As WeWork crumbled last year, one onlooker watched with glee.

Amol Sarva, who as CEO of office-space firm Knotel had needled his high-flying rival for years, finally had his moment. “We’ve been waiting for the music to be over,” Sarva told the Financial Times. “And now the music is over, and it’s time to dance.”

He strutted as WeWork lost $40 billion in value, ousted its CEO, slashed head count by thousands and slowed leasing in a mad scramble to trim losses.

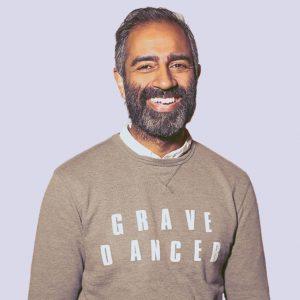

Amol Sarva (Credit: Wikipedia)

But as the dust settles on WeWork’s implosion, Knotel finds itself struggling to convey why its core business — leasing office space and subletting it for more money — is any different. It is similarly unprofitable, and news reports have been spotlighting its vacancy rates, layoffs and decline in leasing activity.

“Knotel is in the WeWork business,” said Ryan Freedman, a general partner at Corigin Ventures, an investor in brokerage Compass and home-entry firm Latch. “It puts them in the crosshairs to get their house in order immediately.”

The media coverage has tainted Knotel’s image as a cash-flush startup reported to have raised $400 million last year. Its August funding round, which was led by a division of Kuwait’s sovereign wealth fund, Wafra, blessed Knotel with a $1.3 billion valuation and the revered “unicorn” label.

In an interview with The Real Deal, Sarva downplayed the metrics. Vacancy rate, for one, is a performance measure used only by the “traditional” real estate industry, he said, adding that Knotel is booking $10 million in new business in New York per month.

“It’s really reading from the old song book,” Sarva said of the criticism. “Flex is about liquidity — you need to have a liquid portfolio to serve these customers. That’s the way to think about it.”

Knotel is in the WeWork business. It puts them in the crosshairs to get their house in order — Ryan Freedman, Corigin Ventures

Some investors are undeterred. Barry Gosin, the CEO of commercial brokerage Newmark Knight Frank, which has invested in Knotel’s last two funding rounds, said the pullback on leasing, for example, showed discipline by the company.

“Knotel is on a good track,” Gosin said. “They have slowed their activity to achieve their goal of profitability.”

Sarva has been trying to bend Knotel’s narrative back to where it was. In a Jan. 27 conference call with reporters he said the company had $350 million in contracted annual revenue and “profitability very much in sight.” But he stopped short of saying when, offering only that it would be “cash-flow break even” by the end of the year.

Skeptics could be forgiven: According to internal figures reported by TRD in 2018, Knotel previously expected to reap $43 million in profit on $198 million in revenue once it leased 2.5 million square feet of “mature” office space — meaning at least 90 percent occupied. Its office portfolio currently spans 5 million square feet; the company declined to say how much space is occupied.

Updating previous disclosures, Sarva said Knotel actually raised $440 million last year: a $190 million equity payment and a $250 million investment by Wafra in a joint venture with Knotel. Sarva declined to say how the latter capital would be used, except to say “flex-office, period.”

Also unclear are any plans for a public offering, which the company would not discuss. It now faces a long year of convincing investors and customers that it is a viable alternative to WeWork. But in another parallel to its better-known competitor, Knotel’s ventures into other business lines — including a blockchain platform and a furniture subscription service — have sputtered.

Sarva appeared to sense that he has some explaining to do. After returning from the World Economic Forum in Davos over the weekend, he promised to convene a gathering to lay out Knotel’s plans for 2020. “I’ll spend some time on Knotel, flexible office, real estate, what happened last year, and what to expect this year,” he wrote in an email to colleagues. “I suspect some press will even have questions for me.”

Unorthodox entrepreneur

Sarva, who previously co-founded Virgin Mobile USA, has tracked a well-worn path from McKinsey consultant to entrepreneur. He holds a doctorate in philosophy from Stanford University, and has launched several startups, including a neuroscience technology company. In 2016, he founded Knotel with Russian-American investor Edward Shenderovich after the pair leased their Manhattan office space to friends.

