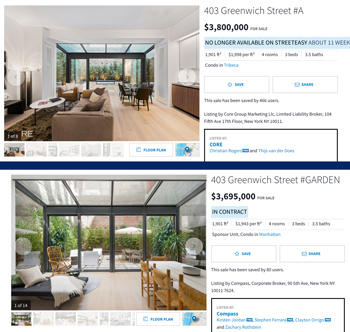

UPDATED, Aug. 16, 12:40 p.m.: In 2011, with the condominium market booming, Greg Altshuler’s Colonnade Group scooped up 403 Greenwich Street with plans to redevelop the former warehouse into high-end condos.

But by the summer of 2017, when the building was complete, the luxury sector was teetering toward a slowdown. In October of that year, Residence A — a three-bedroom pad asking $3.8 million — hit the market. It sat there for the next 235 days.

Then in May, a new listing agent hit reboot: The apartment was re-listed for $3.69 million as the building’s “Garden” apartment and went into contract 18 days later. The lengthy listing history of “Residence A” was still online — if you knew where to find it.

Real estate has never been more transparent — but amid a market slowdown, buyers are acutely aware that some units are sitting on the shelf. And as they pass over anything that’s not “new” to the market, some agents are looking for ways to make their listings seem fresh.

Changing apartment numbers to make a listing appear new is “an old trick,” said Olshan Realty’s Donna Olshan, who tracks the luxury market.

Lately, though, looking new requires some finesse. During the last week of July, Olshan said properties asking $4 million-plus spent an average of 536 days on the market.

That kind of tortured marketing time is giving agents added incentive to circumvent online portals with granular detail about each unit.

Brown Harris Stevens’ Lisa Lippman, for example, has used several iterations to describe one of her listings at 160 West 86th Street.

In January, she listed “Unit 3” for $7.395 million. After cutting the price to $6.9 million in April, Lippman re-named the apartment unit “3A” last month, according to RealPlus.

“When we switched it, people started calling,” said Lippman, who played around with the unit number not just to avoid looking stale. Without a letter after the number three, she said, buyers did not realize the apartment is a full-floor condo.

“Of course it’s somewhat disingenuous, but in the end, I don’t think you’re really fooling anybody,” she said.

Spilling out into public view

Such subtle changes, though, can make it difficult to trace a unit’s listing history.

That’s the case with Unit 41B, a two-bedroom condo at One57 that was first listed for $7.75 million in January 2017. In January of this year, the seller cut the price to $7.495 million, only to pull the listing in April, according to StreetEasy.

Later that month, however, Douglas Elliman’s Janice Chang and Tim Hsu re-listed Unit 41BH for $7.495 million. (Chang and Hsu did not respond to a request for comment.)

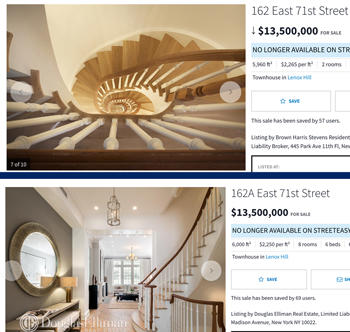

One of the industry’s better-known examples of a renamed listing involves an Upper East Side townhouse that was on and off the market from 2011 to 2015.

For most of that time, Brown Harris Stevens’ Paula Del Nunzio represented the sellers of 162 East 71st Street, who asked between $12.2 million and $14.8 million at various points from 2011 to 2014, according to StreetEasy.

In May 2015, however, the seller swapped Del Nunzio for Elliman’s Fredrik Eklund and John Gomes, who listed 162A East 71st for $13.5 million — effectively erasing the long and winding listing history of No. 162. The property sold for $13 million within three months. Neither Del Nunzio nor Eklund and Gomes responded to a request for comment.

162(A) East 71st Street listings

But those examples are tame compared to the story that’s gripped South Florida real estate circles, where a broker was found guilty in June of extorting rivals Jill Hertzberg and Jill Eber — better known as “The Jills.” Kevin Tomlinson, himself a successful broker, discovered that someone on the Jills’ team had manipulated the local MLS to hide the fact that their listings had been on the market for longer than six months. He demanded $800,000 to keep quiet, but the Jills went to the police and recorded his phone calls. A jury recently found Tomlinson guilty on two felony counts, and he is now awaiting sentencing.

