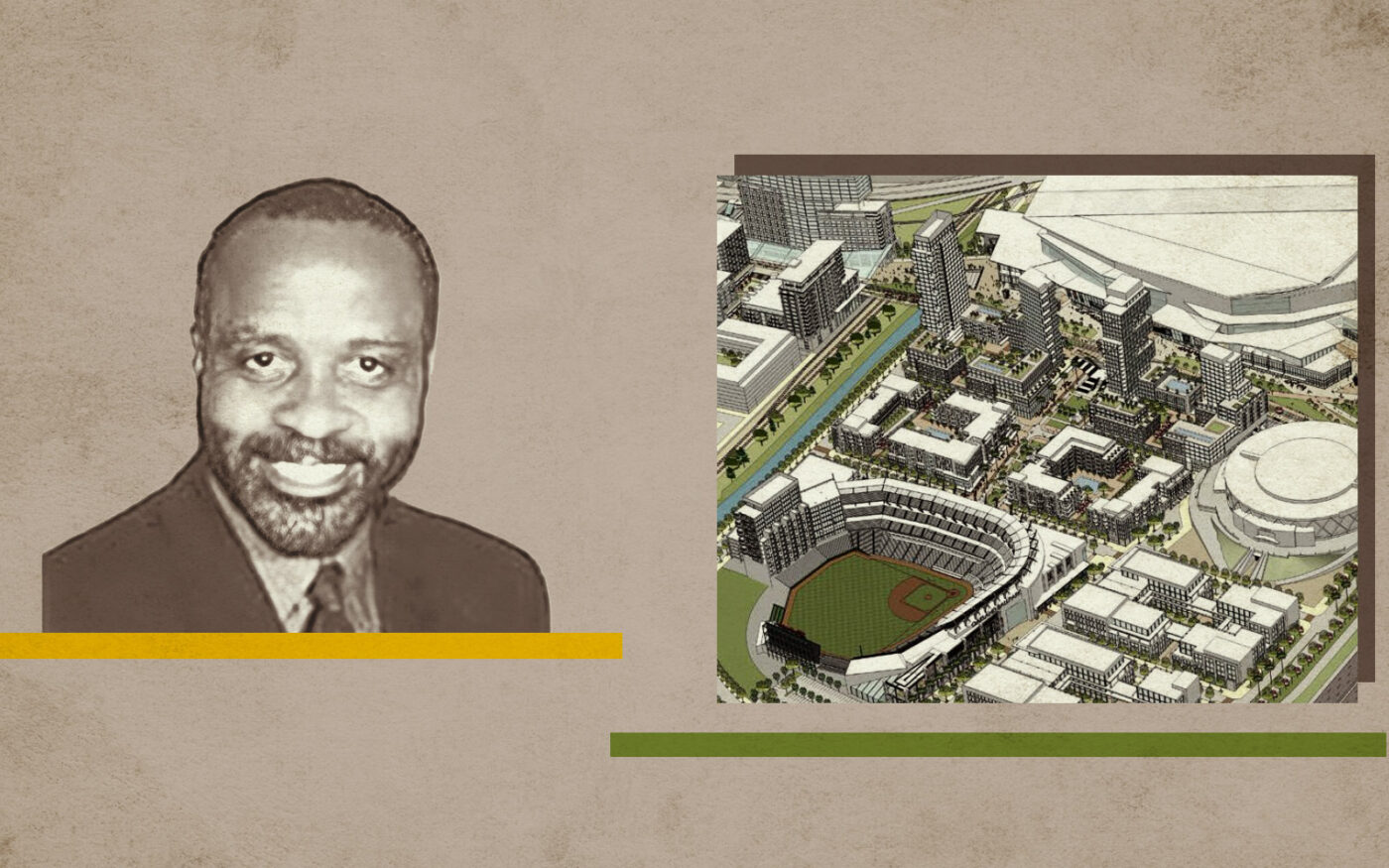

As the managing partner and co-founder of the Strategic Urban Development Alliance, Alan Dones is an integral part of the team of Black investors heading the $5-billion redevelopment plan for the Oakland Coliseum.

