From the archives: Cindy used to dream of barging through the front door of Bar Works West Village, TV crew in tow. She would stride past the bar up to the managing director, a barrel-chested man whom she only knows from online videos, and bombard him with questions. Why didn’t he respond to her emails and calls? What did he do with her money? And where can she find the mysterious “Jonathan Black?”

An Australian in New York, Cindy, who like many other victims only spoke to The Real Deal on the condition that her name be changed, is one of more than a hundred investors from around the globe who lost their savings to what appears to be a bizarre fraud. On the surface, Bar Works is just another co-working company. Wedged between Seventh Avenue and Morton Street, with large windows and arching brick walls inside, the street-level space could make for a quaint restaurant. Instead it’s got bland desks dotted with telephones, wheely chairs covered in gray velvet, and a fully-stocked bar. It calls itself a “workspace with vibe,” a fair description if the vibe you’re going for is a cross between a WeWork, a dive bar and an airport terminal.

This is the single biggest calamity that’s ever happened to me. And I’m 68.

In reality, however, the space, along with other Bar Works locations in Manhattan, Brooklyn, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Miami and Istanbul, looks to have served as a front for Renwick Robert Haddow, a British career fraudster. Through a labyrinth of agents and websites, of emails and social media ads, Haddow and his associates orchestrated a global fraud scheme, sources said.

The pitch to Cindy was compelling: Bar Works would rent or buy retail spaces, turn them into offices with a bar and sublet desks to the creative class. It needed to raise money to fund its expansion, so it offered investors the chance to buy a desk in one of the spaces and get a slice of the rent. And it guaranteed double-digit returns.

Haddow went through great lengths to mask his involvement, installing his Ukrainian wife as a co-founder under a pseudonym. Most investors were in the dark until TRD exposed Haddow’s role in January, and even then some held out hope until payments started drying up in March and April.

In the world of scams, Bar Works is relatively small. But it is a perfect example of why real estate investment fraud is on the rise around the globe, bolstered by the spread of e-commerce and social media, the lack of an international enforcement authority, the complex nature of development projects, and investors’ thirst for outsized returns.

In hindsight, Sarah*, who lives in North Carolina and works in the technology department at a major insurer, isn’t sure how a London-based company called United Property Invest got her email address. But that didn’t matter at the time. What mattered was the lure.

“Investors like you are generating a monthly income of up to 16% Pa From Our Two Coworking Spaces On W39th Street and W46th Street close to Times Square,” the email read. She put in $300,000.

For Ruth*, a British retiree, it began with a “very slick” Facebook ad by an investment agency called Heron Global Partners. First, she invested in a wind power project. Then, she gave the rest of her savings to Bar Works and persuaded several family members to invest as well.

“A burglar who’s come into my house and stolen all my stuff,” is how she described the agent who convinced her to invest. When TRD requested a second phone call, she insisted on the cheapest option, Skype. “I don’t have any money,” she said with a slight laugh.

Bar Works West Village

“This is the single biggest calamity that’s ever happened to me,” she added. “And I’m 68.”

Haddow and Bar Works did not respond to calls and emails seeking comment.

On June 30, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York unsealed separate fraud charges against Haddow. Prosecutors claim he raised more than $36 million from Bar Works investors and wired $16 million to foreign bank accounts that were likely tied to him or his associates. They also allege he ran a separate scheme, Bitcoin Store, that promised high returns from investments in the virtual currency. Haddow faces up to 40 years in prison — if he is caught.

Why join the Navy if you can be a pirate?

“There’s always a type of investment fraud that’s the flavor of the month,” said David Marchant, a journalist who runs the news site OffshoreAlert and has been tracking financial fraud since the 1990s. In the past it was day trading, foreign exchange deals or bank guarantees. But in recent years, Marchant has noticed an increase in real estate scams.

Real estate is an ideal target for con men. It’s easy to explain to lay investors, is popular in major emerging economies like India and China, and has a reputation for stability. But large-scale fraud in the sector could never have taken off were it not for the confluence of two key trends. The first is central banks pumping cash into economies around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. There is now more capital than ever seeking investments while interest rates are near record lows in most countries.

“If you go to the standard investments you really get little value out of your money,” Sarah said, explaining her quest for alternatives.

The second trend is digitalization. In 2010, about 30 percent of the world’s population had internet access. By 2016, that number had hit 47 percent, according to data from the International Telecommunication Union. During the same period, the number of Facebook users rose from 608 million to 1.86 billion, according to Statista, opening up a giant new avenue to market online real estate investment.

