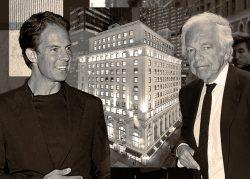

When fast-fashion chain Mango agreed to sublease Ralph Lauren’s 28,000-square-foot Fifth Avenue store last November, the deal seemed like a win-win for both retailers.

Mango would be able to explore the idea of having a store on one of the city’s most iconic shopping corridors, at a fraction of the cost. Ralph Lauren, meanwhile, was struggling due to the pandemic, and would have a chunk of its rent paid off.

But the deal hasn’t worked out quite as either hoped — and shows some of the challenges inherent in retail subleasing, which experts believe could become more popular as tenants struggle to make rent and landlords look for options.

Subleasing has become increasingly prominent in the office sector throughout the pandemic as companies reassess their workforce needs. Major companies like JP Morgan Chase and PricewaterhouseCoopers are among the firms testing the subleasing waters, and available office space hit record highs at the beginning of the year.

Retail subleases aren’t quite there yet, but lawyers and brokers who work with retailers have seen an increase in deals being made. With the pandemic-fueled reckoning that brick-and-mortar stores are experiencing, that number may grow.

Read more

“Tenants are going to get anxious to cut ties and resolve issues so they can budget appropriately going forward. Landlords are going to get frustrated worrying about whether they’re going into default on their loans,” said attorney Laura Brandt, who brands herself as the Retail Lawyer. “So I think more deals are going to get cut down the line.”

Digitally native brands and up-and-coming companies have taken advantage. Similar to pop-up retail spaces, subleasing deals allow younger brands to explore having a brick-and-mortar business without the commitment of a long-term lease or having to build out a storefront.

“Most of them are less than five years old. So to ask one of them to sign a 10-year lease, sometimes they say to themselves, ‘Wait a minute, why would I do that if my company is not even that old? Who the hell knows where I’m going to be in another 10 months, let alone 10 years?’” said Brandon Singer, CEO of brokerage Retail by MONA, which has orchestrated subleases for companies like BooHoo, Showfields and Happy Returns.

Landlords may also become more willing to accommodate subleases in the face of plunging rents and rising retail vacancies. Last fall, 17 of Manhattan’s biggest retail corridors saw their average asking rents drop from the same time last year, with those decreases ranging from 1 to 25 percent, according to a report by the Real Estate Board of New York.

On Fifth Avenue, the average asking rent hit $271 per square foot, a 22 percent year-over-year decline.

And a recent survey by The Real Deal found that 30 stores along Fifth Avenue’s most prominent section — from 42nd to 59th streets — were vacant.

“An office building with a vacant retail space, it’s almost having a beautiful smile with a missing tooth,” said Matthew Chmielecki, CBRE senior vice president with the New York Tri-State Region Retail Services Group, who has worked on subleasing agreements in the past.

Still, those vacancies could also stand in the way of more sublease deals being made.

“Landlords have the ability to be more flexible than a tenant who is looking to sublease their space,” said JP Sutro, the executive managing director of Lee & Associates’ New York City office.

For example, landlords can offer shorter leases with the option to extend, along with other benefits that tenants who are offering subleases have no control over.

And there are downsides to retail subleases — namely, a landlord getting involved and potentially scuttling the deal, which is what happened with Mango and Ralph Lauren.

The deal between the two retailers would have seen Mango paying just $5 million per year to lease Ralph Lauren’s storefront at 711 Fifth Avenue — a discount of more than 20 percent from the luxury brand’s $27 million annual rent. But the landlords — New York-based real estate investment firm Shvo Group, Bilgili Group, Deutsche Finance and the German pension fund BVK — rejected the sublease on the grounds that Mango doesn’t meet the caliber of luxury tenant they envision for the property.

Ralph Lauren is now in arbitration over the scuttled deal, according to Business Insider.

“Landlords keep tight control,” said Brandt. “They’re protecting their investment. These properties are their business. So they need to make sure that they’re getting the right kind of tenant that’s going to stay in business and continue to pay rent.”

Though Chmielecki declined to comment on any specific cases, he added that “Landlords, rightfully so, view their retail as the front door to the building.”

“For better or for worse, the landlords are much more selective over who’s right next to their lobby than who’s on the 14th floor of their building,” he said.