Every day that the city is more or less shut down, is another day of bills piling up for John Moloney.

Moloney, who already owns two pubs in Manhattan — titled John Doe and The Junction — and a third in Queens — Austin Public — was planning a grande opening for a fourth when Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that all eateries must shut their doors for the unforeseeable future.

Restaurateurs operating the nearly 27,000 food and beverage establishments across the city scurried to restructure their business models for takeout. But for bar owners like Moloney it’s a logistical nightmare, and there’s no way the business generated would be enough to cover his rent.

“I’m under no illusions about rent, you know. I signed a contract. I’m a big boy and I understand that I am responsible for this rent,” Moloney said. “But I didn’t sign up for this.”

The mayor goes on TV and says, ‘We’re all in this together.’ I don’t see we’re all in this together at all.

That was three months ago. Today, with Phase II beginning this week, many restaurant owners and landlords are confronting the ugly truth: No one has the money to pay the bills, and no one knows how to make it work.

Nearly 90 percent of 483 businesses in the hospitality industry could not pay their May rent, or only paid a portion of it, according to a survey by the NYC Hospitality Alliance. Looking forward, nearly four percent of respondents said that they will have to permanently close as a result of the pandemic. Another 53 percent said they were unsure of what the future may hold.

Other projections are even more grim. In a study of publicly traded restaurant companies, Aaron Allen & Associates found that six of every 10 restaurant chains are at risk for bankruptcy, with small companies facing a larger probability of disaster.

“Once a few landlords crack down, it’s really going to be Armageddon,” said Aaron Allen, the founder of the global restaurant consulting firm. “What’s currently happening is armies are being created to renegotiate leases.”

Allen expects the situation to worsen the longer restaurants are forced to operate at partial capacity, with restaurants located in previously popular areas of New York being most affected as commuters and tourists avoid the city.

James Famularo, Meridian Capital Group

“I wouldn’t wish for this in a million years,” said James Famularo, a retail broker with Meridian Capital Group. “Every day I get flooded with bankruptcies and closures.”

It’s gotten so bad that Meridian plans on doubling its number of retail brokers to prepare for a potential wave of vacancies, Famularo said.

Moloney dreads that he may soon become one of those victims. Two of his landlords have allowed him to defer his payments, but another is demanding the keys if he can’t make the $26,000 in rent.

“The mayor goes on TV and says ‘We’re all in this together.’ I don’t see we’re all in this together at all,” Moloney said.

Surviving on crumbs

Even before the pandemic, restaurants were low-margin businesses with a high failure rate.

In New York, I know some folks who sign leases budgeting for 10 percent of their revenues as rents, which means their profits are really, really narrow at that point.

Seventeen percent of independently owned full-service restaurant startups fail in their first year, with the median lifespan of a restaurant being just under five years, according to a 2014 analysis of 81,000 restaurants across the U.S. The figure is likely even higher in New York, where competition is fierce and mom-and-pop shops have fewer resources than the chains.

Rent is one of the largest fixed costs for restaurants, especially in Manhattan and Brooklyn, where asking prices average at $120 per square foot, according to a 2016 New York Times analysis.

“In a lot of other cities, most folks can find places where the rent is about five percent of their sales. In New York, I know some folks who sign leases budgeting for 10 percent of their revenues as rents, which means their profits are really, really narrow at that point,” said Jasmine Moy, whose boutique law firm primarily represents restaurant owners.

To survive, many chefs and restaurant owners in the city have had to renegotiate terms with their landlords.

Andrew Moger, BCD Development

“There was definitely some conflict and combativeness early on, but I think for the most part, there was sort of a general consensus that none of us know what’s happening. Let’s take a breath,” said Andrew Moger, the CEO of BCD Development, a restaurant-focused real estate brokerage and advisory firm. “Now, there is definitely a willingness to have those conversations.”

Moger, whose clients include Chop’t and Dos Toros Taqueria, said that restaurants that previously relied heavily on take-out are more likely to thrive in today’s environment, with a few eyeing expansion. The businesses that are structured around table service are the ones predominantly looking for rent concessions.

For restaurant tenants, Slate Property Group principal Martin Nussbaum prefers structuring the lease as a base rent with a form of percentage rent on top. The base rent may increase over time as restaurants reopen and business returns to normal, he said.

“As an owner of a building I’m very sympathetic to their problems,” Nussbaum said. “If my entire business shut down, I also would be having a hard time and we want to be respectful of that.”

Receiving a base income allows landlords to speak more openly with their lenders about the financial situation.

“We’ve had conversations with all of our lenders and almost all of them know where we are and are acting as a good partner to help solve the problems,” Nussbaum said.

The Gotham West Market in Hell’s Kitchen

For the Gotham Organization, which owns two food halls in Manhattan and Brooklyn, payments from their tenants have been mainly about keeping the lights on in their Hell’s Kitchen location.

Restaurant owners pay for operating costs, such as utilities and supplies, with assistance from Gotham. If necessary, they may defer payments.

“We said that we’d be willing to take a loss for a period of time, if it meant keeping these restaurants open long-term,” Gotham COO Phil Lavoie said. “We decided to take a straightforward approach and everybody’s just paying their share.”

In part, Gotham decided to do so to avoid reopening costs, which restaurant owners feared, in addition to a lack of revenue, would cause them to close permanently.

Lavoie said that his investors have been equally understanding.

“They’re aware of what’s going on. Everybody understands the added value our food halls have,” Lavoie said. “We want to do what we can to keep the restaurants open.”

I’ll see you in court

Not all landlords have been keen to renegotiate. Revenue streams drying up while their mortgage bills await them have left some with only one place to turn to: court.

