When Fifth Wall Ventures decided to jump into the SPAC market in January, it targeted a raise of $250 million to take a startup public.

Within three weeks, it upsized the offering — twice — before the new blank-check firm closed its $345 million IPO on Feb. 9. “There was a lot of public demand,” a euphoric-looking Brendan Wallace, the venture firm’s co-founder, said during a video call after the IPO.

Wallace said his “lightbulb moment” was in September when he watched one of his portfolio companies, instant-homebuying startup Opendoor, strike a $4.7 billion deal to go public with a blank-check firm backed by Chamath Palihapitiya. The iBuyer went public on Dec. 21 and now has a market cap of $18.2 billion.

“It was, ‘Wow, this is a validation of this instrument and what’s possible here,’” Wallace said.

It’s been about a year since the frenzy around special purpose acquisition companies began, kicked off by big Wall Street names such as Bill Ackman and Palihapitiya. Real estate players and investors have embraced the trend with gusto, taking proptech companies public and raising large sums for future deals. More than a dozen proptech-focused SPACs, backed by names such as Tishman Speyer, CBRE, Cantor Fitzgerald and the Chera family’s Crown Acquisitions, are hunting for deals. This month, real estate investor Scott Seligman, a minority owner of the San Francisco Giants, teamed up with Foxhall Partners’ Brian Friedman and Citigroup alum Ben Friedman to raise a $175 million SPAC. Scott Rechler’s RXR Realty filed papers to raise $250 million for a proptech-focused SPAC. And some, like Zillow co-founder Spencer Rascoff, are on their second SPAC.

“It’s not really a fad,” Cantor CEO Howard Lutnick told CNBC in December. “It is a really good way for fast-growing, high-tech companies to go public.”

So far, SPACs have taken startups like Opendoor and home-services firm

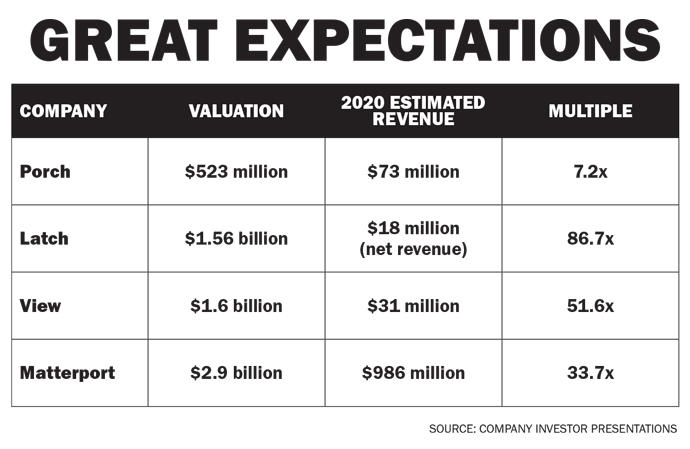

Porch.com public. View (smart glass), Latch (smart locks), Matterport (3D software for virtual property tours) and Hippo (insurance) are slated to go next. Even WeWork — yes, WeWork — may be waiting in the wings. Last year, 248 blank-check firms went public, raising $83 billion — a 510 percent jump from 2019. (As of Feb. 10, 134 SPACs had gone public so far this year, raising $40.4 billion, according to SPACInsider.)

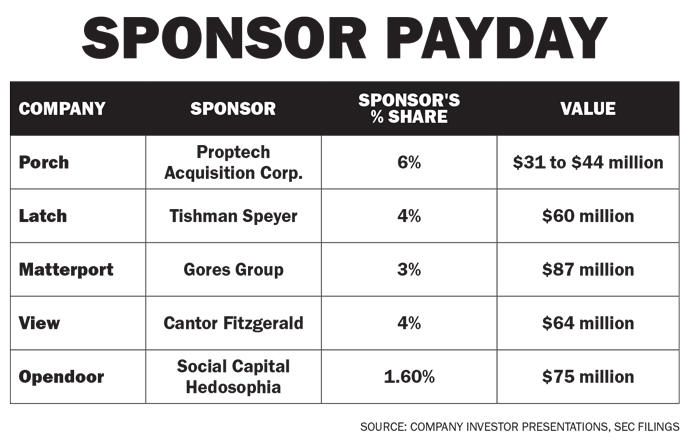

SPACs allow many parties to wet their beaks. Sponsors typically get 20 percent of the company in exchange for putting up a fraction of the funding. Investors get all their money back if no deal is made within two years, or if they opt out. For startups strapped for cash and time, it’s a fast, guaranteed IPO that doesn’t pose the risk of leaving money on the table.

But that quick-and-dirty route to going public has fewer regulatory safeguards than a traditional IPO. Instead of having a quiet period, companies are free to drum up publicity and use projected financials to tell a much rosier story, which can be risky for investors. Latch, for example, projected $167 million in booked revenue in 2020, which represents signed contracts with clients. Its earned revenue for the year was an estimated $18 million.

