A watchdog group’s flurry of discrimination lawsuits against brokerages and landlords seems to have helped apartment hunters using housing vouchers.

From big names such as Compass to a small-scale Westchester firm, brokerages have settled with the nonprofit Housing Rights Initiative, agreeing to educate agents and landlords and in some cases to fork over tens of thousands of dollars.

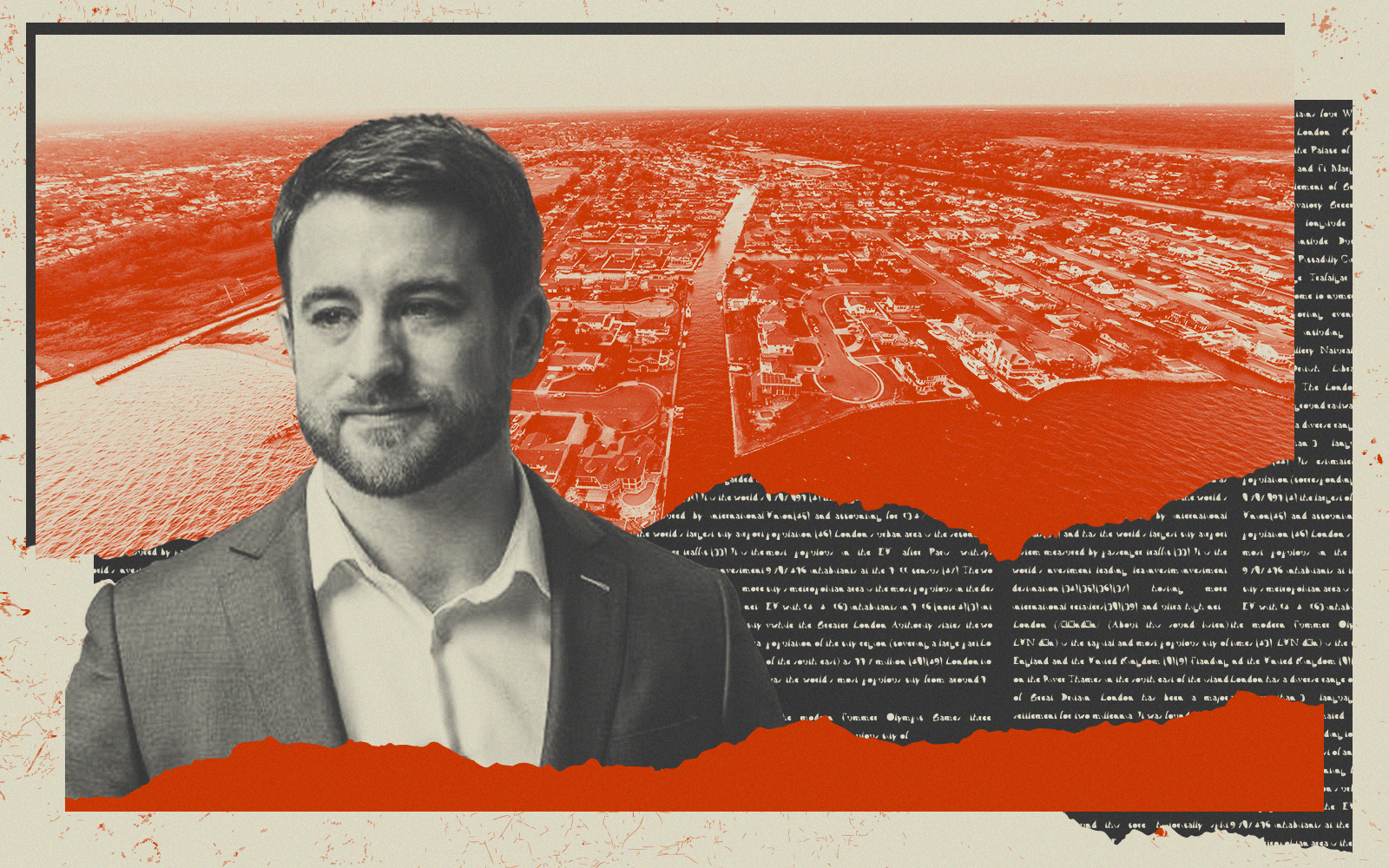

Whether this has deterred brokers and owners from snubbing voucher holders depends on how you measure. But when it comes to explicit discrimination in New York City, the answer is “unequivocally yes,” said HRI founder Aaron Carr.

When the organization started using testers in 2019 to record landlord and broker reactions to rental inquiries from voucher users, Carr said about half of companies would outright refuse, in violation of state and city laws.

“Now it is significantly less than that (approximately 25 percent),” Carr said in an email.

The threat of litigation and bad publicity has been a deterrent. Also, the state in 2019 amended the Human Rights Law to make source of income discrimination illegal, opening the door to wider enforcement.

New York City has had a similar law on the books since 2008 and its Commission on Human Rights opened a Source of Income Unit in 2018. New York Attorney General Letitia James has added her office’s muscle to cases pursued by HRI.

Those sticks have raised awareness among landlords and brokers in New York City.

“Prior to there being any enforcement at all, landlords would just post ads like ‘No Section 8,’ said Stephanie Rudolph, a Legal Aid attorney who has represented prospective tenants in income discrimination suits.

Before the stepped-up oversight and lawsuits, Rudolph, as head of the city’s Source of Income Unit, would call big brokerages to discuss young associates discrimination, only to be “screamed at by their bosses.”

“Now it’s taken very seriously,” Rudolph noted.

But on Long Island, where fair housing nonprofit Long Island Housing Services has won similar settlements, the group’s director, Ian Wilder, said he hadn’t “seen any sign of change so far.”

He said the payouts in those cases typically aren’t punitive, but rather cover the cost of the group’s legal fees and may not be large enough to attract wider attention. An October agreement required an owner to pay just $18,000.

In New York City, “I wouldn’t say that discrimination is decreasing,” Rudolph said. “I would say it’s less blatant.”

Carr said some companies have replaced explicit rejections with subtle discrimination.

Implicit discrimination takes two forms: ghosting and what Rudolph dubbed “frosting.”

“Ghosting is the minute you mention the voucher, you cease getting responses,” Rudolph said.

“Frosting” or “icing,” in dating culture, means pausing the relationship or dragging a person along. In the rental market, a broker or landlord might be slow to return calls, to show an apartment or to provide an application once a tenant mentions a voucher.

“And then if you do end up applying, basically not following up, and if you inquire, hearing that a more qualified applicant had gotten the apartment,” Rudolph said.

Both Carr and Rudolph said groups can test for such implicit discrimination. One would-be tenant might ask to use a voucher and another would disclose employment income, and the outcomes would be compared.

Amped-up staffing by city and state agencies could also help. The city’s Source of Income Unit lost its last employee in 2022. Mayor Eric Adams’ 2023 budget allowed for 17 new positions in the unit, which is part of the Human Rights Commission, Gothamist reported. It’s unclear how many people the unit now has.

A spokesperson for the commission did not offer specifics but noted the unit “is more robust than it’s ever been.” In 2019, it had six staffers. All staff in the commissions’ Law Enforcement Bureau work on source of income discrimination matters, the spokesperson added.

Carr, citing a study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, said building more housing is another way to reduce discrimination.

“When landlords are more desperate to fill units, they become less choosy,” he said.

Wilder said he thinks more fair-housing education is needed for landlords to combat source-of-income discrimination on Long Island. His group is asking municipalities to have landlords sign a non-discrimination policy form as part of the rental permit process.

“Which I think is an easy lift for everyone,” he said, “and is the first step.”

Read more