Rental projects often hit a wall in the City Council for not offering enough affordability. In the case of the Community Builders’ 106-unit proposal for Far Rockaway, the opposite happened.

The nonprofit tried to run its 100 percent affordable project through the city’s political gauntlet, only to meet stiff resistance from the local community board and, more importantly, the local City Council member, who had the power to block the needed rezoning.

Facing a deadline to get its application for 29-32 Beach Channel Drive through, Community Builders attempted an unusual and speedy pivot, converting its project into an 89-unit co-op that promised to bring homeowners rather than low-income tenants.

After some frantic phone calls, quick thinking and a hand from the Adams administration and Queens Borough President Donovan Richards, the developer won Council approval Aug. 3.

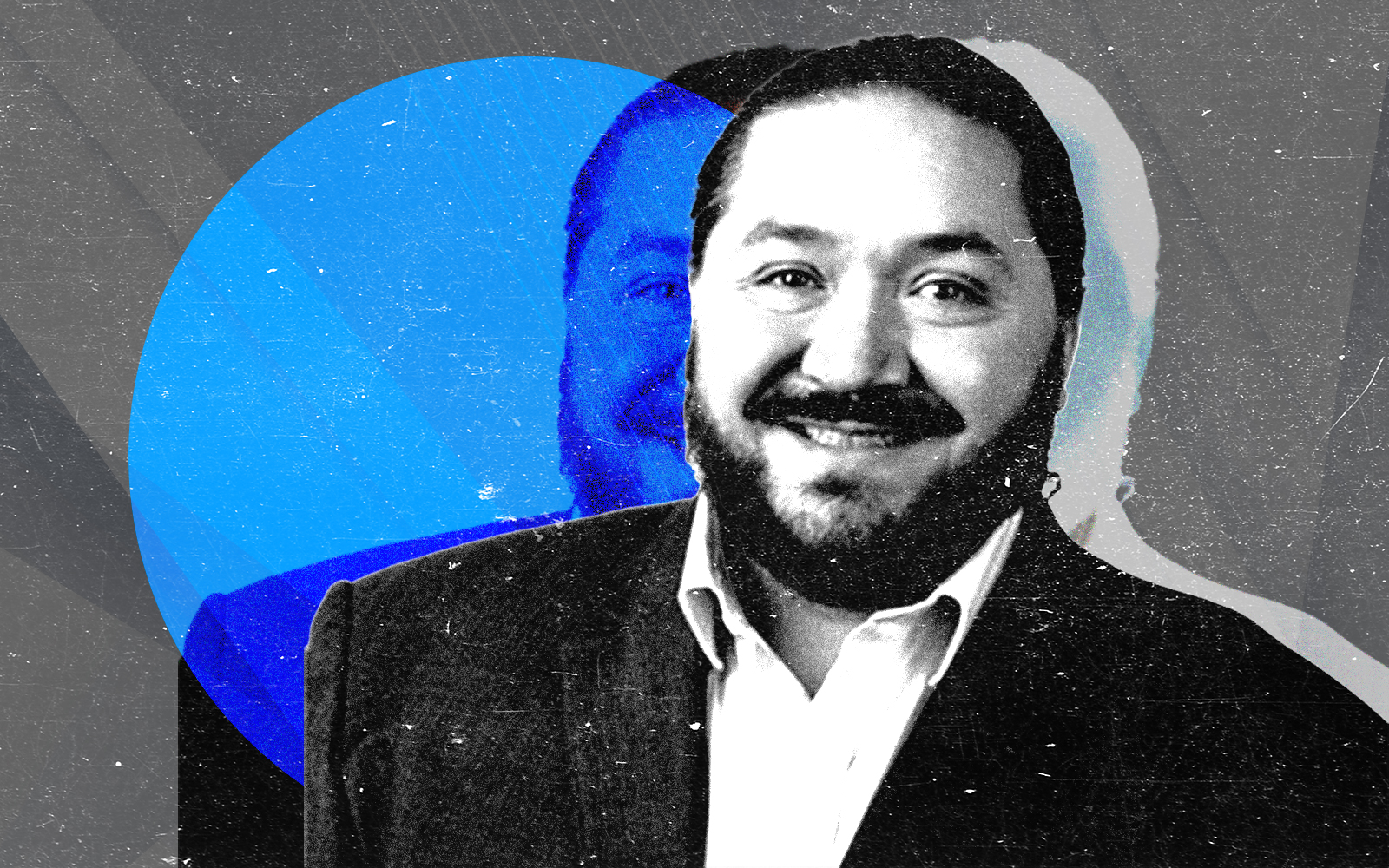

“It took a lot of work and some leaps of faith,” said Community Builders executive Jesse Batus.

The 100,000-square-foot, all-affordable multifamily project with a gym, roof deck and 50 parking spaces had early political support from Richards. But Selvena Brooks-Powers, the Council’s majority whip, sided with the community board, whose vote is advisory but can be influential, especially with a Council election just a year away.

Brooks-Powers hosted a community meeting in July to find common ground with the developer, which had less than a month to radically revise the proposal.

Switching from rentals to co-ops is not like changing a light bulb. It involves reconfiguring the building and the array of funding and subsidies to finance it. Complicating matters, Community Builders, which owns and manages 14,000 apartments and had done a 224-unit, 100 percent affordable rental at Beach 21st Street, had never orchestrated a home ownership program in the city.

“We had a lot of studio apartments in the original plan,” said Jesse Batus, Community Builders’ regional VP. “We removed those because they’re not as marketable for sale. They’re easier to rent, but they’re not as easy to sell.”

The project had an important ally in the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, which had been eyeing the site for affordable housing since Community Builders bought the land mere days before the pandemic hit in 2020.

Nehemiah HDFC, a New York City nonprofit affordable housing developer, helped the project get state funding. It got the Hochul administration to kick in an 11th-hour subsidy for the development, which had previously relied only on city funding.

“If we didn’t have access to it, [the project] would not have been feasible,” Batus said.

Community Builders, a national nonprofit developer, tapped the state’s Affordable Homeownership Opportunity Program, designed for first-time homebuyers, and HPD’s Open Door Program, which funds the development of co-ops and condominiums for middle-income New Yorkers. The rest of the project’s money will come the old-fashioned way: from home sales.

Far Rockaway’s gripe with new housing goes deeper than one project. The community board’s opinion bucks the trend seen in much of the city, where development concerns center on gentrification.

“We have more vacant land and land is cheaper, so money could be made doing affordable and low-income housing but we’d much rather see market-rate housing,” Queens Community Board 14 district manager John Gaska told Commercial Observer.

Building height, a more universal concern in the city, was also an issue. A year ago, the board called for a moratorium on projects higher than six stories. Community Builders had proposed eight.

Read more

The board voted against the project in March, calling it out of context with surrounding one- and two-family homes. Opponents said it would overburden local infrastructure and claimed its schools were at capacity, although the original 106 rentals proposed would likely have brought just a handful of students.

But Mayor Eric Adams has railed against not-in-my-backyard sentiment, saying every community must do its part to solve the city’s housing shortage.

“We got to do the Rockaway project,” the mayor said at a press conference following the project’s approval. “Every day is a new day and we are going to do new things. And those areas that we disagree on, so what? We disagree on them and then we move forward.”