Known for his eccentric persona, Sarva appeared on Bloomberg TV in a shimmering purple coat covered in dragons. In an 800-word holiday message to colleagues he shared what he called “end of year learnings,” which included “Burning Man is the kindest place on Earth,” and the “Two best things I ever ate were this year in Japan: a tomato with salt and a raw egg (stirred).”

Sarva, 42, has also drawn attention for trolling WeWork. When it jettisoned hundreds of employees early last year, he tweeted, “WeWork layoffs. Sorry folks. We didn’t mean to.” Another time, Knotel accused WeWork of corporate espionage. Later he had a school bus park in front of WeWork’s Chelsea headquarters emblazoned with a message: “Graduate from Co-working,” which Sarva later said was directed at “the bros hanging out doing keg stands at WeWork.”

Until recently, Knotel had sought to beat WeWork at its own game, rapidly signing leases and vacuuming up millions of square feet of office space. In 2018 it said it had more locations than WeWork in New York, even though WeWork had more square feet. And last month, Knotel said it had reached 5 million square feet globally across 17 cities after adding more than 1.1 million square feet in the second half of 2019.

Sarva (left) trolled WeWork by putting this bus in front of his rival’s office (Credit: Twitter.com/Knotel)

“In the three years we’ve been operating we’ve surpassed [WeWork] in the number of buildings [leased in New York]. Same in Paris, same in San Francisco,” Sarva said on Bloomberg TV last year.

Knotel says its build-out costs are substantially lower than WeWork’s and points to a shift toward revenue-sharing partnerships with landlords, as opposed to long-term leases, but these make up only 10 percent of its portfolio. Its competitors, including Convene, Industrious and Regus, are also moving to partnership agreements to avoid the massive lease commitments that obscured WeWork’s path to profitability.

The prime reason Knotel is nothing like WeWork, Sarva says, is that it offers unbranded floor plates to enterprise clients, such as Microsoft and Starbucks. He has claimed that WeWork primarily has office space for freelancers and small startups.

But the distinction has become outdated as WeWork has gravitated toward enterprise clients too. At their core, both companies lease office space and re-lease it at a premium.

The similarities are not lost on Knotel’s employees. “There was a lot of shade thrown on other businesses,” said one who was recently laid off. “But it was the exact same business model.”

Others drew comparisons between the colorful personas of Sarva and WeWork co-founder Adam Neumann, who was pushed out as CEO last fall. Although the pair have wildly different backgrounds — Sarva has a Ph.D., has launched several successful companies and advises many more, while Neumann took 15 years to receive a bachelor’s degree and launched a short-lived startup that sold knee pads for babies — one former employee said the two are alike.

There was a lot of shade thrown on other businesses. But it was the exact same business model — former Knotel employee on the CEO’s criticism of rivals

“[Sarva] hides behind his ability to be eccentric and walks around like everything’s fine,” the former employee said, “when everything’s a disaster.”

Facing Headwinds

The firm is encountering some turbulence. In November, Crain’s reported that almost 800,000 square feet of Knotel’s office space in New York was or would soon be vacant, assuming it didn’t bring in new customers.

Then CBRE released data showing Knotel’s leasing activity in the U.S. had plummeted 80 percent in the final quarter of 2019 from the previous quarter, almost mirroring WeWork’s 93 percent drop after it pulled plans to go public.

Sarva dismissed both of these metrics as dated, adding, “We’re doing really well.” By comparison, Knotel’s competitors’ leasing was holding steady or growing, the CBRE report showed. Industrious, which expects to be profitable in the first half of 2020, recorded a 6 percent decline in leases signed, while Spaces, a co-working subsidiary of Luxembourg-based IWG, saw a nearly 11 percent increase. (The study did not include partnership agreements.)

High vacancy rates are common at flexible-office firms. For the first half of 2019, IWG reported a 30 percent vacancy rate across its global portfolio; WeWork had a 20 percent vacancy rate at the end of the third quarter.

