Trending

Inside Nate Paul’s bankruptcy jiu-jitsu at Braker Business Park

How MIG Real Estate beat out Karlin to buy the Class B offices

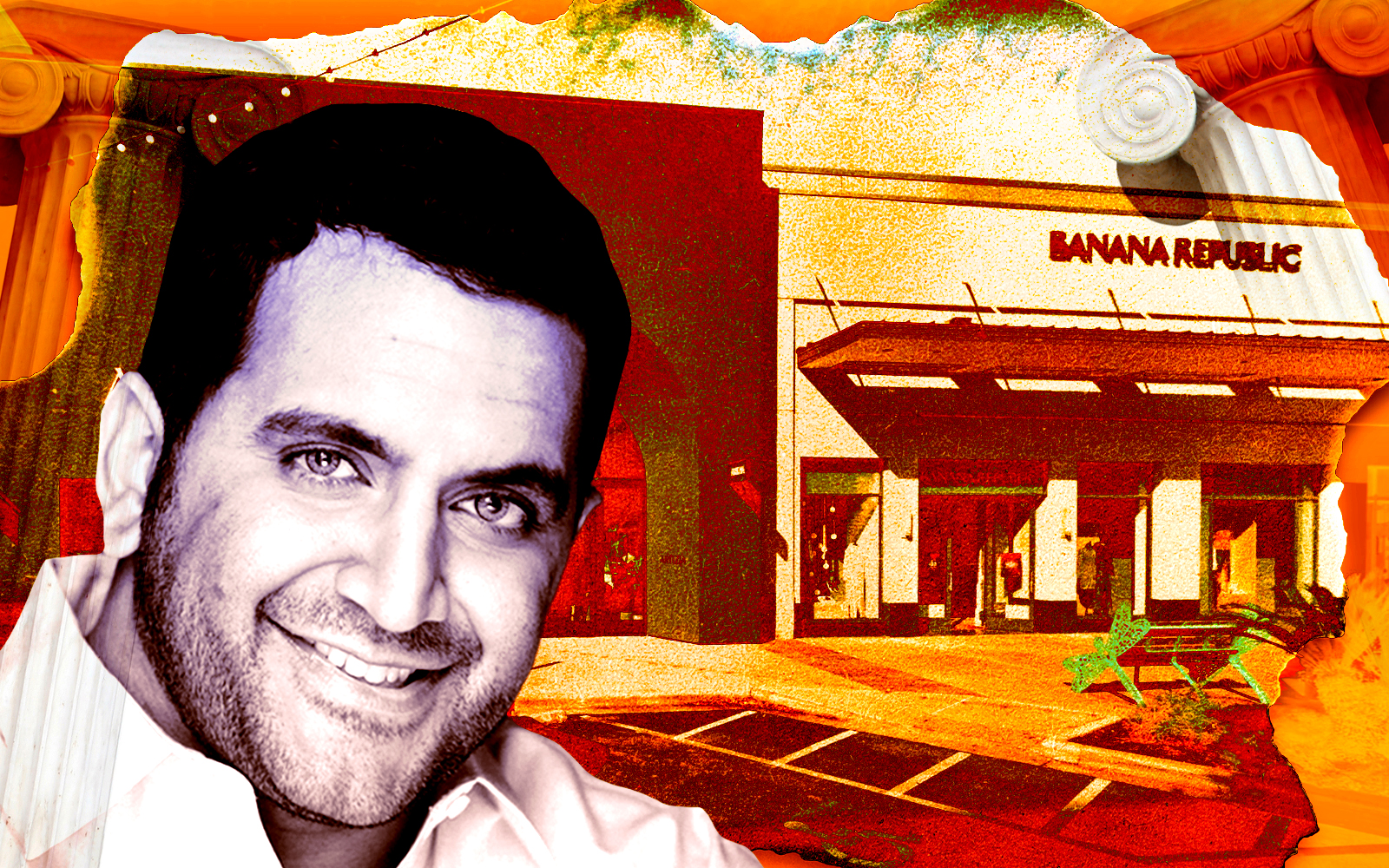

As Austin developer Nate Paul has lost and sought to rebuild substantial chunks of his Austin property empire, he left a trail of bankruptcy filings in his wake. Earlier this week, California-based MIG Real Estate bought Paul’s Braker Business Park, a portfolio of 13 office buildings and a strip mall formerly owned by Paul’s company, World Class Holdings. The investor, based in Newport Beach, beat out Karlin Real Estate and four other bidders for the properties, which only came to market after months of legal maneuvering.

The Braker Business Park deal is one of the clearest examples yet of what happens when a lender tries, and fails, to take control of a World Class property through foreclosure. It has also, inadvertently, brought about a battle between the firms of two California billionaires with growing interest in Texas, Karlin’s Gary Michelson and MIG founder Paul Merage.

The saga started in February 2019, when JPMorgan gave a $71 million mortgage to World Class, or more specifically WC Braker Portfolio, a shell company that owned the properties. That loan was secured by the properties themselves, but Paul also set up a second LLC, WC Braker Portfolio B, which owned all of the membership interests in the first LLC.