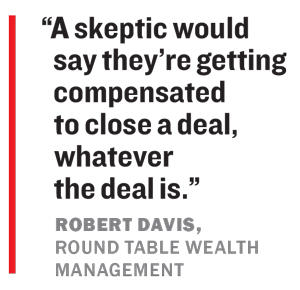

SPAC deals are also negotiated behind closed doors, without the chance for public scrutiny of the company’s inner workings. The SPAC sponsor gets a payday as long as it acquires a target company, even if that company flounders after the merger, a quirk that Dealbook columnist Andrew Ross Sorkin described as “pay before performance.”

Robert Davis, chief investment officer at Round Table Wealth Management, said the guaranteed payday upon acquisition is a “good incentive to get something done.”

But, he added, “a skeptic would say they’re getting compensated to close a deal, whatever the deal is.”

A better IPO

Popular in the 1980s, SPACs gained a reputation for being risky bets and disappeared during the financial crisis. Their resurgence now is part of a growing acknowledgment that the traditional IPO is broken.

This past fall, Rascoff said Zillow’s 2011 IPO, when the company’s stock price shot up 200 percent within minutes, was a “facepalm moment.”

“I was bothered by that spike for years to come,” he tweeted in October, the same month he launched a $350 million blank-check firm of his own. (Too big a stock “pop” essentially means bankers underpriced the deal.) This month, Rascoff backed a second SPAC that’s seeking $250 million.

Wallace pointed to the growing number of high-quality real estate targets as a sign of the evolution of proptech. “Many real estate tech businesses have matured,” he said. “They’re at this inflection point, evaluating whether to stay private or go public.”

Read more

And in a sluggish real estate market, proptech’s ability to help landlords and developers slash costs has become a big selling point.

“Top-line [real estate] revenue has not been going up,” said Ben Friedman, a former trader who partnered with Seligman on BOA Acquisition Corporation to take a proptech company public. “If you think about where you can cut the fat out, a lot of this has to do with technical innovation and using third-party service providers.”

For certain companies that are banking almost entirely on future upside rather than past performance, SPACs may be the only short-term route to public capital. That’s because target companies can share projected earnings, not just historical results.

View, which has raised $1.8 billion from investors, including over $1.1 billion from SoftBank, was not a traditional IPO candidate, admitted CEO Rao Mulpuri. The San Francisco startup, which holds 1,050 patents, has spent $1 billion on research and development since 2007. Its projected revenue for this year is just $75 million, up from last year’s $31 million.

“We don’t have the scale, predictability or profitability to IPO yet, certainly by classic standards,” Mulpuri said. “But we have a demonstrable need for the capital to create further shareholder value.”

Latch raised a $100 million Series B in August 2019, and lost an estimated $61 million on an EBITDA basis in 2020. It is now going public in a $1.56 billion merger with Tishman Speyer. Without a SPAC deal on the table, “there would be no expectation of them going public soon,” said Bradley Tusk, co-founder of Tusk Ventures, which invested in Latch and also has a separate $300 million hospitality-focused SPAC .

Tusk said the marriage between a proptech startup and a top owner-operator — Tishman Speyer controls 78 million square feet of real estate in the U.S. — was part of what investors found appealing.

Tusk said the marriage between a proptech startup and a top owner-operator — Tishman Speyer controls 78 million square feet of real estate in the U.S. — was part of what investors found appealing.

“Some of it is the belief that, ‘Look, what we bring to the table and what they bring to the table is so compelling, we can drive more value,’” said Tusk. Latch has forecast $600 million in revenue by 2024, when it projected it will turn profitable with $3 million in EBITDA.

For Porch.com, a Seattle startup that provides software to home-services companies, its SPAC merger wiped out a history of losses and set the stage for massive growth. Porch’s deal with Proptech Acquisitions Corporation, founded by Abu Dhabi Investment Authority alums Tom Hennessy and Joe Beck, gave it $200 million in cash and left it debt-free.

Without that lifeline, Porch’s accountants raised “substantial doubt” about its ability to stay in business.

“It gives us a significant war chest, which we can use to play offense,” Porch CEO Matt Ehrlichman told TRD in October. “The whole point in taking the company public through a SPAC versus going through a traditional IPO a year later is to be able to capitalize the business as well as we are, faster, so that we can go and be aggressive and take advantage of the M&A opportunities.”

Porch projects $120 million in revenue this year, up from $77.6 million last year. It claims it became profitable in June 2020 with $7 million in EBITDA.

By contrast, Latch CEO Luke Schoenfelder said the startup had “a lot of capital around the table” when it received more than a dozen SPAC offers over the past year. Its options included raising more private capital or going public in a traditional IPO down the road.

“We have a fiduciary responsibility [to investors] to make sure we deliver the best possible outcome,” Schoenfelder said. “The ability to say, ‘Let’s put nearly $500 million on the balance sheet to develop new products,’ it’s pretty exciting.”

But though Schoenfelder may have to answer to Latch’s investors, the SPAC’s sponsor will not. SPAC sponsors do not have a fiduciary duty to the investors in the acquired company.