In the U.S., dozens if not hundreds of crowdfunding platforms now allow small-time investors to buy properties they have never seen and may not understand within just a few steps online. A global maze of lightly regulated online investment agencies, many of them based in the London, market properties to investors.

Proponents argue that they are democratizing investment, and they have a point. A decade ago, it would have been very difficult for an upper-middle-class saver in India to buy a flat in Hong Kong or a condominium unit in Miami.

But the internet also opened the door to fraudsters. For this story, TRD spoke to people from places like the U.K. and Macau who said they fell victim to U.S. real estate scams after clicking on Facebook ads. Dan Johnson, whose OPP Ventures advises real estate marketing platforms on lead generation, said social media has made it “much easier to get exposure” for scammers. Rather than make cold calls, agents now buy names, email addresses and social media profiles in a “murky world of data acquisitions,” Johnson said. Anyone who has ever so much as clicked on an investment ad or made an email inquiry could see her contact information sold.

In 2016, the media agency Grain was nominated for a digital industries award for an ad campaign on behalf of Heron Global Partners, the firm that Ruth invested through. “By profiling the target audience, Grain was able to collect a granular level of demographic and psychographic information,” the awards website notes. “In just six months, HGP had transformed its customer acquisition strategy, increasing revenue by 578% and achieving an ROI of 3276%.”

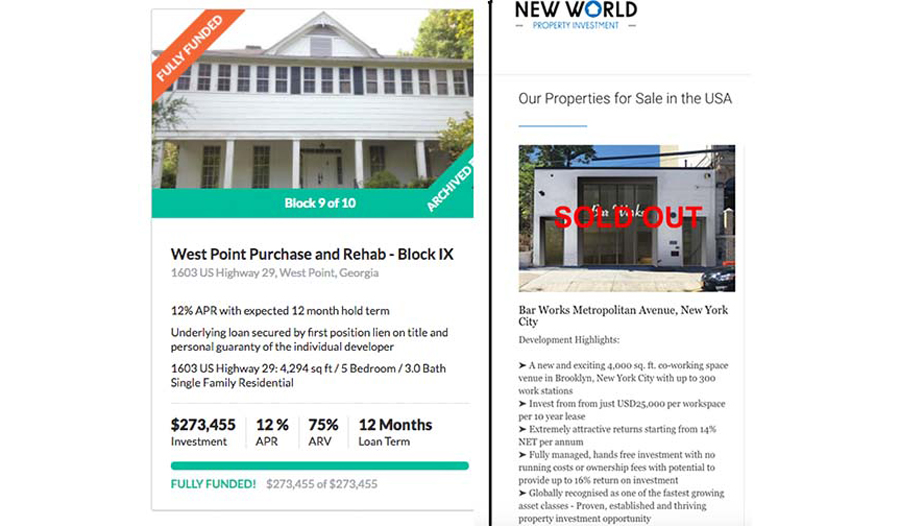

Fraudsters often mimic legitimate investments. The image below, for example, shows two online investment offerings. The one on the left is a fix-and-flip property investment, marketed by the California-based crowdfunding platform Patch of Land. It is risky, hence the 12 percent return, but offered by a well-known company with a credible track record. The one on the right is an ad for Bar Works. To the untrained and return-hungry eye, it’s hard to tell the difference.

From left: an investment ad by real estate crowdfunding company Patch of Land and an ad for Bar Works

In this sense, the rise of online real estate investment fraud is part of a broader phenomenon: the deliberate spread of false information through social media. Much like Russian hackers used Facebook and Twitter to share fake news stories prior to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, scam artists have increasingly powerful tools to spread and cash in on disinformation. It’s finance for a brave, new, Trumpian world, where facts and numbers can be alternative.

Petter Bae Brandtzaeg, a research scientist at Norway-based SINTEF Digital who specializes in the veracity of online news, said people behind science scams often use the same kind of heavy social media promotion as the people behind fake news, and that these tools are just as useful for other cons.

“People using social media also experience a context collapse of news, fakes and facts which makes them vulnerable to these scams,” he said.

