Gay Talese, 84, is already seated behind a six-inch tall coupe filled with gin and a twist when I arrive at our table at Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s restaurant in the Mark Hotel.

He had arrived a half an hour early for dinner. I watched him come in from where I stood at the near corner of the bar, drinking Mitcher’s on the rocks. Tall, lean and dressed nonchalantly to the nines, Talese had strolled through the bar, eyes focused on his target: the coat-check girl. He handed off his broad-brimmed fedora with a practiced gesture.

The bar at the Mark is dark, glistening and crowded with men who are, or seem very much like, Manhattan executives. In a place like that, Talese looks like some kind of rare bird. Yes, other men are wearing pin stripes, but not like Talese’s three, perfectly aligned suit pieces. Yes, other men have on yellow ties, but not in such vibrant silks. Talese’s plumage is a step above and you notice.

At our table, his ebullient wife, Nan, smiles to me across half a dozen oysters. She’s well known as a publishing executive, the senior vice president of Doubleday and the editorial director of her eponymous imprint, which has published the work of authors like Margaret Atwood, Ian McEwan, Jennifer Egan, Gus Van Sant and Thomas Keneally.

“How do you do?” she asks with an accent like a 1930s movie star. Talese tells me that “she spent some time in England,” but the inflection sounds pure New England boarding school. Together, the pair is the stuff of dinner party legends, although they seldom speak to each other at a small group dinner this evening. Instead, they keep two conversations going all the while, which occasionally collide and weld into a single chorus but for the most part remain distinct at opposite ends of the table.

A view into his parlor-level lounge.

For the better part of a decade, Talese has been writing “A Non-Fiction Marriage,” a book about their 57-year-long union, which has at times been tested by Talese’s famous and occasionally provocative “curiosity.”

Curiosity, he says, is essential for a non-fiction writer. He credits his own curiosity with a lifetime of success, from his job as a copy boy at the New York Times to a dozen books to magazine masterpieces like “Mr. Bad News,” “The Silent Season of a Hero” and “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” — which Esquire named the “Best Story Esquire Ever Published.” It also became a seminal piece of what writer Tom Wolfe identified as New Journalism, a method of reporting that employs the techniques of literature.

We meet again days after our dinner. “Do you think the Sinatra piece is what you’ll always be known for?” I ask, seated in the lounge of his townhouse on East 61st Street between Park and Lexington.

“I certainly want to be remembered for more than that,” says Talese, leaning down over his right shoulder to find eye contact despite our difference in height.

“Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” follows a rather disgruntled and fairly uncooperative Sinatra for weeks around Los Angeles. It’s comprised mostly of interviews with Sinatra’s retinue and captures an unusually intimate portrait, despite Talese’s lack of direct access to the great crooner. The article, which ran in the April 1966 issue of Esquire, had an overnight impact on journalistic style that is hard to imagine today. “That wasn’t even my best piece, I don’t think. Of course, I’m not the judge of that,” he adds.

That year was perhaps his most important. He signed a year-long contract with Esquire for six articles (of which he wrote five). The first of those articles, “Mr. Bad News,” is a profile of the rather obscure New York Times obituary writer Alden Whitman.

“It’s better than ‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.’ Why? Because it’s pure fiction,” or rather it reads like it, Talese says. “The thing I wanted to do was write like a fiction writer, while being absolutely accurate. ‘Mr. Bad News’ was like Melville’s ‘Bartleby, the Scrivener.’ It was really based on that.”

Talese says that although he is known for writing about criminals, athletes and celebrities, he prefers to focus on ordinary, unknown people “who are a little odd.”

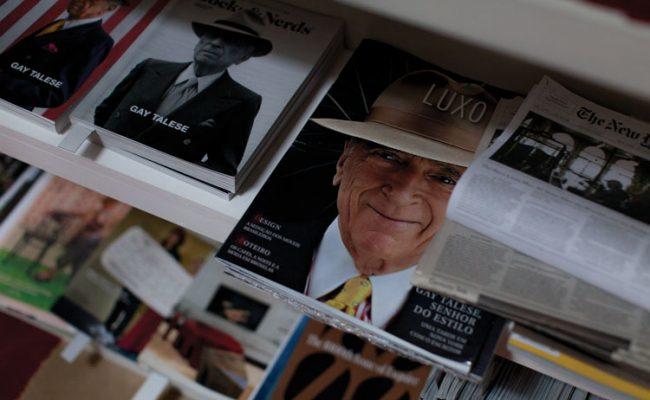

Magazines and newspapers featuring Talese

In the new sexual autonomy of the 1970s, curiosity and an interest in the intimate lives of common people drew Talese into Manhattan’s “Live Nude Model” massage parlors. He began frequenting establishments where he enjoyed receiving massages to completion from nude women — in part for research for his book on the changing sexual appetite of the American public, but also out of personal rebellion against the guilt born of his Catholic upbringing.

“Unlike the millions who casually masturbate in solitude while looking at girlie pictures in Playboy and similar magazines, the massage man preferred an accomplice, an attendant lady of respectable appearance who would help him reduce the guilt and loneliness of this most lonely act of love,” he wrote in the resulting book, “Thy Neighbor’s Wife.”