Relevant experience

Real estate players have slid comfortably into the role of SPAC sponsor. It takes a similar skill set to property investing: Raise capital, find an asset to buy, come to terms and, hopefully, turn a profit.

“My strongest skill set has always been around acquisitions,” said Ophir Sternberg of Lionheart Capital, the developer behind the Ritz-Carlton in Miami Beach. “My business involves buying the right type of property at the right price and structuring the deal well.”

(Sternberg’s OPES Acquisition Corporation struck a deal to take the burger chain BurgerFi public in July 2020. A second, $200 million blank-check firm is focused on proptech.)

Tishman Speyer has backed a dozen proptech startups, including VTS, Openspace and Agora. In January, a Tishman-backed SPAC struck a deal to merge with Latch. Less than 24 hours later, the landlord launched a second blank-check firm, targeting a $250 million investment in a proptech firm.

“Our customers are demanding more and better. They want new technologies to make their lives easier and seamless,” Rob Speyer, Tishman’s chief executive, said in a January interview with TRD. Speyer joined Latch’s board to help the company expand into Europe and the commercial office market. In the Tishman-Latch deal, the landlord will receive a 4 percent stake worth about $60 million, according to Latch’s investor presentation.

According to Evan Hudson, a real estate partner at Stroock, SPACs are also becoming an investment vehicle for many of his clients, including REITs, that previously invested in blind pools.

“Having assets under management is the lifeblood of real estate,” he said. “And capital is what drives returns.”

Perfectly legal

To some, the sheer volume of new SPACs is a sign of a bubble.

With so much capital being raised, there are bound to be blow-ups. A growing number of skeptics worry the number of blank-check firms outweighs targets — which could drive up valuations as sponsors compete for deals.

“The getting is so good right now that people are jumping in with reckless abandon,” said Dave Eisenberg, a co-founder at Zigg Capital who sold his 3D mapping startup, Floored, to CBRE in 2017. “The dynamic now is there’s a lot of people who see a lot of easy money to be made.”

Others point to what they believe is a fundamental misalignment between SPACs and the target companies.

SPAC investors, who usually have no interest in the underlying business, often cash out before the merger is complete, or right after. “We don’t want to own the risk of the operating company,” said Patrick Galley, CEO of RiverNorth Capital Management. By the same token, he said, “If you’re a fundamental investor, why would you want to own a portfolio of cash when you don’t know what it’s going to be?”

In recent months, high trading volume sounded alarm bells for veteran investors. “It’s a perfectly legal regulatory arbitrage,” Joseph Grundfest, a former SEC commissioner, told the Wall Street Journal in November.

New research also paints a sobering picture of SPAC deals a few months after the giddy headlines have died down.

SPAC mergers completed between January 2019 and June 2020 lost, on average, 12 percent of their value within six months, according to researchers at Stanford and New York University. By comparison, the Nasdaq rose 30 percent during the same time.

Proptech-focused SPACs also show mixed results. As of Feb. 5, Opendoor’s stock had slipped 9.8 percent from Dec. 21, 2020, when it went public. Porch Group was up 33 percent from its IPO on Christmas Eve. And United Wholesale Mortgage, which completed a SPAC deal in January, was down 11.9 percent.

To some, those slides warrant greater scrutiny of company valuations.

As with venture capital, investors are underwriting a company’s growth prospects. “You’re turning the pixie dust back into gold,” said Tusk.

Sometimes, there’s a good reason.

“A regular IPO is all about history, you know, protecting the investor,” Lutnick said on CNBC after his CF Acquisitions struck a deal to merge with View. “A company like View needs to talk about its projections … Its margins are 60 percent on this glass.”

Among proptech deals, valuation has been all over the place. View was valued at $1.6 billion, or 21.3 times its projected revenue of $75 million this year, while Opendoor was valued at $4.7 billion, on par with its 2019 revenue. Latch’s $1.56 billion deal was 9.3 times its estimated booked revenue of $167 million in 2020, but 86.7 times its estimated net revenue of $18 million.

Schoenfelder drew a parallel to real estate, where developers pencil out projects based on projections. “How many buildings are built on historical financials?” he said. Latch’s customers operate in the same way, placing orders far in advance in multiyear projects. “When you build infrastructure, you have to plan ahead,” he said.

But Fifth Wall’s Wallace said valuations are also a function of the market opportunity that exists today.

Real estate represents 13 percent of the U.S. economy, but the sector spends just half of 1 percent on IT, he said. For that reason, category-leading companies can command a valuation that reflects big growth potential.

“The commensurate opportunities are so vast that it is possible to pursue valuations that might optically seem very high,” he said, “and have them be totally justified.”

He predicted a two-track fate for SPACs.

“It’s kind of a flat-footed resolution of what’s happening in the SPAC market to say it’s a bubble,” he said. “I don’t think it’s a bubble for the highest-quality sponsors and businesses.”

Even Palihapitiya, who’s become the unofficial face of SPACs and described Opendoor as his “next 10x idea,” cautioned prudence.

“SPACs may be easy to raise … but they are hard to execute and success isn’t guaranteed,” he tweeted Feb. 3. “Good luck to all the players.