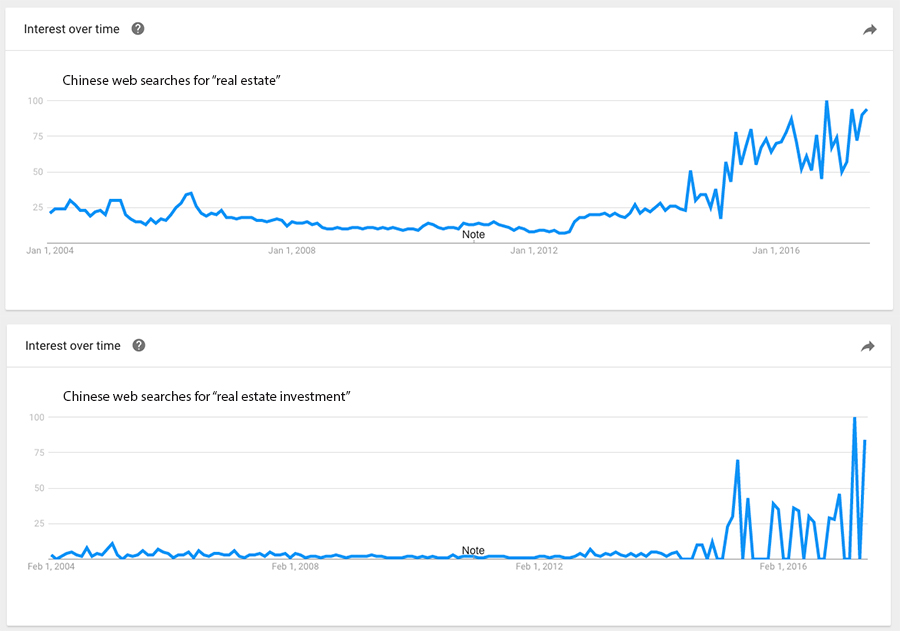

Figuring out how much money is lost to real estate fraudsters around the globe is virtually impossible because most operate in unregulated markets and very few ever get prosecuted. But Google data shows how the potential market for online investment has grown.

The global monthly average number of internet searches for “real estate investing” rose to 33,100 in May 2017 from 18,100 in June 2013, according to data provided by the digital marketing firm Mondovo. Searches for “buy to let” rose to 18,100 from 12,100 during the same interval. The increase is even more dramatic in some developing countries. In China, for example, by far the world’s largest emerging economy, searches for the term “real estate” have grown around tenfold since 2012, Google Trends data indicate. Through targeted ads, fraudsters can lure people who search for these terms to their websites (at least 27 Bar Works victims are from China).

Google search volume for the terms “real estate” and “real estate investment” in China. (credit: Google Trends)

TRD identified 16 different websites that have marketed Bar Works, with names such as FJP Investment, Gateway2enterprise and New World Property Investment. The total number is likely much higher. Most were based in London, but the investors they lured to Bar Works were from countries such as Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong and the U.S. Some of these websites served solely to market Bar Works, while others offered it along with hundreds of other real estate deals.

In theory, agents are responsible for vetting investments. But in reality, they are either part of the scam or they don’t care. Fraudsters tend to pay agents unusually high commissions, often as high as 25 percent, according to sources.

“The more ridiculous the scheme, the higher the commission,” OffshoreAlert’s Marchant said.

Cici Cao, a Keller Williams agent in New York who put a local investor in touch with Bar Works for a 15 percent commission last year, said she never suspected the program might be a scam. It was up to the investor to judge the risk, she insists.

“I also feel like I was a victim of this,” she said.

Agents often target overseas customers, which helps shield them from legal liability if an investment turns out to be a scam. At any rate, small-time investors often don’t have the financial means to sue. This means agents have little to lose from selling questionable investments as long as they can credibly deny knowledge of fraud. The result is a culture of don’t ask, don’t tell.

“Real estate fraud doesn’t happen usually without some sort of systemic failure on the part of third parties,” such as banks, brokerages or law firms, “who are supposed to be gatekeepers,” said Joshua Kons, a Chicago-based securities and investment fraud attorney.

Take Square Yards, an Indian online real estate investment platform that recently raised $10 million in venture and debt funding from big names like L’Occitane vice chair André Hoffmann. The firm sold investments in at least two U.S. real estate scams (one being Bar Works) to investors in the U.A.E. and Hong Kong.

Tanuj Shori, CEO of Square Yards, said his agents received an 8 percent commission for selling Bar Works investments, but only dealt with the company through another middleman. Sources said this was a common path for real estate fraudsters, who regularly go through two, three or even four layers of agents.

Tanuj Shori

Shori claimed he had never heard the name Renwick Haddow until he read it in TRD. Asked why Square Yards didn’t do basic due diligence on the offering, such as checking if the supposed principals even exist, he said it was an “honest mistake” by a young company.