Norman Mailer, a close friend especially in his later years, didn’t believe in solo masturbation either, Talese tells me later. As for Gore Vidal’s sexual predilections, it was rent boys. “It’s a wonder Vidal never got AIDS. He’d just pick up guys off the street,” he says.

He went on to befriend many of the uninhibited young girls massaging their way through college and began managing Midtown massage parlors himself. More than the gangsters he would bring home for dinner while writing “Honor Thy Father,” his previous book about the Bonanno crime family, Nan objected to his bringing the masseuses and their lascivious boyfriends home to dinner. That was the final straw: “It’s your book, it’s your style of research. Leave me out of it,” she told him.

“The thing I wanted to do was write like a fiction writer, while being absolutely accurate.”

“I was seriously interested in obscenity. Nudity was shocking. Of course, it was breaking into pop culture little by little with ‘Hair’ and ‘I Am Curious (Yellow),’ but it was still in the area of scandal. And I was scandal. I was Mr. Scandal himself,” he said, referring to a controversial and personally hurtful 1973 profile in New York Magazine titled, “An Evening in the Nude With Gay Talese.” The interview took place in a nude health spa and involved not a little hanky-panky. The piece ends with Talese, arm in arm with his nubile companions, marching merrily off to an orgy.

“I was a married man, with two children,” Talese said. “My wife is a respected editor. I had a reputation as a serious writer. And here I am frolicking with a masseuse in a private club where you could swim in the nude and get massages. And I was running two massage parlors myself. What I thought hurt me was that it looked like I wasn’t serious.”

In retrospect, the New York Magazine piece doesn’t have the same bite today. If anything it feels a little cliché, like a scene from “Caligula.”

“No one cares today,” Talese agrees.

His newest book, which is due out this summer, once again visits the seamy side of American sexuality, this time via mid-century, drive-in motel culture. Talese calls it a book on voyeurism. (I was asked not to reveal the name of the book, which will be excerpted in The New Yorker in the spring.) He explains that motels are a symbol of how times have changed.

Talese descends the stairs outside his home.

“Today you can go to the Regency Hotel and sign in with some pole dancer and no one will give a shit,” he said. “But in the 1950s and ’60s people would sneak in and out of motels if they were having affairs. You would pay cash and use a phony name.”

We switch to wine and Talese wants to order. It’s almost 10 p.m. He also wants to know how magazines like ours make money today. “What are you selling?” he asks again and again. He’s a journalist by instinct. He prefers to listen and let others lead the conversation, occasionally piping in with questions. He takes notes throughout dinner on shirt boards cut into ovals so that they fit neatly into his jacket pocket. Shirt boards are his signature. He’s taken notes on them for decades for countless stories for The New Yorker, The New York Times and Esquire. He still won’t use a recorder.

He says that for him writing is like tailoring clothes. It’s all neat stitches. It’s all truth, researched and experienced. That’s not “New Journalism,” he argues: “New Journalism is just something Tom Wolfe made up. It doesn’t mean anything.”

He comes from a line of Italian tailors. His father was a tailor and his cousins are Paris-based couturiers. He worked in his father’s shop in Ocean City, N.J., as a boy, and it’s where he learned manners and style — things almost forgotten today that will get you far as a reporter, he assures me. I fiddle with my cufflinks, suddenly self-conscious.

“Appearances are so important,” he reiterates during my visit to his home. He slouches back into the Chesterfield sofa in the parlor-level lounge, propping his feet up on the coffee table. He’s wearing a black, three-piece pin-stripe suit, a Cartier watch (the same one he wore to dinner three days earlier) and rich leather shoes.

On the top floor of the townhouse something like 100 tailored suits, many made by his cousins in Paris, hang behind wall-length, mirrored closet doors. Each one has a labeled hanger with the name of the tailor and a description of the suit. Down the hall, a walk-in closet contains nothing but hats and ties. Again, each hat is carefully hung next to a descriptive label: “4 – Dark blue fedora (made exclusively for Gay Talese by Puerto Fino) (only blue hat in Gay Talese’s collection of 30 hats).”

A drawing by Morley Safer in memory of their mutal friend Kurt Vonnegut

“It’s all about attention to detail. I’ll show you downstairs. It’s even more excessive,” he smiles.

Downstairs is what Talese calls his bunker. It’s an apartment-sized wine cellar converted into an archive and office that can only be accessed from the outside of the house. It’s where he does the majority of his work. Inside, Talese stores every scrap of research and every calendar from the last 60 years in cardboard file boxes. They are stacked floor-to-ceiling and plastered with collaged headlines and cut out photographs. Inside the boxes are chronological files that are themselves decorated with newspaper collages. Peeking out of file 1966, I see the outline for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.” “This is a great way to waste time,” he says.

In another corner he shows me a box of calendars going back to the 1950s. Each day is filled with information: who he met, where they ate and even how much dinner cost. Yesterday evening, dinner was with celebrated postmodern fiction writer Don Delillo, he says. “He’s a very quiet man,” Talese recalls.

