To make it in real estate, you need to know a guy.

Not any one guy in particular, but at some point, you’ll need an expeditor who can arrange permits at NASCAR speed, or a subcontractor who won’t bullshit you on lumber prices, or a broker with off-market scoops.

Favors are a universal currency in the business world, standard operating procedure. There’s nothing necessarily crooked about them, and often, they are just a reward for hustle. But when favor-trading creeps out from the private sector into relationships with public figures, things get sticky.

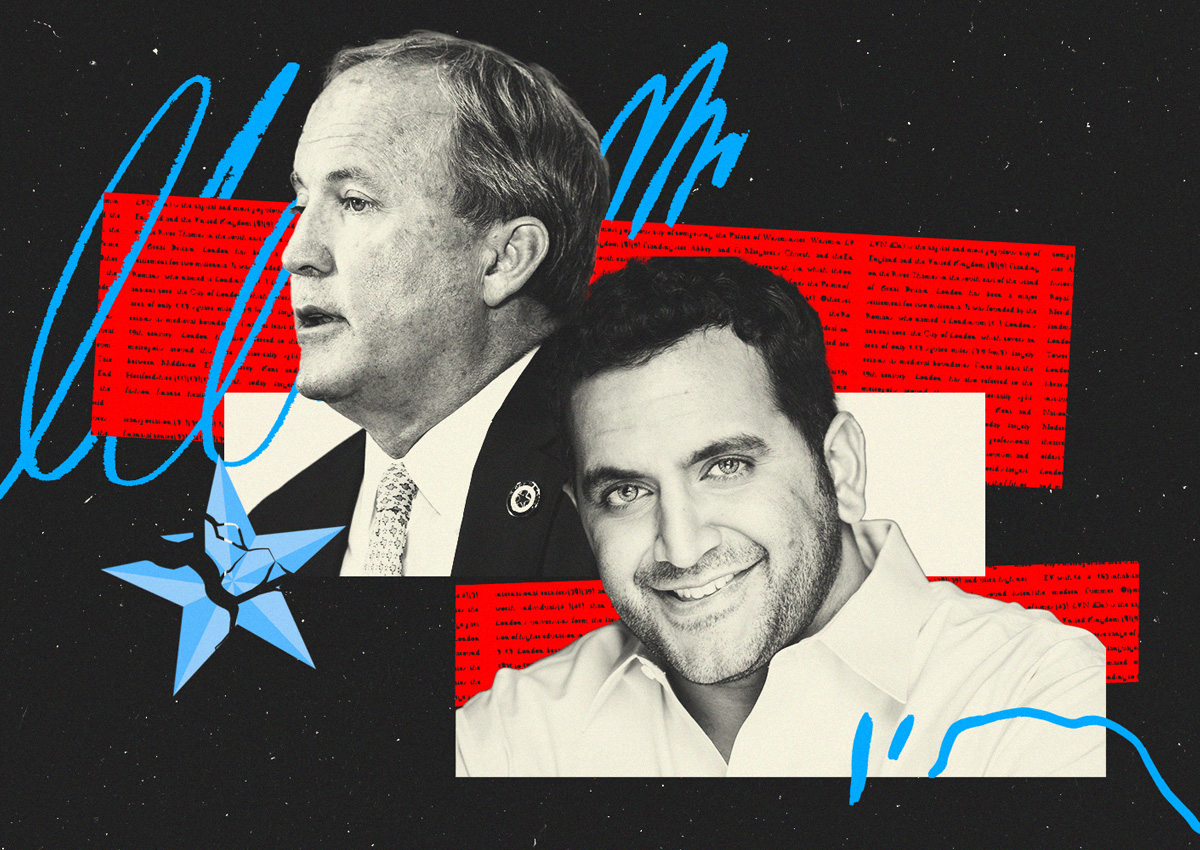

One such relationship dominated the Texas political world last week as Attorney General Ken Paxton faced an impeachment trial over his ties to Austin real estate investor Nate Paul. To be clear, Paxton was acquitted of all 16 charges, from abuse of office to bribery. But the fact that the Texas House of Representatives impeached him, and that a Senate trial happened at all, is a stunning outcome for a top Republican in a GOP-dominated legislature.

When, like Paul, you’re under federal investigation and facing multiple foreclosures, the state’s top cop is a great guy to know. And Paul and Paxton knew each other well. No one disputed that.

