It’s 1999. AOL is how most people receive email, and computers everywhere could soon succumb to the Millenium bug. It’s also the year when a new lender emerges and quickly gains a reputation for catering to wealthy clients with “complicated” personal finances. Its name? Bank of Internet.

Flash forward to 2018. The bank has rebranded to BofI Federal, emerged unscathed from a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation, and has made a major bet on a niche corner of New York commercial real estate — backing projects from some of Brooklyn’s most prolific Orthodox Jewish developers. It does this mostly by acquiring senior notes on loans originated by other funds.

Lately, the bank has been in the headlines for a pair of real estate loans tied to Kushner Companies, as ProPublica reported. At Toby Moskovits’ Bushwick office redevelopment at 215 Moore Street, BofI refinanced the last-known Brooklyn development loan held by Kushner Credit Opportunities Fund, a debt vehicle Kushner Companies founded in 2016. At One Journal Square in Jersey City, BofI put up funds to finance Fortress Investment Group’s $57 million bridge loan to Kushner Companies. That two-tower project has been plagued by problems, both political and financial, and it’s unclear if the company will be able to see it through.

In an interview with The Real Deal, Gregory Garrabrants, BofI’s CEO, said it was misleading to draw any connection between his firm’s business with Kushner Companies and the fact that the SEC investigation was dropped.

“There’s a political agenda behind talking about Kushner,” Garrabrants said. “I don’t know Mr. Kushner, but I don’t have to because we know Fortress.”

Deep Brooklyn

Though BofI, a San Diego-based company with $8.9 billion in assets, has long been active in single-family lending in New York, it only recently got into commercial real estate. Sources said it started to appear as a financing option in “warehouse lending,” in which a bank issues a loan to a warehouse owner and funds that loan with debt from a secondary lender, such as BofI. Essentially, it’s a way for lenders to issue loans without having to use their own money. This type of deal is often referred to as loan hypothecation, in which the original loan is the collateral for the debt a lender seeks from a bank.

“It’s more of a West Coast thing,” said David Eyzenberg, an investment banker, on the hypothecation structure. “Where we really got to know [BofI] was in providing leverage to hard-money lenders.”

The bank’s services have been especially appealing to developers in Brooklyn, specifically the middle-market investors and luxury rental builders hailing from the borough’s ultra-Orthodox communities, according to an analysis of property records by TRD. The analysis found that of Bofl’s 10 largest loans backed by real estate in the last three years, eight were tied to assets owned by Brooklyn developers, including a number from Williamsburg’s Hasidic community.

Hasidic developers commonly prefer to finance in smaller loan increments over several stages, allowing them to revise design plans or recapitalize with additional partners and then restructure the financing, sources said. The approach stands in contrast with Manhattan’s development giants, which traditionally shoot for a large institutional loan up-front.

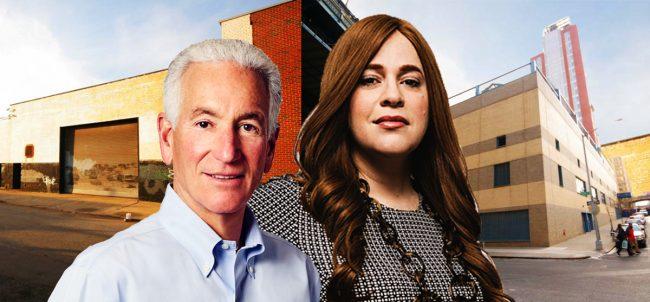

Charles Kushner, Toby Moskovits, 215 Moore Street and 61 Adams Street

“There is a certain type of sponsor turning to this bank for land and development deals, which have a higher cost of capital and are harder to finance,” said an investor familiar with the bank who requested anonymity. “And so the bank has largely been serving as a bridge lender to the same players.”

The list includes prominent Hasidic builders such as Simon Dushinsky’s Rabsky Group, Abraham Leser’s Leser Group, Cheskie Weisz’s CW Realty and Zelig Weiss’ Riverside Developers. Public records show Dushinsky has the most debt on BofI’s books, with more than $80 million spread across three loans.

The model means BofI has little to no interaction with the sponsors themselves. Scott Barone, whose firm Barone Management secured $15.8 million from BofI via Emerald Creek Capital in 2016, said he “never had any actual dealings with them.”

Sources identified Sal Salzillo as one of the main point people leading lender financings on development deals for BofI in New York. However, Salzillo left in March for Sandhills Bank, a South Carolina-based bank owned by the Kalikow real estate family. He could not be reached for comment.

Garrabrants wouldn’t reveal the names of his New York real estate team members and said the firm does not target any specific community for its business.

“There’s no specific marketing or any kind of specific targeting of any particular group of borrowers,” he said.

The wide web

In 2016, the SEC started hitting the bank with subpoenas, after a whistleblower filed a lawsuit in 2015 alleging the bank might have been lending illegally to certain foreign nationals in possible violation of federal money laundering laws. The suit also alleged the bank failed to fully disclose certain loan practices to regulators. The SEC dropped its investigation in June 2017 without taking any legal action. Garrabrants attributed the lawsuit and subsequent inquiries to the machinations of angry short sellers who watched the bank’s stock continue to climb. In a January 2017 earnings call, he called the allegations “fake news.”

But some have questioned whether the SEC dropping its investigation and the bank’s lending to a major Kushner Companies development project is too much of a coincidence. Jared Kushner joined the White House last January as a senior adviser, and although he has resigned from company positions, he still retains ownership in much of the company portfolio. Garrabrants dismissed these questions as part of a “tin-hat conspiracy” and said the SEC cleared the investigation months before it began talks with Fortress — Kushner’s lender at One Journal Square — about acquiring the senior interest in the loan.

Kushner Companies has faced a series of challenges at the project and it appears unlikely that Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop, a Democrat, will grant the company building permits or tax abatements, though he denies it has anything to do with opposition to the Trump administration. Garrabrants was critical of Fulop, but said BofI will make money in the deal regardless. If Kushner Companies can’t build it or if it defaults, someone else will get the project done, he said.

“With respect to any kind of hurdles that arise as a result of any kind of issues related to some of the things that I’m sure people who are motivated in certain in manners put in place,” Garrabrants said in a statement apparently directed at Fulop, “hurdles in respect to [Kushner] in particular, and essentially punish him for his political affiliation, those are more difficult.”

However, he continued, “If we ended up with an ownership interest. … There will be people lining up to make sure that we don’t lose money on that project.”