A few landlords have already filed lawsuits against their tenants, asking for rent payments that were missed as a result of the pandemic.

Though none of her clients have yet been served lawsuits by their landlords, Moy expects they will.

“In a lot of cases right now, landlords are still hoping that people are going to get loan money. They’re still hoping to work out a deal. They’re still hoping the rent will get paid,” the attorney said. “But I do think if the conversation starts to evolve, and if they start to feel like they’re not going to work out a deal, those default notices will start coming.”

Philippe Chow at 355 West 16th Street

In one lawsuit, brought by Philippe Chow, a restaurant serving what it describes as “sophisticated Beijing style cuisine,” the tables have been turned.

The restaurant is arguing that, because the space is unusable, rent is not owed both under the casualty clause of the lease and because the purpose of the lease has been frustrated. Additionally, it is alleging that the landlord, an entity controlled by the Dream Hotel Group, has by asking for rent engaged in tenant harassment — a restaurant protection that the city has provided during the pandemic.

As a result Philippe Chow is asking for a rent credit for the payments made during the time that the restaurant was closed.

Glenn Wright, the founder of Wright Law Firm, said that more landlords are wary to collect rent or negotiate with tenants because they fear being fined for tenant harassment.

“I’ve been going in a lot more to negotiate on behalf of my clients,” Wright said. “Sometimes that’s better and sometimes that’s worse, but I don’t blame a landlord for having this chilling effect, that he would be afraid to speak to his tenant and then be alleged to have been harassing tenants.”

An uncertain future as the city reopens

New York City’s Phase II is expected to herald the reopening of 5,000 eateries across the city by allowing them to spill onto sidewalks and unused parking spots.

My concern is that some restaurants may immediately open, but then what’s going to happen in six months? 12 months? 18 months?

It will help, but restaurateurs worry that the proposal, like other relief bills, will not be enough for them to make rent.

Previous assistance by the city includes caps on delivery fees by third-party services like GrubHub, eviction moratoriums and the suspension of the enforcement of personal liability provisions, all of which may save a restaurant right now, but does little to make up for the backlog of rent.

Restaurateurs are similarly wary of taking advantage of the Paycheck Protection Program, which is not enough to compete with unemployment benefits and allows only 25 percent of the loan to pay for rent and utilities.

Nathan’s Famous restaurant in Coney Island (Getty)

“My concern is that some restaurants may immediately open, but then what’s going to happen in six months? Twelve months? Eighteen months?” said Andrew Rigie, the executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance. “There’s not one silver bullet, but it’s going to be a combination of many different policies.”

In Cincinnati, where outdoor dining began in May, restaurants set up between two and eight tables in spaces allocated to them.

However, 3CDC, the development company that works with 75 retailers and restaurants in the area, had to do a lot more to ensure that stores and eateries would be able to stay in business.

For retail and service establishments, the company provided complete rent relief. For restaurants and bars, which already had their leases structured around percentage rent, 3CDC waived the base rent and collected only a percentage of revenue made through takeout, outdoor dining and, eventually, partial-capacity indoor dining.

“I think [restaurants] have been very creative in the ways that they’ve gone about keeping things afloat,” said Joe Rudemiller, the vice president of marketing and communications for 3CDC. “This is one more way that we can try to help them get through this difficult time while we still do have the limited capacity.”

For New York, indoor dining will only be available in stage three of reopening. Even then, capacity will likely be limited.

Neir’s Tavern, which opened in 1829, was on track to close its doors earlier in the year after a new landlord bought the building and raised its rent three-fold.

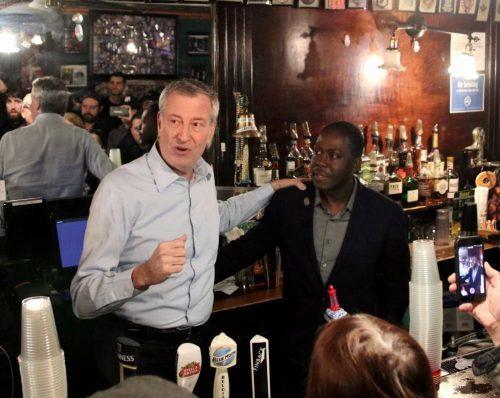

Bill de Blasio at Neir’s Tavern at 87-48 78th Street in Woodhaven

What followed was a media frenzy and campaigns to save one of the oldest bars in New York, during which de Blasio denounced “greedy landlords,” offered a $90,000 grant from the city and struck a handshake deal to renegotiate the lease with the landlord.

However, when Covid-19 hit, the only relief the landlord could provide was 50 percent off the May rent. In June, full rent was once again due.

For Neir’s Tavern to survive, owner Loycent Gordon calculates that it would need 50 percent capacity for indoor seating, outdoor dining, a 25 percent drop in rent and for delivery app charges to remain capped.

“We cannot wait for or hope that indoor dining will come back like it was,” Gordon said. “That is what my strategy is. It’s not to depend on indoor dining for my sustainability, it is to try to ensure that takeout and delivery and outdoor dining, as best as we can do, is sustainable for us.”

Dos Toros restaurant (Getty)

In all, Gordon said that if Neir’s Tavern can get back to 60 percent of revenue fairly quickly, it will be able to start paying its debts and stay in business.

Moloney similarly estimates that, to return to stability, his pubs will have to reopen at 75 percent capacity. But even if the city allows such capacity, it may be difficult to persuade his customers to return.

“People want to go out and meet other people. Guys want to meet girls. Girls want to meet guys,” Moloney said. “Will people go back out is another issue.”