That team, the African American Sports and Entertainment Group, recently advanced a bid to take over the Oakland A’s half of the Oakland Coliseum redevelopment, now that it appears the Major League Baseball team is moving to Las Vegas.

“It has always been there as a challenge,” Dones told the San Francisco Business Times of the joint ownership between the A’s and the city when news of the team’s defection broke this spring. “I think this clears the way for us to kind of move forward.”

But the A’s rejected the offer for an undisclosed amount this month and said it had no intention of selling, keeping the Coliseum’s future in indefinite limbo.

Though AASEG founder Ray Bobbitt serves as the public face of the company, and there are other prominent members from the business, sports and civic realms, Dones is the member of the group with the most direct development experience.

Dones did not reply to an interview request but, according to the AASEG’s website, he “has committed to creating a master development strategy, and he has also done extensive planning work on the Coliseum site.”

In his leadership role with SUDA and its construction affiliate ADCo, Dones has developed public projects, such as the major rehabilitation of several Oakland schools, and mixed-use developments, such as Thomas L. Berkeley Square in Uptown Oakland.

He is part of the development team for the Mandela Station project in West Oakland, which aims to turn a parking lot into more than 760 homes and nearly 380,000 square feet of retail, office and restaurants. It was entitled in 2019 but the development team of SUDA and China Harbour Engineering Company has yet to raise enough funds to begin construction.

Dones is also leading development projects in Africa, including the Ghana National Museum on Slavery and Freedom. It will open in 2026, according to the museum’s website.

Development heritage

Dones is the son of the late Ray Dones, co-founder of construction company Transbay Engineers and Builders, as well as the National Association of Minority Contractors, which now has chapters across the U.S. His longtime business partner Joseph Debro called the late Dones “the Martin Luther King of the construction industry” in a 2011 obituary due to his life’s work of parity and opportunity for building tradespeople of color.

“Transbay, under Ray’s leadership, trained more minority workers for union membership than any other construction company in the country,” according to the obituary, published in the San Francisco Bay View.

Dones told the Business Times in 2020 that he was in awe of what his father was able to achieve, including a 1970 partnership with Turner Construction — a first for a minority builder — and Transbay’s 1972 construction of three 12-story affordable housing towers in Oakland in less than 50 working days. It was the first major high-rise constructed by Black builders in the city’s history.

“What they accomplished almost seems like an act of levitation to me now,” Dones said at the time.

Dones wore many hats in the construction industry before getting his general contractor’s license in 1988, from delivering materials to electrical work. That same year he co-founded Rondeau Bay Construction, which grew to five offices across the U.S. and completed more than $70 million in construction projects, according to his website.

He also spent time in the early 1980s pursuing his musical interests, and co-authored two hit singles in 1981, one for R&B singer Debra Laws and another for Latin jazz percussionist Bill Summers. Dones also wrote, produced and performed with Bay Area artists, including a San Francisco-based musical review called “Soul, Style & Sass,” according to his website.

Creativity came into play for Dones’ construction projects as well, and in the 1990s he invented a proprietary method for repairing pipes with minimal surface disruption, which is now used by utility agencies in five states, according to his website. Dones told the San Francisco Chronicle in a late 1990s story about Bay Area businesses investing in Africa that invention runs in his family; his grandfather developed a horse-drawn plow used by Black farmers in South Africa to till rocky soil a century ago, he said.

He has continued his father’s legacy of political activism, co-authoring a victorious mid-1990s Oakland initiative that required the city to adjust race- and gender-based contracting and hiring programs regularly to ensure equitable policies. He also served on the Military Conversion and Reinvestment Commission, advocating for policies to promote female- and minority-owned firms competing for military base conversion projects.

Dones co-founded SUDA in 2000 with his father. When the company broke ground on the nearly 250,000-square-foot mixed use Thomas L. Berkeley Square in 2004, it helped bring his family’s story full circle. It also exemplified just how little had changed for Black developers and construction companies more than 50 years after his father first made his mark, he told the Business Times.

“We have not yet, as Black contractors, been able to get back to that place, of constructing high-rise buildings on our own,” he said. “There was a moment of hope and expectation … but we still haven’t gotten back to that point.”

Read more