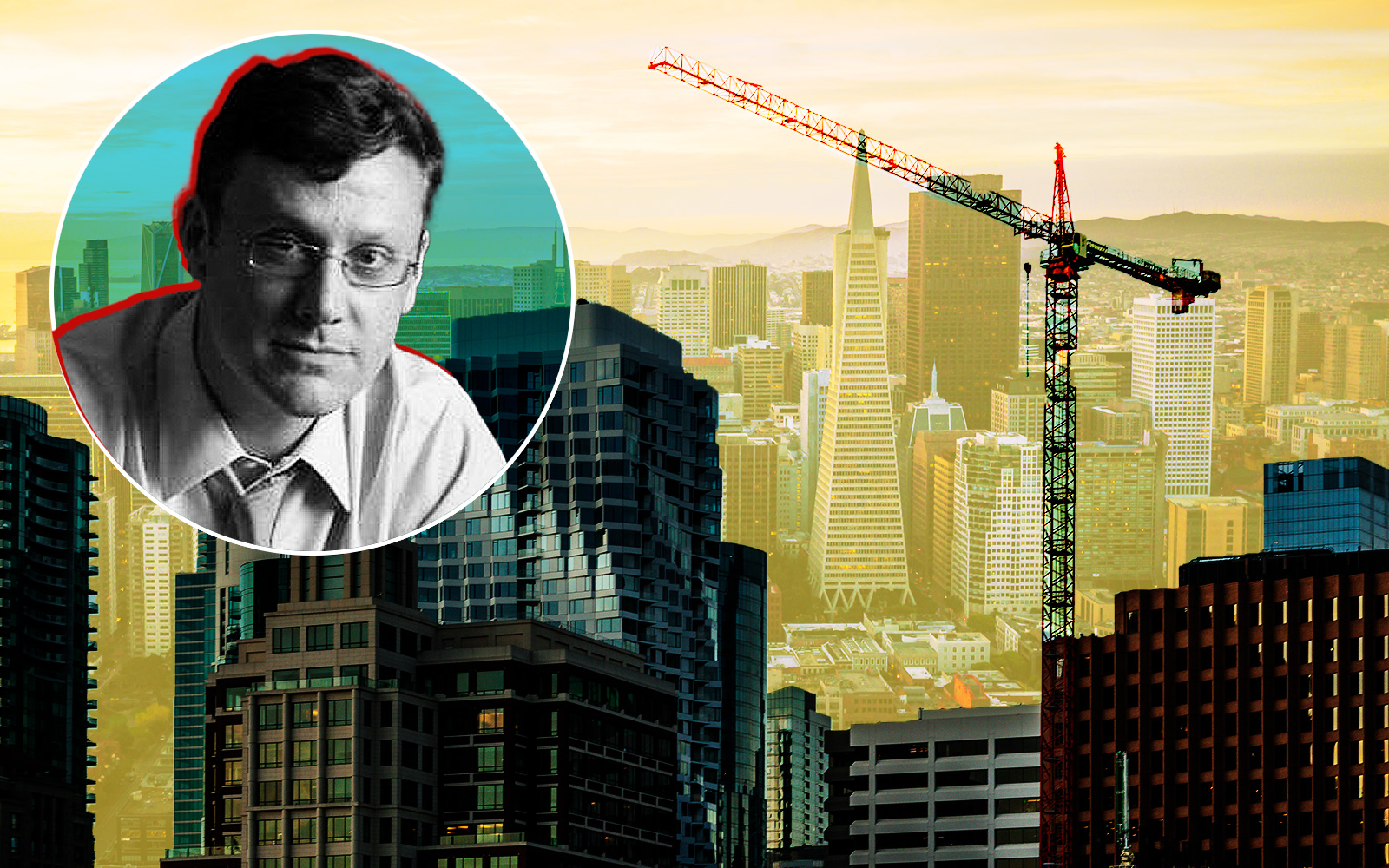

The prohibitive cost of building apartments in San Francisco has led the city’s chief accountant to recommend less stringent rules for the inclusion of affordable homes.

The Controller’s Office led by Ben Rosenfield has suggested the city drop its affordable housing requirement for residential projects to as low as 12 percent to spur the building of more homes, the San Francisco Business Times reported.

But even that may not be enough to encourage growth, with apartment projects in the city too costly to pencil out for developers, according to the city’s chief economist.

The current rate for the so-called inclusionary requirement for affordable homes in market-rate housing projects of 10 units or more is between 21.5 percent and 23.5 percent.

Last month, the Controller’s Office recommended the rate be lowered to between 12 percent and 16 percent, meaning a 100-unit project would require 12 to 16 affordable units.

It also recommended the city lower its in-lieu fees that developers can pay instead of building the affordable homes onsite to between 22 percent and 29 percent of certain development costs.

The in-lieu and off-site fees now run between 30 percent and 33 percent of a given project’s units, and more in neighborhoods such as South of Market, the Mission and the Tenderloin.

The Controller’s Office will likely recommend the new ranges to a city Inclusionary Housing Technical Advisory Committee this spring. The committee meets every three years to advise the city on its affordable housing policies.

Even with the reduced range for affordable housing, building any style of apartments in San Francisco remains unfeasible, Chief Economist Ted Egan told the Business Times.

The Controller’s Office had recommended the 12 percent to 16 percent affordable housing range because it makes some kinds of multifamily development — namely condominium projects in buildings with eight stories or less — feasible.

An analysis by the Controller’s Office said apartment development in the city won’t work even if the city drops its inclusionary requirements to zero, Egan said. Soaring construction costs, coupled with rising interest rates, have rendered many kinds of residential development financially impossible.

“There is no level you could go to that would make our prototype feasible,” Egan said. “There isn’t a number we can come up with.”

In order to encourage developers to build rental housing, San Francisco could include changes to impact fees and other permanent regulatory fees and the timing of when those fees are due, according to the Controller’s Office. Flexible timing means developers can avoid financing fees with debt, lowering project costs and boosting financial feasibility.

San Francisco’s inclusionary rates were set in 2017 and contain regular hikes, according to the Business Times.

Affordable housing rates for projects between 10 and 25 units hit a high of 15 percent on Jan. 1, while rates for projects with more than 25 units are set to climb to between 24 percent and 26 percent by 2025.

Any formal change to the city’s inclusionary requirements would require approval by the Board of Supervisors. The Controller’s Office suggested last month that any policy change last through April 2026.

Read more

Developers have said that inclusionary zoning requirements and fees need to come down if San Francisco wants to meet its state-mandated housing element goals of building 82,000 new homes in the next eight years as lending tightens and construction costs in the city are the highest in the world.

The city also has a mandatory goal of making 46,000 of those homes affordable to moderate and low-income households, and it’s unclear how lowering inclusionary requirements would impact that goal.

— Dana Bartholomew