Stefan Soloviev sprinted after his grape harvester, whipping out his phone to capture the scene. With his son Hayden in tow, the real estate billionaire raced down the parallel row of vines while the giant machine collected grapes reddened by the North Fork sun to be hauled to his nearby winery.

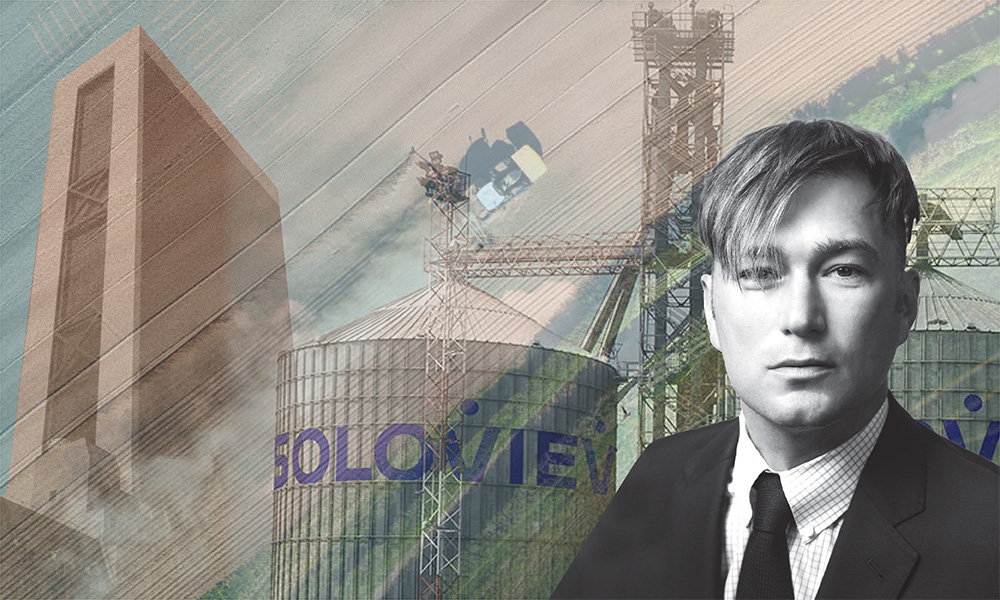

Though best known in New York as the heir to Sheldon Solow’s empire of office and apartment buildings, Soloviev is a farmer at heart. As a younger man, the self-assured real estate scion traded a life of luxury for a tract home in the plains, building a grain production business in part to escape a strained relationship with his father.

That created speculation that the 48-year-old, who took over as Soloviev Group chairman in 2020, might sell his late father’s portfolio to focus his energies out West.

But Soloviev, who spent most of his life spurning the trappings of real estate royalty and at one point disavowed East Hampton, where he owns a home, is reconnecting with the East End of Long Island. He sees big opportunity on the North Fork.

“Since everything’s come together out here, it’s been really cool,” said Soloviev, sporting messy brown locks and a dark tan in the driver’s seat of his blue Ford Raptor. “It’s our No. 1 secondary region and … if there’s ever a region that really I underestimated, it would be this.”

That he looks more like a surfer than an industry titan is no act: He often unwinds with an evening boogie boarding session in East Hampton before heading home for a fine cigar, which he keeps himself primed for by puffing on — but not inhaling — cigarettes during the day.

Soloviev’s increased presence in New York is partly to help his 20-year-old son, Soloviev Group Vice Chairman Hayden Soloviev, grow into his role as head of the company’s Atlantic region, which encompasses the North Fork and Shelter Island. Soloviev believes the area, where he says he’s the largest landowner, can bring the company $1 billion a year in the not too distant future.

Working with some of his 20-plus children (he has not divulged the exact number) is a point of pride for Soloviev, who did not get along with his father. He says any of his children can come work for him, or will be invited to when they’re old enough, but that he is all for them pursuing other careers if they prefer.

Many of Soloviev’s businesses and properties are named after his children. Wine brand Remy, for example, is named after one of his daughters, and Krissie field, where he shot video of the harvester, for another daughter.

Colusa field, an undeveloped North Fork property off Oregon Road, is named after a county in California where three of his children live. The waterfront property is also where Stefan and Hayden have, at different times, brought their college-age girlfriends, a coincidence they’re comfortable joking around about together.

“The majority of my kids, I really am close to them,” said Soloviev. “My No. 1 thing is being happy with my kids.”