“Our entire reputation is at stake because of Bar Works,” he added. But when asked whether he would reimburse the victims, he said that’s an issue between Bar Works and the investor. The company later sent an email to its clients claiming it is “retaining an independent investigator to search for useful information about Barworks and its owners as well as assets that may be recoverable.”

Shori claimed that Square Yards stopped marketing Bar Works shortly after TRD’s January report. He painted himself as a victim of Haddow’s. But emails sent to one investor and reviewed by TRD suggest otherwise.

Kamal Singh, a 32-year old engineer, first invested $60,000 with Bar Works in August 2016. He had moved to the U.A.E. from India in 2012, and Bar Works seemed like a shortcut up the ladder.

As the returns started coming in, Singh decided to up his bet. There was just one problem: he had already spent all his savings. In a mid-February meeting, a Square Yards executive suggested a solution: Singh could take out a $100,000 bank loan to buy up to 10 desks at Bar Works’ planned location in Istanbul (Square Yards denies it suggested the loan, claiming it was Singh’s idea).

As Singh waited for bank approval, the executive’s emails gave the impression that the desks were being snapped up fast.

“They had strictly given me a one-week window,” he wrote on March 2. “Pls transfer asap when you get the funds.” Shortly after, Singh got a $90,000 loan and bought more desks. In April, his return payments didn’t come. In May, he says Square Yards and Bar Works stopped responding to his increasingly exasperated emails. Singh wants to sue both, but said he doesn’t know how. Now his loan payments are due and he has no way of paying them.

“I am in deep trouble,” he wrote in an email. “Don’t know what to do.”

“Nobody gives a shit, that’s the harsh reality of life”

At some point, every fraud unravels. But rarely is the perpetrator held accountable. Few people illustrate this better than Haddow.

Born in 1968 and reportedly educated at Thames Valley University, he first popped up in 2002 up as the operator of so-called Cosmopolitan Spirit cafes in the U.K., borrowing the brand of the well-known magazine for bars geared at women. He began raising money from investors, ostensibly to fund the company’s expansion, but ran into legal trouble. In December 2008, the U.K. insolvency service banned him from running any company for eight years, in part because he had made false statements to investors, didn’t keep proper accounting records and paid investment agents 25 percent commission.

The more ridiculous the scheme, the higher the commission.

The ban didn’t stop Haddow from building a vast global Ponzi scheme around the sale of carbon credits, African land, Eastern European hotel rooms and other so-called alternative investments. A 2015 investigation by the World Policy Journal found the scheme sucked up an estimated $180 million from investors, many of them retirees.

In February 2014, the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority won a court ruling that Haddow’s schemes broke the law, paving the way for a potential future criminal case. Later that year, Haddow and his girlfriend (now wife) Zoya Kiselova moved to New York, renting an apartment at 3 Lincoln Center, company records and StreetEasy data indicate.

Renwick Robert Haddow and Zoya Kiselova

In 2015, Bar Works launched. Haddow was careful to keep his name out of any advertising documents and news reports. Officially the company’s co-founders were “Jonathan Black” (there is no evidence he exists and Bar Works’ managing director Franklin Kinard later told journalists that Haddow made the name up) and “Zoe Miller” (Haddow’s wife, Zoya Kiselova). But TRD traced Haddow’s involvement through sources, liquor licenses signed by him and Bar Works entities registered to his apartment.

That Haddow was allegedly able to run scam after scam for 15 years, first in London and then in New York, is far from unusual. “In the real world most fraudsters get away over and over again,” Marchant said. Regulators tend to be understaffed, fraud can be difficult to prove, and there are simply too many schemes going on at any given time to investigate them all. In her 2012 book “The Ponzi Scheme Puzzle,” legal scholar Tamar Frankel claims that Ponzi schemes, most of them small, cause about as much financial damage each year in the U.S. as shoplifting. And they are about as tough to eradicate.

Investors can use the courts, but first they have to figure out whom to sue, and where. Take Singh, the U.A.E. resident. His investment in Bar Works was made through an India-based agency, which in turn dealt with Bar Works through a mysterious middleman with a British accent who went by the name Julian Tzanev, according to Shori. To complicate matters further, Singh received a “certificate of ownership” from a Delaware company called Bar Works Inc., signed an investment agreement with Istanbul-based Bar Works Istanbul LLC, but signed a separate contract to receive his monthly returns from yet a third company, Bar Works Management Inc. And when it came to returns, investors received them from a U.K.-based account. Much of Singh’s money may be with Haddow, who has denied involvement in any of the above entities and is known to stash his wealth in offshore tax havens like the British Virgin Islands or Anguilla.

