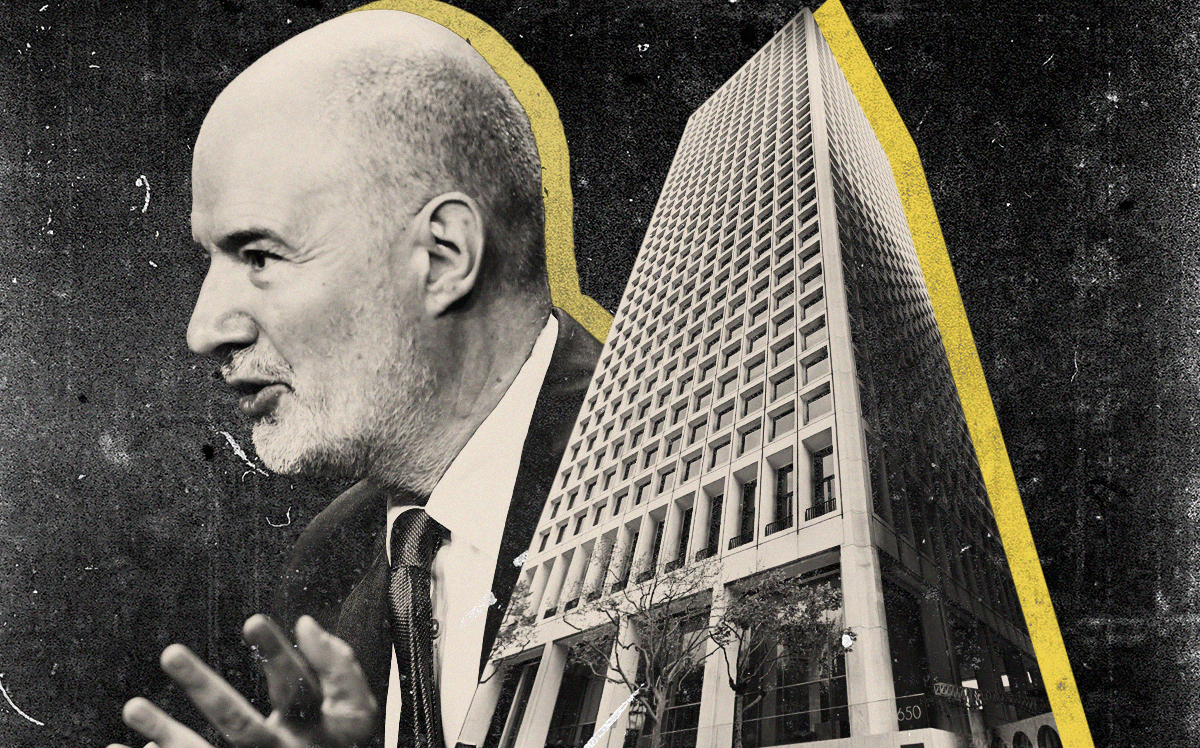

Also in the picture is Howard Marks’ Oaktree Capital, which is believed to hold the riskiest tranche of the CMBS, a position that put the famed distressed-debt investor in the driver’s seat to oversee a loan workout.

But a new appraisal this June valued the Columbia portfolio at just $1.6 billion, potentially devaluing Oaktree’s position so much that the company would lose its right to oversee the workout.

Oaktree, however, challenged that valuation and put forth a new one — $1.8 billion. The servicer overseeing the loan plans to accept that figure, putting Oaktree back in control of what’s shaping up to be one of CRE’s biggest power struggles.

“If you’re looking for a bare-knuckled fistfight in CMBS, this is it,” said Richard Fischel, a CMBS specialist at Brighton Capital Advisors.

As distress works its way through real estate, many of the equity investors have been cleaned out, leaving lenders holding the bag. But CRE lending is a different world than equity, with its own complex rules about who gets paid when — and who decides how it all shakes out.

The lenders overseeing the deals could end up getting valuable real estate for pennies on the dollar. And those forced to the outside could end up losing their shirts.

Tranche warfare

CMBS debt is stacked like layers of a cake, called tranches. At the top are pieces of debt that offer relatively low returns but the most security: The value of a property would have to fall near zero for those investors to lose money.

At the bottom are the riskiest pieces. These offer high returns but are the first to suffer losses when values drop. The last time wide-scale distress hit the CMBS market, following the Financial Crisis, the different classes of bondholders fought over control of upside-down deals in what became known as “tranche warfare.”

Such a barrage of litigation has yet to recur, but attorney Neil Shapiro at Herrick Feinstein sees signs that things are headed that way — not hired muscle, like in gangster films, but notices of valuation changes.

“You don’t send in goons when you’re a lender looking to take control,” he said. “There’s a lot of that going on now, where parties are asserting there’s been a change in the controlling class.”

One problem, Shapiro said, is that so few property sales are happening that appraisers lack data to determine what a portfolio is worth. The value ultimately decides who is in the controlling class, which is important because bondholders may have conflicting motivations.

For example, an investor who bought debt at a discount might be more willing to accept a discounted payoff than someone who paid full price and seeks to recoup the entire amount.

The Columbia Property Trust battle provides a window into the inner workings of CMBS distress.

When investment giant PIMCO bought the office REIT in 2021, it used $1.72 billion in loans. Oaktree owned the riskiest piece of the CMBS debt — the B-piece — as well as a $125 million mezzanine loan that sits outside the trust.

That puts Marks’ company on two sides of the negotiating table.

“When you have a mezz lender in the picture or a subordinate mortgage lender, that can complicate workout scenarios that can cause disputes kind of like what we’re seeing here,” said Patrick Czupryna, a managing director at KBRA Analytics.

An Oaktree spokesperson declined to comment.

A debt “coup d’etat”

These kinds of disputes are common in the byzantine structure of CMBS, where debt is sometimes split among a dozen or more investors. Now it’s happening in other areas of CRE finance as well.

In California, there’s a disagreement over who should make the decisions on the foreclosed $2.5 billion Century Plaza hotel redevelopment.

Urbanite Capital, a San Francisco-based real estate hedge fund founded by Mark Jorgensen and Steven Kay in 2017, claims that the U.K. billionaire Reuben brothers cut a deal that secretly subordinated Urbanite’s position in the debt stack.

Read more

The Reubens “successfully effectuate[d] a coup d’etat over the project’s mezzanine debt,” Urbanite claimed in a recent lawsuit.

Herrick’s Shapiro said the market is moving so fast that control of a workout can change quickly.

“Anybody who is in the controlling class today,” he said, “giving up [that position] is giving up a lot of control over the recovery of their investment.”