Hayden, who oversees a handful of businesses and development projects while also studying politics at New York University, is responsible for the three main pillars of the North Fork operation: Greenwave Landscape and Design, Remy, and Twelve Bridges Real Estate & Development.

The third one will be the most challenging. The North Fork, which runs from Riverhead to Orient Point, is increasingly popular with weekenders but is largely agricultural, and the locals strive to keep it that way.

Two percent of every real estate sale goes to a land preservation fund that buys open space and development rights to prevent housing and hotel construction. And on parcels that remain available for development, restrictive zoning tends to limit what can be built.

Still, when Soloviev talked up his love of farming on stage at The Real Deal’s New York Forum in March, he tossed in, “The exciting thing about the North Fork is that I can build homes. And I’m going to build homes. … We’re going to build some beautiful houses there pretty soon.”

Project approvals on the North Fork often play out in front of resident opposition, which he’s already encountered. Concerns bubbled up last year over his expressed desire to build a boutique hotel, a goal he later said would be joined by 70 homes.

Soloviev’s ex-wife, Stacey Soloviev, who preceded Hayden as head of the Atlantic Region, held a town hall-style meeting in April 2022 to reassure neighbors there were no plans for mass development. Stacey has been reassigned to spearhead Soloveiv’s New York City wine bar operation.

Moving West with Stacey at age 21 had helped cultivate Stefan’s interest in farming, and she portrayed herself as residents’ ally in dissuading her ex from building more than they would like him to. The townsfolk would be thrilled if Hayden took up that mantle.

Southold Town Supervisor Scott Russell previously told TRD he isn’t worried, because about 400 of the 1,000 acres Soloviev owns don’t have development rights.

“When a lot of the land he bought has no development potential, there’s someone that has demonstrated they’re making a commitment to farming,” said Russell. “The problem is when one party comes in and buys up a lot of farmland, it can be unnerving to a community, because they’re not really sure about their goals. But he’s talked and done a lot about hopefully allaying some of those concerns.”

One of Hayden’s first Atlantic region projects was overhauling operations at the boutique Chequit Hotel on Shelter Island, where rooms start at $350 a night and run into the four figures. He brought in a new manager and revamped operations, making sure rooms were cleaned on time and reducing its restaurant’s prices and menu.

He’s getting help in the vineyards from his brother Carson Soloviev, who moved from California to spend more time with dad. The brothers are sharing the family home in East Hampton. Hayden is also splitting oversight responsibilities with co-regional head David McMaster.

Soloviev can be an exacting boss, pressing Hayden about the size and colors of signs and storage containers. But Hayden is free to challenge and overrule him, as he did to conclude a discussion about finding the right gate to drive into Colusa.

Soloviev’s insistent “Hayden, Hayden, Hayden” met with equally insistent “Stefan, Stefan” until the elder Soloviev caved. Hayden turned out to be right.

Soloviev’s increased presence in New York is also partly because there’s no longer a chance of clashing with Solow, who died in 2020. Their strained relationship pushed Soloviev to move out West and change his surname back to the Russian version.

“I used to hate driving in and going in there,” said Soloviev about trekking into the city from East Hampton. “Now, it’s like, I really look forward to it. I look forward to those city days.”

Their father-son dynamic caused Soloviev to reject many of the trappings of real estate royalty: He still avoids the Chequit, for example. But Soloviev has embraced his legacy in the past year.

“Some of my father comes out in me when I’m in the city,” Soloviev said. “He was obviously a genius in a lot of ways and I think I took what he had, and I funneled out the good and the bad from it.”

Soloviev has managed to push occupancy at 9 West 57th Street, a pricey office tower that’s the crown jewel of his portfolio, over 90 percent for the first time. He’s also vying to build the city’s first casino, on an undeveloped 6.7-acre parcel near the United Nations. But you won’t find him shooting video of these properties with the enthusiasm elicited by his grain harvester.

He unloaded the family business’ vast residential holdings to pay the enormous estate tax liability left by his father, who famously resisted selling properties.

Although Soloviev’s New York ambitions are grand, he doesn’t want to be bogged down by them. His passion remains the wheat operation he started out West, which he intends to build into a behemoth that rivals $100 billion operations like Cargill and Archer-Daniels-Midland.

Soloviev started Greenwave, the tree farming operation, as a way to unwind while he lived in the Hamptons years ago.

“I want to drive a tractor — it’s fun,” he said, explaining his thought process at the time. “I don’t really drive a tractor anymore here, but that’s what I used to do for 20-something years … I’d be out here on the phone, going around in a little Kubota or New Holland.”

Read more