Even when regulators do get involved, investors are unlikely to get their money back, as the case of a recent North Dakota real estate scam illustrates.

In April 2015, the SEC filed a complaint against North Dakota Developments LLC, alleging that it stole $62 million from more than 970 investors in a Ponzi scheme. Starting in 2012, the company raised money to build temporary housing for oil workers in North Dakota, but most of the buildings were never completed. According to the SEC, the company used payments from later investors to pay off earlier ones. Like Bar Works, NDD had marketed its investments through online portals, such as a U.K.-based company called United Property Connect, which appears to be connected to United Property Invest, the company that Sarah had invested through.

The SEC put NDD under receivership and froze its assets, but there was little left to freeze. The people behind the scam, a U.K. resident named Daniel Hogan and Malaysia resident named Robert Gavin, were safely out of the country with their loot.

In July 2015, investors filed a class action lawsuit against a U.S. based law firm that had worked as an escrow agent for NDD (another suit had been filed in June). They managed to win around $5.1 million in a settlement — a fraction of the $62 million lost. According to Kons, who represented the investors, that still compares favorably to other international frauds – victims generally get little to nothing back.

“The SEC only has so much jurisdiction and when the money’s overseas there’s little they can do,” Kons said. “It’s just very difficult to bring these guys to justice. White-collar crimes and white-collar fraud are just under-prosecuted.”

Zoya Kiselova’s Facebook post about meeting the infamous financial fraudster Jordan Belfort

There is no global authority to fight financial fraud. When U.S. prosecutors issue arrest warrants for suspected fraudsters, they can share them with Interpol but have to rely on other countries’ co-operation. Michael Goldberg, an attorney at Akerman LLP, said he has seen financial fraudsters extradited to the U.S., but doing so is “challenging” and they are typically U.S. citizens. He said he has unearthed funds from places like the Cayman Islands, in part because tax havens have become more cooperative in recent years amid U.S. pressure, but conceded that it’s not easy.

To Marchant, cases like NDD show that the global offshore financial markets are tilted in favor of debtors. They allow tax evaders and fraudsters to hide, leaving their victims in the cold.

“Nobody gives a shit,” he said. “That’s the harsh reality of life.”

“I think he was really surprised I knew what hotel he was in”

One of NDD’s victims is Lam, a 45-year-old schoolteacher in Macau who only agreed to share his surname. Shortly after investing in the scheme, he decided to double down and find more real estate investments.

In mid-2014, he saw an online ad for high-yield real estate investments in the Chicago area. The company, KRI Property, claimed to have relationships with U.S. lenders allowing it to buy foreclosed homes on the cheap and flip them. It guaranteed 30 percent returns.

Unlike NDD’s risky ground-up developments, this seemed like a safer bet to Lam. He would be buying an existing home, and even if the flip didn’t work out he’d still own a property. He borrowed $60,000 from his sister and invested.

KRI turned out to be tied to InvestUS, a scheme run by James Jervis, a 39-year-old U.K. native and Dubai resident who was an old hand at the game of global real estate fraud. His victims claim he never actually bought any properties with their money. They received deed documents signed by Chicago-based attorney Alex Ogoke, but they appear to be fake. One document reviewed by TRD references a sale that doesn’t appear in Chicago property records. Ogoke initially agreed to an interview, but later changed his mind, citing a death in the family. Jervis did not respond to an email seeking comment.

While Haddow took pains to keep a distance from his investors, Jervis did the opposite, sometimes meeting them in person to assure them money was coming. One of the victims, a 72-year-old South African former merchant ship captain named Al Viljoen, said Jervis even stayed at his home on several occasions. Viljoen says he lost his retirement savings, around $130,000, and had to go back to work full-time to make ends meet.

Regular facetime with his victims could prove to be Jervis’ undoing. Earlier this year, a friend of Oman-based Ahmed*, who says he invested $300,000 with InvestUS after clicking on a Facebook ad, came up with a plan to lure Jervis into the country to face prosecution. The friend offered Jervis a follow-up meeting with a prospective investor in Oman. Jervis took the bait, hopped in a car and drove to Muscat from the U.A.E. Meanwhile, Ahmed filed a fraud complaint with the Omani government. As soon as Jervis entered Oman, the authorities slapped him with a travel ban.

