Evanston made national headlines a few weeks ago when its City Council passed the nation’s first government reparations program for African Americans, in a move to address racial disparities in wealth caused by the deep legacy of slavery, segregation and discrimination, both explicit and unwritten.

How fitting it was that this program, which will provide $25,000 in home improvement grants and mortgage assistance for descendants of longtime Black Evanston residents, passed shortly before April’s Fair Housing Month. We take this moment to celebrate the important progress that has been made in the fight for fair housing, while recognizing the considerable work that remains.

For many of us, the term “segregation” probably brings to mind black-and-white photos from the 1960s, and the eventual triumphs of that era as civil rights became legally protected. Indeed, any form of discrimination based on race, among others, in housing is clearly illegal today. However, racial disparities did not magically disappear with the passing of the Civil Rights Act, and it’s important to understand why. While many of the causes behind them are rooted in pre-civil rights era history, those wrongs still have not been fully “righted” — which is the entire impetus behind Evanston’s bold program. As it pertains to housing, redlining is an illustrative example of a wrong that can still be seen in modern society.

To review on redlining, the inability for Black Americans to purchase homes in many communities that they wanted to live in, solely based on the color of their skin, forced them to live in “redlined” areas. These areas were deemed poor investment grade for lenders, so Black families were often unable to be approved for a mortgage at all. Decades of renting instead of owning cost the next generations of these families untold sums of generational wealth, that others were able to enjoy.

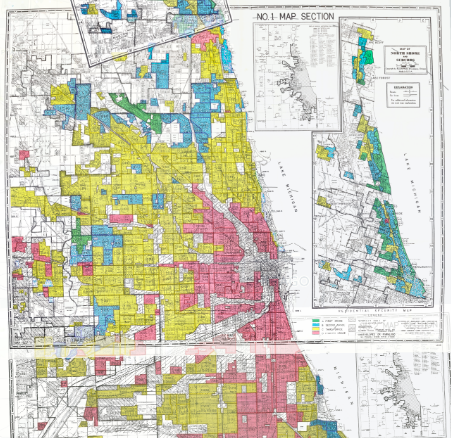

Image: Mapping Inequality/University of Richmond

The above 1940 Chicago redlining map shows the areas deemed “hazardous” in red, followed by “definitely declining” in yellow, “still desirable” in blue, and “best” in green. As you can see, the vast majority of the city and inner suburbs fell into the first two categories, while the pristine blue and green areas were primarily farther out. While Chicago is known as a particularly segregated American city even now, a similar story played out in nearly every major metro area in the nation. While demographics have changed significantly in the 81 years since this map effectively dictated which races were welcome where, the impact of this once-widespread practice among others can still be seen in varying ways. Many formerly-redlined areas have simply never recovered, while others have gentrified so aggressively that longtime residents have left.

The legacy of redlining is one of the leading causes for today’s extreme racial wealth disparities in the United States. While in 2021 anyone can legally purchase a home in wealthier areas regardless of their racial identity, the cycle of poverty that disproportionately impacts minorities remains rooted in this decades-long deficiency of generational wealth building. This is one form of economic segregation, which, as it pertains to housing especially, is a battle that has intensified in recent years.

While 1960s legislation and subsequent additions over the years have protected many rights as we head into the 2020s, more work remains to address these past inequities that have not been as directly addressed.

However, we must also celebrate the early pioneers who paved the way for today’s next steps. In the 1960s, much of the local real estate industry was wary of civil rights proposals. But it was the leader of Chicago’s oldest and largest real estate company at the time, Baird & Warner President John Baird, who became a crucial advocate, testifying to City Council in 1962 to push for fair housing. Chicago’s 1963 Fair Housing Ordinance would follow a year later. His fight would continue through ups and downs, as ours does now. But this Fair Housing Month, we are reminded of the importance to continue the fight.

You can learn much more about the fight for fair housing in a new exhibit at the Elmhurst Art Museum. The exhibit runs through June 20 and tickets are $15 for adults, $12 for seniors.