The bunker is an obsessively curated time capsule. It’s Talese’s most sweeping project. It’s a work of living non-fiction. The same is true, he says, of his four-story home. He has lived in the building on East 61st Street for 59 years, piecing it together from a collection of rent-controlled apartments into a museum-quality mansion, where eminent names of the last half-century — like Norman Mailer, Gabriel García Márquez, Frank Stella and Michael Bloomberg — have paid a call.

“In one house you have a lot of stories simultaneously being experienced and lived. It’s almost like a ship at sea. You are floating and you have all these cabins that are filled with not only people but with memories and histories,” he says. “In this building you have the stories of the former tenants — the model who ran off with the director [Otto Preminger] and her two blind dogs, the airline stewardess who left her toaster on and burned the damn fourth-floor apartment and the widow of French harpist Carlos Salzedo” who filled the house with music.

“Appearances are so important.”

Talese rented his first apartment in the house in 1957. It’s a long time to live in one place, but he insists that very little about his block, and for that matter the city, has changed. “I don’t subscribe to the notion that all the artists are being driven into the hinterlands by the greedy landlords,” he says. “I think it is hard, but it has always been hard.”

“When I look out the window, I see a block that is architecturally the same as when I first arrived here,” he adds. Even in the 1970s and 80s, the city’s dark days, the crime and vandalism never found his block. It never got worse than a few overturned street planters, he says.

Leaning in close to fight the noise at the Mark, Talese tells me what is different about New York today. “Life was a little harder for my generation. We were not that formally educated,” he says.

Talese graduated from the University of Alabama and one of his most charming attributes is the pleasure he takes in shocking well-bred New Yorkers, who feel an inherent sense of superiority over Southerners, with his fondness for his years there.

“I had terrible grades. It was the only place I could get into, but it was a great experience,” he says. Years later, in 1965, Talese returned to Alabama to cover the civil rights march at Selma for the New York Times. He says he goes back to Alabama often today.

But, in a city obsessed with the Ivy League, new Manhattan acquaintances struggle with the idea of attending a less-prestigious school. Alabama might as well by Kyrgyzstan.

“In the 1953 I started working at the New York Times, and the people around me were not that educated. We were not from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, we were from places like the University of Alabama, Fordham if you were Irish, or City College if you were Jewish. And their parents didn’t go to college. They had fathers who were labor leaders and mothers who were seamstresses. Black people were the children of laborers. Today, young journalists are the children of people who went to college. So they do not necessarily have the familiarity with poverty. They grew up in better circumstances,” he says.

“I often give guest lectures at Yale, Harvard, Columbia or NYU, and I’ll address a group of 30 or 40 students. They’ll complain about how hard it is to get a job. But when you get out of college you don’t really know that much and getting a job at a newspaper, you have to live a little bit first. They are more comfortable and more entitled to the good life.”

Talese, who prefers to write long hand, has never embraced so-called “new media.” In fact, he blames technology for the decline of class-conscious reporting.

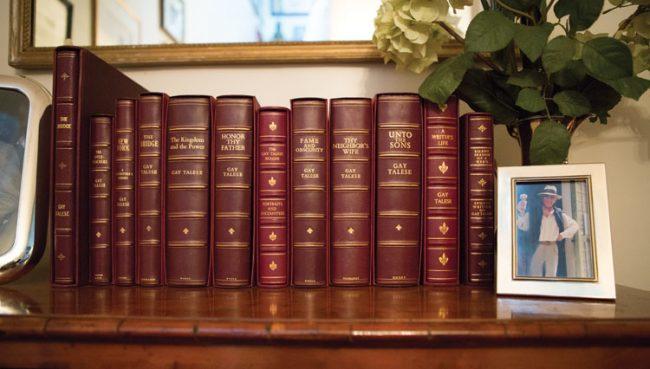

Leather-bound editions of Talese’s books.

“Young journalists are all so hooked on technology they don’t see the underclass,” he says as I finish my cod. “Journalists don’t write about the underclass because they aren’t comfortable with the underclass. They are so removed from the experiences of their ancestors. God! They don’t go out and experience anything. They are goal oriented. They never discover by chance. The idea of serendipity doesn’t exist.”

Talese orders dessert. Nan abstains. And I have an ill-advised brandy. Tipsy and energetic as the clock nears midnight, we discuss Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal until Talese says goodnight.

Back at the bar, the executives, their collars now unbuttoned, are starting to thin out. I order a Lagavulin 16 as I replay our conversation in my head. A pretty brunette from a back table introduces herself by pressing in close and whispering in my ear. I pull back a little, surprised. She tries again, touching my chest and feigning intoxication. I can feel her lips grazing my ear as she suggests that we find someplace else to go. Eliot Spitzer is said to have met his $1,200-an-hour call girls here.

“I don’t have any money,” I say more bluntly than I intend.

“Oh, don’t say that,” she says, putting on a pouty face.

Eventually, a plump blonde girl in a large white fur coat appears to collect her friend. I realize that I was being watched the whole time and I am suddenly very glad that I am not up for a bit of embedded reporting. Talese is right, you don’t get any of this with a phone interview.