Real estate is a relationships business, and the best operators often have a sixth sense for the favors they can give. That way, they don’t just know a guy; the guy owes them one, too.

The pair met several times at Polvo’s, which, while not exactly a power lunch spot, nonetheless put the two across a table with some food in between them. Many real estate deals have been struck in similar situations.

Tony Buzbee, one of Paxton’s attorneys, rightly pointed out that a lunch here and there is not a bad thing.

“If a lunch is a bribe, then boy howdy, do we have a problem here,” Buzbee said.

But the lines between an interaction, a favor and a bribe are blurry. A mind-numbing amount of the trial was spent litigating whether a particular act counted as a favor, and if a favor counted as a bribe. Usually, the defense’s argument rested on the fact that Paul did not get what he wanted.

According to the defense, Paul was “madder than a hornet’s nest” and threatened to sue the attorney general’s office when it didn’t do what he wanted.

But a favor is not a contract — its terms are inexact, subject to change depending on one party’s needs and the other’s capabilities. A favor doesn’t guarantee results, either — often, it just means that when the time comes, you’ll have a foot in the door.

When Paul felt the FBI had tampered with the search warrant for his home and business, he had a line to Paxton. The attorney general repeatedly asked his deputies to look into the case, setting up several meetings between Paul and Paxton aides, even when they felt Paul’s theories were bogus. They ultimately refused to investigate the claims further, but results aren’t guaranteed when you ask a favor.

“The only thing that [Paxton] did was say ‘let’s find out the truth,’” Buzbee said in his closing argument. The point is that Paul was able to ask for help in the first place.

Just about everyone has something he would like to yell at the government about. Paul was able to have those shouts heard. “We were devoting far more resources to Nate Paul than we ever should have, given the importance of those issues,” Ryan Bangert, a former top aide to Paxton, said at the trial.

When Paul faced imminent foreclosures on several properties across the state, Paxton’s office issued a “midnight opinion” advising against foreclosure sales due to the pandemic. Paxton’s defense pointed out that the informal opinion didn’t actually prevent Paul’s properties from being seized — he put the ownership entities into bankruptcy, automatically halting foreclosures — but just one day after the guidance was issued, Paul emailed it to Amplify Credit Union, one of the foreclosing lenders, its CEO said at the trial.

All the other alleged misconduct that senators felt did not justify impeachment — the Uber alias, hiring Paxton’s mistress, being oddly looped in on Paxton’s home renovations — sound, in a business context, like favors. But they allegedly happened between a businessman and a politician who is theoretically supposed to abstain from them.

Just as the acts themselves were complicated by politics, so was the impeachment process. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick made several efforts to demonstrate that he was an impartial judge who took the process seriously: He swore in each senator individually on the Sam Houston Bible, a state talisman on which each of the state’s last governors has sworn his oath. He appeared measured, cautious and calm on the dais as he oversaw the trial.

But impeachment trials are by definition political, not criminal. The bar for impeachment is vague, and conviction would have barred Paxton from holding office, not put him behind bars. Politicians trade favors too, and by sending its impeachment vote to the Senate at the tail end of the session, the House tried to cash a favor it hadn’t earned. Speaker Dade Phelan, a real estate investor himself, spent much of the legislative session in a nasty spat with Patrick over property tax reform. There’s little love among the two, and you generally don’t do favors for your enemies.

Patrick finally shared his thoughts on the trial once the votes were counted. His biggest complaint was with the House.

“The Speaker and his team rammed through the first impeachment of a statewide-elected official in Texas in over 100 years,” Patrick said from the dais. “An impeachment should never happen again in the House like it happened this year.”

Patrick then praised a speech given during the House vote by Rep. John Smithee, one of the 23 members to vote against impeachment, railing against the process. Patrick called it “one of the most honest and courageous speeches I’ve ever heard in the House.”

“That to me sounds like an endorsement for a Speaker candidate,” Scott Braddock, a longtime Texas political journalist and analyst, said on a Houston Chronicle podcast.

Real estate, with its permit approval mazes and zoning gauntlets, is intimately wrapped up in politics. Despite what campaign fundraisers and their beneficiaries will tell you, there’s a reason real estate titans routinely top campaign donor lists. No shrewd business person lights money on fire.

Impeachment prosecutors tried to make a big deal out of Paul’s $25,000 contribution to Paxton’s campaign in 2018. A fat contribution does not mean a donor will get what he wants. But it does mean that the politician will call the next time he is running for office.

He needs money, and he knows a guy.

Read more