Paul pledged those membership interests as collateral for a $29 million mezzanine loan, also given by JPMorgan in February 2019. JPMorgan almost immediately transferred the mezzanine debt, and in 2021, Karlin bought the note.

Both the senior and mezzanine debts came due in March 2021 and were not paid in full, according to court filings by Karlin, which declined to comment for this story. Karlin attempted to foreclose on the membership interests, but around the same time, JPMorgan tried to foreclose on the properties themselves, which would have left Karlin with little in the way of actual assets.

To salvage the investment, Karlin bought the mortgage from JPMorgan in April, a month before the scheduled foreclosure sale.

In May, just before the foreclosure would take place, Paul put the property’s ownership entity into bankruptcy to avoid the sale. An attorney for Karlin called Paul a “serial abuser of the bankruptcy process” in filings, accusing the developer of using bankruptcy as a shield against foreclosure at dozens of properties around Austin.

The bankruptcy filing by Braker’s ownership entity lists 11 affiliated bankruptcy cases, and over the past three years, World Class has filed at least two dozen bankruptcies.

After it failed to foreclose on the buildings themselves, Karlin then tried the same thing with the mezzanine debt, which was secured by the second LLC’s interests in the ownership entity. But Paul juked that foreclosure too, putting the second LLC into bankruptcy. The second bankruptcy came on the same day that a UCC foreclosure sale of the membership interest in WC Braker was scheduled to begin.

After two attempts to take control of Braker Business Park at two levels of the debt stack, Karlin had come up empty. It could still get the property, but it would have to do it the hard way: an open auction.

Battle of the Bidders

The Braker portfolio has some warts.

Austin has one of the highest return-to-office rates in the country, if card-swipe metrics are to be trusted. And the Domain has pulled in some of the city’s biggest commercial tenants. The portfolio is about 60 percent occupied, leaving room to increase cash flow, and the property’s 40-plus contiguous acres have redevelopment potential. Part of it is already entitled for multifamily development.

But the offices themselves leave much to be desired. Built in the early 1980s, they are mainly Class B, office-and-warehouse flex space. In the post-pandemic, so-called “flight to quality” leasing environment, Class A space has been the hot asset. Older buildings with few amenities, like those in the Braker portfolio, are a trickier sell.

“On the one hand, Austin is a hot market. But on the other, office space is not,” said Harold Bordwin, co-president of Keen-Summit Capital Partners, the marketing agent for the property’s bankruptcy trustee. “Is the hotness of Austin going to prevail over the not-hotness of office?”

As is the case in most properties sold out of bankruptcy, bidders on the Braker portfolio needed to be able to close on a shorter timeline than they would in a standard property acquisition. The portfolio closing happened just 10 days after the auction, and MIG paid all cash. Potential buyers essentially needed to complete their due diligence and have funding lined up before placing a bid.

Before the property was marketed, Karlin signed a stalking horse contract to place a credit bid of $75.5 million.

To make it to the auction on Feb. 14, bidders had to put up a 10 percent deposit. Given Karlin’s minimum bid, that meant being liquid enough to write a check for nearly $7.6 million. By the bid deadline in early February, five bidders other than Karlin had submitted deposits. While Paul has been buying back some of the properties he lost, he was not a bidder on the Braker portfolio, according to Bordwin.

MIG opened with an $80 million bid. Two hours and 89 bids later, it had the highest bid at $102.25 million, which put it $250,000 ahead of Karlin’s highest offer.

MIG was not the buyer Keen initially expected. Based in Newport Beach, California, the firm owns more properties in Colorado and Arizona than Texas. “There were a number of well-known real estate investors who we reached out to, but the marketing brought people to the table who we did not know. MIG was one of those,” Bordwin said.

MIG already owned three flex buildings near the Braker portfolio, and it owns three in Colorado and one in Arizona, according to its website.

Anything over Karlin’s $75.5 million in senior mortgage debt would go to paying the unsecured creditors and expenses of the case. After that, the excess money goes to the secured creditor for the mezzanine debt — again Karlin — but given that the sale price is less than Karlin’s overall amounts owed on the two notes, at least $104.7 million after interest, the company figures to still be slightly in the hole on the deal.

Karlin isn’t the only high-profile firm trying to get a piece of the proceeds. Earlier this week, Endeavor Real Estate Group filed a lawsuit to freeze payouts from the Braker sale, alleging that a 2016 leasing and management agreement it signed with World Class gives it a higher priority claim than Karlin has from its mezzanine note.

Kevin Stiles, MIG’s director of investments, said the firm will continue to operate the property under its present use, and that it is looking for similar investments in the Austin area and Sunbelt states. The Domain has rapidly developed in recent years, and is particularly popular with technology companies. A recent change to the zoning code boosted allowed densities in the neighborhood, allowing for floor-area ratios of up to 12-to-1.

Paul, who did not return a request for comment, told The Real Deal last year that he plans to keep developing and buying real estate in Austin for decades to come, and he has managed to retake some of his old assets since then. But at least for now, after months of hanging on, the Braker portfolio is finally gone.