Stuck in Oman while his case moves through the justice system, Jervis has been bouncing from hotel to hotel, according to Ahmed, who is keeping track of his movements. One day this spring, Ahmed confronted him at the door of his room. “I think he was really surprised I knew what hotel he was in,” he said. “He looked as if he hadn’t slept in days.” Their conversation was brief and Jervis looked away whenever he said he had no money, according to Ahmed.

James Jervis

Omani government agencies did not respond to several emails and phone calls seeking confirmation of the travel ban and fraud case against Jervis.

Whether Ahmed’s case succeeds is far from certain. And even if it does, it likely won’t help Lam, whose situation is far beyond Oman’s jurisdiction.

After finally losing patience with Jervis last year, Lam, like Ahmed, decided to take matters into his own hands. But he soon discovered his options were slim.

First, Lam called the police in Ireland, where the agent who had sold him his investment was supposedly from. The police told him it could only help him if he was an Irish citizen or traveled to Ireland to file a complaint in person. In November 2016, Lam went to the Macau police. The officer told him there was little they could do since Jervis and the company that had allegedly defrauded him were both overseas. He then filed a complaint with the FBI but never heard back. At one point he called the Chicago police, who told him they couldn’t help him because he’s not a U.S. citizen.

Lam said he has lost around $400,000 to dubious online investments — more than his life savings — and is currently paying off his sister’s loan with his modest teaching salary. He considered hiring a lawyer, but is loath to throw more money down the drain. “Other than being depressed, what else can I do?” he said. “I have no idea how to get help.”

Exit Renwick

While Jervis was trapped in Oman, the noose started tightening around Haddow in New York. After two months of missed payments, a group of Chinese investors filed a lawsuit against Haddow, Black and nine Bar Works entities on June 16 in state court, alleging he defrauded them out of more than $3 million. On June 21, another investor, Plentium Capital Group, filed a fraud lawsuit in Florida federal court. On June 28, New York attorney Jared Stamell told Crain’s he is considering filing a class-action lawsuit on behalf of 200 investors who gave $30 million to Bar Works.

The audience is investors as well as engineers so a mixed level of expertise but let’s try to avoid the jargon.

By that point, the FBI was already investigating Bar Works. And worse for Haddow: Kinard, who had left the firm in May, appears to be cooperating. He told attorneys that FBI agents called him in mid-June and that he “communicated vigorously” with them. He claimed to have no involvement in investor negotiations or knowledge of where the money went. “My electronic signature was placed on investor contracts without my knowledge,” he wrote in an email filed in court records. Kinard and an FBI agent working on the case did not respond to TRD’s calls.

As courts began freezing assets, lawyers for the plaintiffs searched for any money they can recover. There may not be much. According to Kinard, Bar Works only had one U.S. bank account, with Valley National Bank, which held less than $30,000 as of mid-May.

On June 20, Adam Birnbaum, one of the attorneys representing the Chinese investors, walked into the lobby of 160 West 66th Street, where public records indicated Haddow rented an apartment, to serve him with the lawsuit. The receptionist told him Haddow had recently moved from an apartment on the 33rd floor to a unit on the 19th floor but abandoned that apartment at the end of May. Haddow called in mid-June to tell the receptionist he would come to pick up his mail, but never showed up.

A day later, on June 21, a legal server rang the doorbell at a Greenwich, Connecticut, home that Haddow appeared to rent. A woman opened the door. She refused to give her name and said Haddow was away. When Birnbaum showed the server a photo of Kiselova, the server identified her as the person who answered the door. Ten days later, the SEC and the U.S. attorney’s office unveiled their fraud charges.

At the time of writing, Haddow remains on the run. But wherever he is, he appears to be already thinking about his next venture. In mid-May, a person who called himself Robert and used the email address info@barworks.nyc hired a New York-based IT consultant to write a report on the “future of email services.” Robert wanted the report to include research on “how email of the future can charge for their services and make money and also get a good take up.”

“The audience is investors as well as engineers so a mixed level of expertise but let’s try to avoid the jargon,” Robert added in emails the consultant later shared with TRD on condition of anonymity. Robert paid the first half of the $2,000 fee up-front — in Bitcoin. That’s when the consultant grew suspicious.

Through a tracker in a shared document, the consultant traced Robert’s phone to a location somewhere in Brooklyn and found that he also used the email address roberthaddow100@gmail.com. On June 6, he sent an email asking Robert for his Linkedin profile. Robert referred him to the website of his company, Bar Works. Then the consultant suggested he use PayPal rather than Bitcoin to pay the second half of the fee. He also asked for Robert’s full name. Haddow responded: “We are done here.”