But as Knotel’s growth has slowed, its head of corporate finance departed, and in mid January it laid off two dozen employees, or a third of its staff focused on the New York market. Sarva said that 10 senior employees had been hired since the start of December and that staff costs had not been cut.

“It’s unfortunate that sometimes we have to make the hard decisions to get the results we want,” he said, adding that the company has more than 500 employees.

Some of the former staffers — mostly sales and customer representatives — told TRD that Knotel had gained a reputation for delaying payments to vendors in New York. Sarva did not deny that but said his firm had processed 5,000 vendor payments amounting to “tens of millions” of dollars in the past 30 days.

“Every company I ever ran, I wish I got paid sooner,” Sarva said. “We’re kind of a bigger company now and we need to be careful to get things right.”

Some Knotel customers acknowledge the company’s issues, but say it provides a better product than WeWork. L.D. Salmanson, whose real estate data firm Cherre is located in a Knotel space in Midtown, said the flexible office space model has allowed his business to thrive without the restrictions of a long-term lease.

Every company I ever ran, I wish I got paid sooner — Amol Sarva on Knotel’s late payments to vendors

“I’m tired of this five- to seven-year bullshit,” said Salmanson, referring to the lease commitments that landlords demand.”[Flexible office] is a fucking better product than anything on offer. Is that Knotel yet? No. But they are a lot closer than WeWork.”

False starts

Knotel’s efforts to generate more revenue through new business lines, including a well-publicized foray into blockchain, have borne little fruit.

In 2018, Knotel acquired data firm 42Floors, which it said would be used to build a blockchain product called Baya to aggregate and distribute commercial real estate data. It then partnered with data firm CompStak to strengthen its ties to real estate information.

But the product has suffered from false starts and been met with limited enthusiasm from the real estate industry. During a November 2018 meeting at the Manhattan headquarters of Newmark Knight Frank, Sarva attempted to drum up support for the blockchain product with a group of industry executives. He was accompanied by Patrick Morselli, a former executive of WeWork and Uber, who was to lead the venture.

Those in attendance — including executives of NKF, JLL, a credit-rating agency and real estate data firms Reonomy and CompStak — left the meeting not only noncommittal but bewildered, according to several who attended.

The launch planned for March 2019 never happened, and all that remains of Baya’s website is a page that says: “Coming Soon! Welcome to Baya! We are preparing something amazing for the commercial real estate industry.” CompStak CEO Michael Mandel said in a statement that CompStak is not “actively working with Knotel on Baya,” but that Knotel remains a client.

Sarva insisted that Baya remains an “important initiative” for Knotel and said its team — led by Morselli — reports directly to him. He said Baya has 20 customers committed to a prototype of the product, but declined to divulge them or any information about the product, citing “competitive dynamics that I don’t want to trigger.”

Separately, a subscription service for workplace furniture that Knotel launched last summer, Geometry, was set back when three employees linked to the service were laid off this month.

Sarva declined to say how many employees are working on the business, but said it had sold all of its 2019 product and was now being refocused on enterprise clients instead of small businesses. It is a “very big part of an important buzz for us this year,” the CEO said.

Adults in the room

On Jan. 29, Sarva convened the gathering he had emailed about following Davos, where he had bunked with Tim Wu, the Columbia Law professor and coiner of the phrase “net neutrality.” Wu sat beside Sarva at the meeting, held at Knotel’s first location, on West 17th Street in Manhattan.

Gone was the dragon jacket. Wearing blue pants and a neat pair of yellow loafers with tassels, Sarva told the crowd of several dozen that Knotel planned to spend this year being “open and accountable.”

“Last year was an insanely great year for us — we started as a minion and all of a sudden we are kind of a big deal,” Sarva said. “It feels more and more like all eyes are on us as others have exited the field. And we are going to try and take responsibility for that.”

As for WeWork, this time Sarva did not mention it — by name, anyway.

“A lot of folks in startup-land have been running their businesses in relatively irresponsible and foolish ways,” he said. “We thought we were doing it right the whole time.”

Contact David Jeans at dj@therealdeal.com