At 24 years old, Nate Paul bought the Spaghetti Warehouse building, a handsome brick building in downtown Austin. At 34, he lost it to a group of creditors after a yearslong foreclosure battle.

The story of how that landmarked trophy at 117 West 4th Street and a slate of others slipped away, despite Paul’s frenzied attempts to hold onto them, is now at the center of one of Texas’ biggest political controversies in recent memory.

On May 27, the Texas House of Representatives voted to impeach the state’s Attorney General, Ken Paxton. One of the claims against Paxton, abuse of the opinion process, alleges the attorney general used his powers to help Paul delay a foreclosure auction of some of Paul’s properties, including the Spaghetti Warehouse building, his first major acquisition.

The saga began in the summer of 2020, as Paul faced mounting lawsuits over his unraveling property empire. Paul had already once delayed the Spaghetti Warehouse’s foreclosure, which was brought by a group of creditors including Texas car dealer Bryan Hardeman, by convincing the court to grant a temporary restraining order in July. When the court declined to extend the order on July 31, a Friday, it left Paul with just a long weekend to stop the sale.

Enter Ken Paxton.

That evening, the attorney general allegedly asked his staff to look into whether foreclosures were allowable under pandemic restrictions. Using that information, the team could draft an opinion, a form of legal guidance periodically issued by the attorney general to help understand thorny questions of state law. Paxton allegedly demanded that the opinion be written by the end of the weekend, a timeline that the House investigation committee’s counsel Mark Donnelly called “extremely abnormal.”

Of all 36 attorney general opinions requested and issued in 2020, the average opinion took 127 days from request to release, an analysis by The Real Deal found. Two other opinions released that year took 3 and 4 days to turn around, but in the vast majority of cases, it was a much longer affair. Some 30 opinions took longer than a month, and 24 of those took longer than 100 days.

The process typically involves extended research, consultation with experts, and approval from several members of the attorney general’s office. The foreclosure research ultimately resulted in an “informal opinion” — legally distinct from the official opinions tabulated above — and only has one signature, that of Ryan Bangert, a former senior staffer in Paxton’s office, who eventually became a whistleblower against the attorney general.

Opinions also require an official request from someone of stature, like an elected official, a state agency or a prosecutor. Each step of the process is clearly, publicly documented on the attorney general’s website, where anyone can access all of his opinions, as well as the written requests that prompted them. The informal opinion on foreclosures during the pandemic is not on the site.

According to investigators, Paxton simply gave his staff a phone number to contact for the request. When contacted, that person was “completely unfamiliar with the matter,” and the staff instead reached out to State Sen. Bryan Hughes to generate a request.

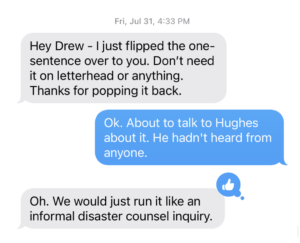

In a text that night, a member of Paxton’s staff asked a member of Hughes’ staff to send an inquiry about foreclosures to the attorney general to serve as the official request.

“Don’t need it on letterhead or anything. Thanks for popping it back,” the text from Paxton’s staffer reads.

As whistleblowers from Paxton’s office later alleged, the attorney general’s staff initially concluded that foreclosures were not blocked by Covid restrictions. But Paxton made it clear to them that “the opinion needed to change,” House investigators said this week.

At 1 a.m. on Aug. 2, barely two days after Paxton asked his staff to look into the foreclosure issue, the attorney general’s office issued its “informal opinion.” The recommendation found that foreclosure auctions, which take place outside the courthouse in Travis County, should not occur due to pandemic restrictions on in-person gatherings. At the time, many outdoor meetings were limited to 10 attendees. Further, any foreclosure auction that took place in which a qualified bidder could not appear due to that restriction was therefore not a “public sale” as required by Texas code, so even an auction of the correct size could be faulty.

The opinion relied on some semantic sleight of hand. The federal government considered real estate services to be essential work, and the governor’s pandemic restrictions specifically exempted essential workers.

The informal opinion contained wording that a foreclosure auction was not a “dedicated” real estate service, and therefore not protected by the carveout. Never mind that the word “dedicated” doesn’t appear in the government’s 20-page memo listing essential workers

Adding to investigators’ and the whistleblowers’ concerns, Paul’s lawyers showed creditors a copy of the opinion the following day.

Rep. Ann Johnson, a Democrat from Houston and vice chair of the committee that led the House investigation, called the opinion “a complete violation of the processes that [are] to be followed,” noting that it was “issued within two days solely to the benefit of Nate Paul.”

The opinion couldn’t save the property, but that August, Paul’s attorneys used it to try to stop foreclosures on at least a dozen properties, according to the investigators.

Paul put the Spaghetti Warehouse’s ownership entity into bankruptcy just before the foreclosure, delaying the sale further. Hardeman and his team proceeded to buy the notes on several World Class properties, leading to a skirmish Paul recorded at a 2021 foreclosure auction in which he claimed to have the money to buy one of his properties in full.

Paul, who did not respond to a request for comment, has called the moves a fraudulent scheme to take his properties. “Put yourself in my shoes. People buy loans on your properties, try to attack you, and you put up ALL of the funds to pay them off to get away from them, and they refuse to accept payment. This has happened on several properties,” Paul wrote at the time on LinkedIn. Hardeman has maintained that nothing is wrong with his actions.

In July 2021, the property finally went up for auction. The lenders won with a credit bid just shy of $9 million.