That case, though — coupled with the struggle between brokers and portals to control listings data — has thrust the practice of massaging listing information into the public domain.

Last year in New York, several major brokerage firms became locked in a standoff with StreetEasy after the portal — citing concerns over data accuracy — decided not to accept the Real Estate Board of New York’s newly syndicated listing feed (RLS).

Even unintentional errors are the scourge of third party listing portals like StreetEasy and the REBNY RLS, the latter of which can impose fines on agents caught misleading buyers.

For its part, StreetEasy uses a set of algorithms that scan listing entries and catches anomalies. If the company’s support staff deems something to be inaccurate, the listing can be taken down. “Data integrity and accuracy is of the utmost importance at StreetEasy,” a spokesperson said. “If someone were to flag any information across our site or apps as suspicious, we investigate immediately.”

It’s unclear how many listings in New York City are “gamed,” but a cursory look online confirms that some agents are employing a variety of tactics to manipulate the way listings appear online (even if they’re not deleting or hiding information a la the Jills’ team.)

Take, for example, a Chelsea townhouse that hit the market last year asking $7.85 million.

According to StreetEasy, the property at 332 West 20th Street was listed in February 2017, but was pulled off the market a few days later. In April 2018, the identical house — this time called 344 West 20th — was listed for sale on Leslie J. Garfield’s website. (The unit was marked “in contract” in July.)

At 11 North Moore, a penthouse asking $22.5 million appeared on StreetEasy twice — as PHE and as Unit 9. As of July 26, PHE was under contract while Unit 9 remained an active listing.

Listing agent Tamir Shemesh of Douglas Elliman said he created two separate listings — one depicting the unit configured as a four bedroom and one as a five bedroom — so that buyers could easily navigate online search fields. He said it was an error that only PHE was marked in contract, though he said he would consider leaving Unit 9 marked as an active listing “to make sure we have a back-up” option if the buyer backs out. On Aug. 8, Unit 9 was pulled from StreetEasy and on Aug. 14 PHE was listed as being sold, though the sale has not yet hit city records.

If it’s new to you…

If brokers can make a listing look fresh, many will jump at the chance, and with good reason.

During the second quarter of 2018, the number of sales dropped 24.9 percent year-over-year to 10,819, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel. Meanwhile, inventory was up 6.5 percent (to 19,753 active listings). Compared to this time last year, the absorption rate — how long it would take to sell out all active listings — ballooned 41 percent to 5.5 months.

In the case of 403 Greenwich, listing broker Stephen Ferrara of Compass copped to re-naming the ground-floor unit and said he “firmly” believed it should have been called a garden apartment all along.

403 Greenwich Street listings

“One of the special features of this exceptional apartment is that it has a private garden,” he wrote in an email. “Changing the unit number was a great way for us to reposition the residence.”

Of course, calculated misrepresentations are “completely unacceptable” under both New York state and REBNY rules, said Neil Garfinkel, the association’s general counsel. “Advertising has to be honest and truthful,” he said. “You can’t mislead the consumer.”

It’s less clear who’s to “blame” if there’s a technical (or accidental) reason for a unit change.

CORE’s Adrian Noriega, for example, said he wasn’t responsible for renaming the top unit at 15 West 20 Street as “Penthouse” from “PH10/11.” Instead, he said CORE switched its back-end listings platform this year (swapping out Realplus for Perchwell). With that change, some listings had to be re-entered and did not appear the exact same way.

“It ended up working to our advantage because it showed as a new listing,” said Noriega, who took over the listing from Douglas Elliman in April.

Noriega said he would never have made the change himself, though he also believes that no intelligent person spending more than $5 million is so easily deceived. “You can easily click on a listing and recognize that they’re the same unit,” he said. “You’re not tricking anybody.”

In fact, he intentionally played up how long the penthouse had been on the market to show that the current price of $1,500 a foot is a steal. (And also to show how much the price may appreciate in a few years.) “There’s a lot of potential with this unit,” he said.