Blighted storefronts blanket the Bay Area

Santa Clara County Assessor: “Storefront retail is a dying enterprise”

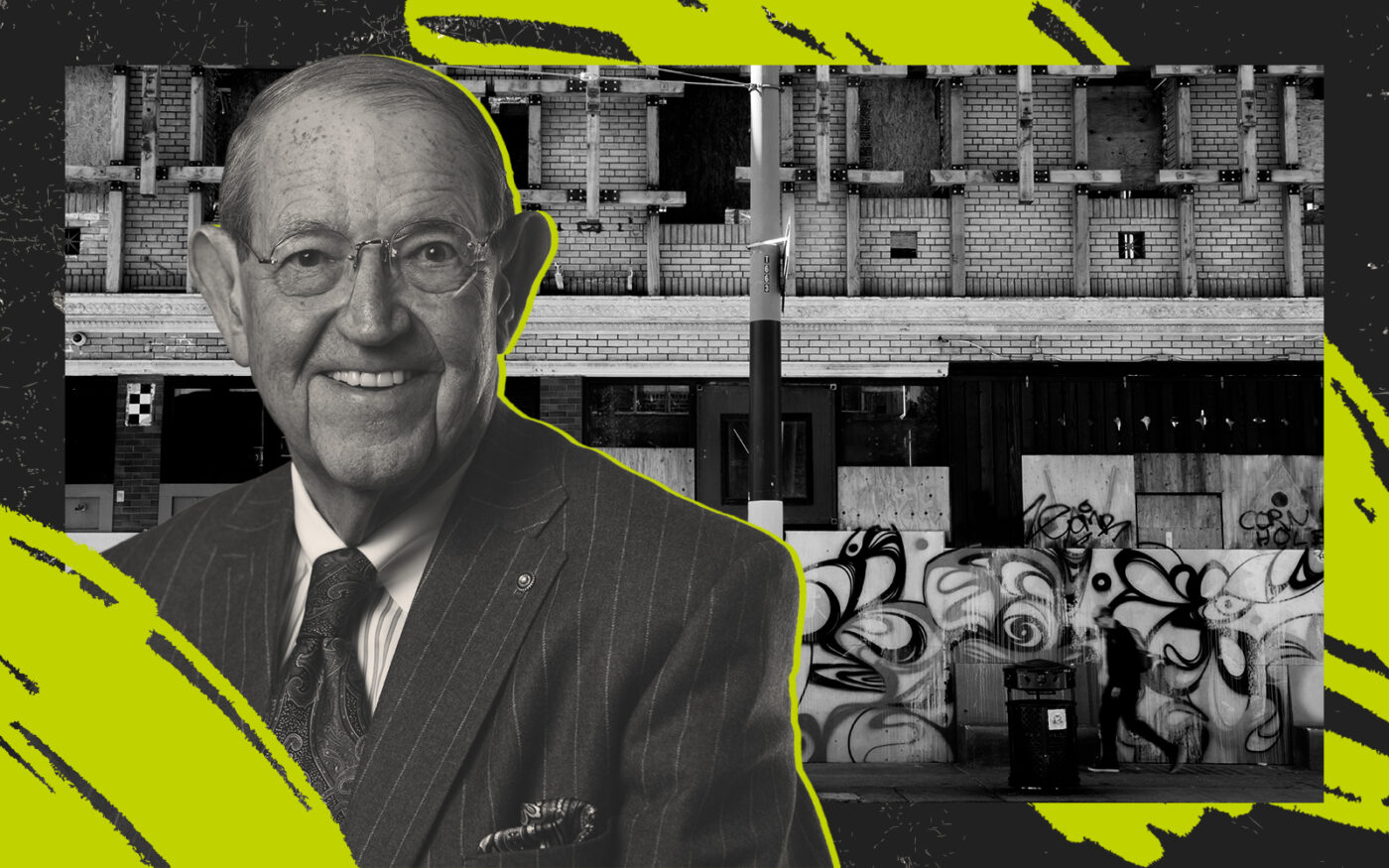

Decaying empty storefronts are popping up in downtowns across the Bay Area.

The boarded up stores from San Jose to Oakland have caused cities to try remedies from grants to punishments to redevelopment, the San Jose Mercury News reported.

Reasons for the blight are many. Vast numbers of buildings were erected in the 1960s and ’70s as the Bay Area transformed from orchards to suburbs, and the cost of updating them deters owners and prospective tenants.

“There’s a whole set of perverse incentives that are conspiring to keep crappy retail spaces vacant for a long time,” Kelly Snider, professor of urban and regional planning at San Jose State University, told the Mercury News. “They will not bounce back.”

Owners of older buildings with low property taxes can still make money with only 20 or 30 percent occupancy, Snider said. Many won’t update them because they can’t afford to or the improvements would raise their property taxes kept low by Prop 13.

Landlords typically want short leases so they can easily hike rents or sell the property, while retail tenants want longer leases, especially if they’ve had to invest in the storefront.

The mismatch contributes to vacancies.

Some deep-pocketed landlords keep spaces vacant while they wait for rents to rise, Max Sander, in charge of retail sales at Kidder Mathews, told the newspaper.

How bad is the problem? No one knows. Cities admit that their vacancy numbers come from commercial real estate reports that leave out properties not currently for lease.

The Bay Area’s retail dynamic upends the classic rule of supply and demand. Despite plunging appetite for retail space, asking rents are rising in the East Bay and remaining level in Silicon Valley and on the Peninsula, data from Kidder Mathews show.

Why rents are not falling with demand remains a “hundred million dollar question,” Sander said. Major landlords sitting on empty space hoping retail demand will rise post-pandemic may offer a partial explanation, he said.

Bay Area cities are seeking various solutions to the storefront problem. Oakland offered grants for small business owners and landlords, and voters there in 2018 approved a special tax for vacant residential and commercial properties.

San Jose this year has allocated $500,000 and expects to spend another $300,000 on “Storefront Activation” grants for improvements, with small businesses seeking to fill empty storefronts eligible for up to $15,000.

A city program imposing quarterly $217 fees on empty buildings downtown appears to have failed to produce any major drop in vacant storefronts, according to a city report.

Ground-floor shops and restaurants in new developments, as emphasized in Santa Clara’s plan, are an essential element for creating community character and culture, Kidder Mathews’ Sander said.

However, Santa Clara County Assessor Larry Stone believes hitching retail to redevelopment projects will backfire, with “vacant storefronts in brand-new buildings.”

City officials are addicted to retail sales-tax revenue, but that golden goose is severely ailing, Stone said. Consumers still want coffee shops, restaurants, hair salons and grocers, but “there’s just not a need enough to fill all the space available,” Stone said.

“Storefront retail is a dying enterprise.”

— Dana Bartholomew