“Not refinanceable” is the way Vornado Realty Trust described the retail portion of the St. Regis Hotel earlier this year after the REIT defaulted on the property’s $450 million loan.

The company’s lender, Crédit Agricole, surely didn’t like the sound of that. Last week the French bank granted Vornado and its partners a five-year extension on the loan in exchange for paying down a significant portion of the principal.

It’s the latest big-ticket property to get a second life on its mortgage as borrowers and lenders come up against commercial real estate’s $1.5 trillion wall of maturities.

For the banks and CMBS special servicers overseeing these loans, they get to avoid the messy tangle of foreclosing on properties. The building owners get to live and fight another day but at a cost, as they’re at the mercy of their lenders.

“This is not an easy situation for anybody” said Michael Cohen, head of the CMBS advisory firm Brighton Capital Advisors.

For owners who want an extension on their due date, the cost is high, according to Cohen.

“They’re going to take a bath,” he said.

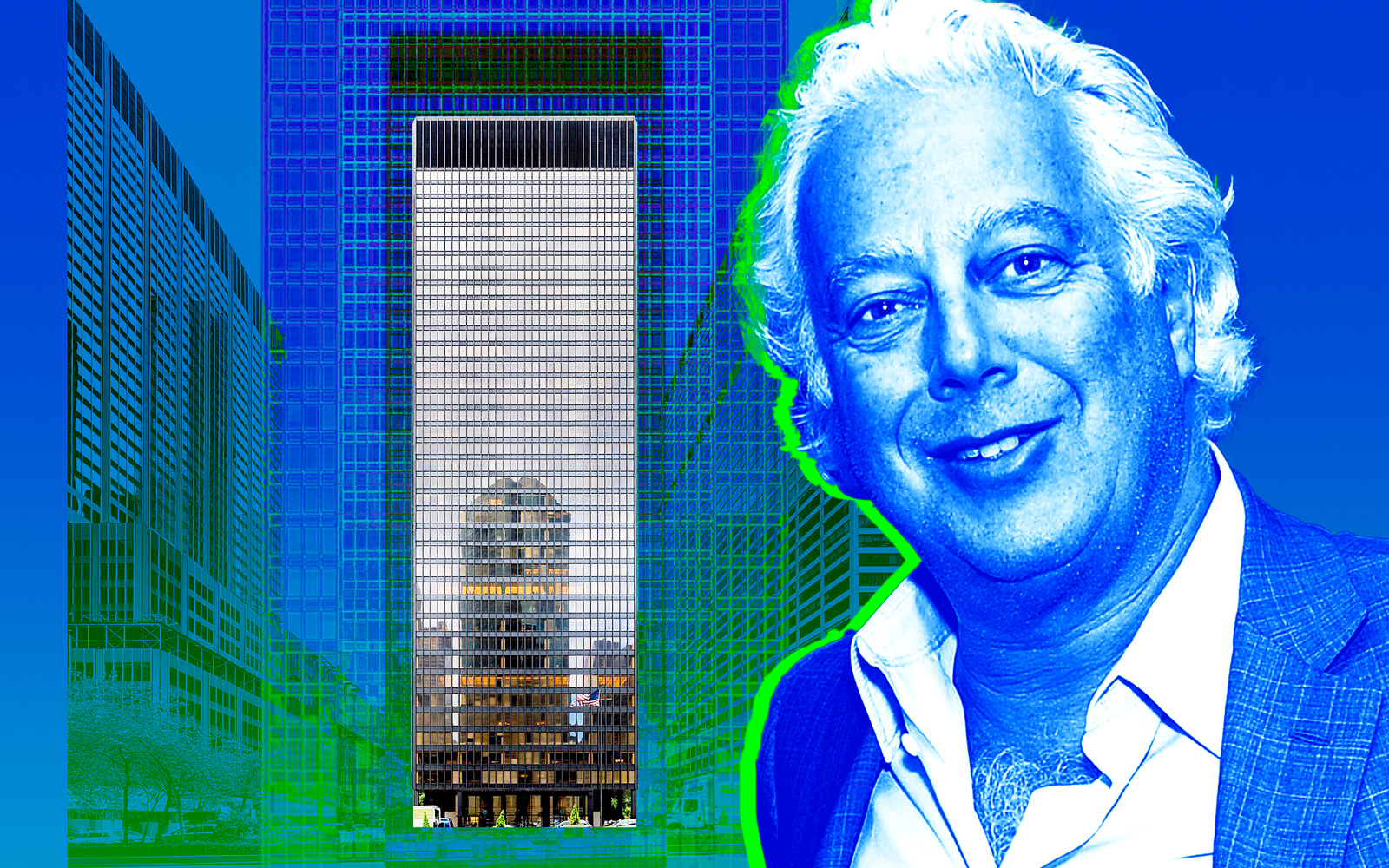

Earlier this year, Aby Rosen’s RFR got an extension on its $1 billion mortgage at the Seagram Building at 375 Park Avenue after Rosen went to the market to try and refinance the loan. GFP Real Estate got more time on its $120 million loan at the 42-story DuMont Building at 515 Madison Avenue. And Tishman Speyer earlier this month extended its $485 million mortgage for its office building at 300 Park Avenue.

While some lenders are looking to tear off the Band-Aid and take back properties as soon as they can, others see a light at the end of the tunnel. In their best-case scenarios, borrowers can get a handle on their debts and will face a better refinancing market when the new term is up.

But an alternate scenario is that the office market gets even worse, and banks begin taking back those same properties a few years from now.

“The lender’s only upside is to get paid back,” Cohen said.

What’s the ante?

Efforts to prolong repayment calls to mind the “extend and pretend” deals that received so much criticism in the wake of the financial crisis, when many lenders were accused of kicking the can down the road to avoid writing down the values of their loans.

But since many of the borrowers getting extensions now are writing checks to reduce principals or top off reserves, today’s deals feel more like restructurings.

In the case of the St. Regis retail, which Vornado owns with Crown Acquisitions and the Qatar Investment Authority, the borrowers agreed to write a check for $95 million to reduce the balance to $355 million. The partners had defaulted on the loan late last year.

At the Seagram Building, the special servicer on the CMBS loan collected $15 million toward the principal, and RFR agreed to pay down another $40 million over the next two years.

Tishman Speyer and its partner at 300 Park Avenue, South Korea’s National Pension Service, agreed to put more than $30 million into a reserve fund to cover expenses like leasing costs, according to a source familiar with the deal.

And at 515 Madison Avenue, GFP paid $5 million down on the loan and agreed to contribute significant equity to reserve funds for tenant improvements and leasing commissions to fill the building’s empty space, notes from the special servicer show.

While Vornado’s loan was issued by a bank, the three others are CMBS deals, which are usually more difficult to modify due to the strict rules around the securitized loans.

GFP’s Jeff Gural said he didn’t even try to refinance the 515 Madison loan, knowing that they wouldn’t be able to do so at this time. He said it took some time to get in touch with the special servicer, but when he did negotiations went pretty smoothly.

“The number one criteria for them was to put up money,” he said.

Read more

The roughly 330,000-square-foot building is 83 percent occupied, but that number is expected to drop to 77 percent this year as tenants move out, according to the special servicer notes.

Gural believes he can improve the building’s performance by the time he needs to refinance the loan.

“My guess is that when the loan comes due we’ll only owe $85 million and hopefully have a full building and interest rates will be lower,” he said.