Much of the area surrounding the old headquarters of the Austin American-Statesman newspaper isn’t pretty, but to a developer, it may as well be the Mona Lisa.

Situated on the south shore of Lady Bird Lake and wedged between downtown and trendy South Congress, the parcels are currently home to sprawling parking lots and old apartments. Major developers are interested in the area, though, and those eyesores have become some of the most valuable development sites in Austin.

Those aiming to redevelop the area, now called the South Central Waterfront, suffered a major setback this week.

The city had aimed to use a powerful financing tool to build out infrastructure in the area, which suffered for years from frequent flooding. But neighborhood activists won a lawsuit against the City Council, claiming that its plan to establish a Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone encompassing more than 100 acres in the area broke state law.

The city established the TIRZ in late 2021 to encompass 118 acres along the south shore of Lady Bird Lake. It would have diverted an estimated $354 million dollars in property taxes raised within the zone to help build infrastructure, like streets, parks and affordable housing. Without the help, developers will face hurdles in making their projects pencil.

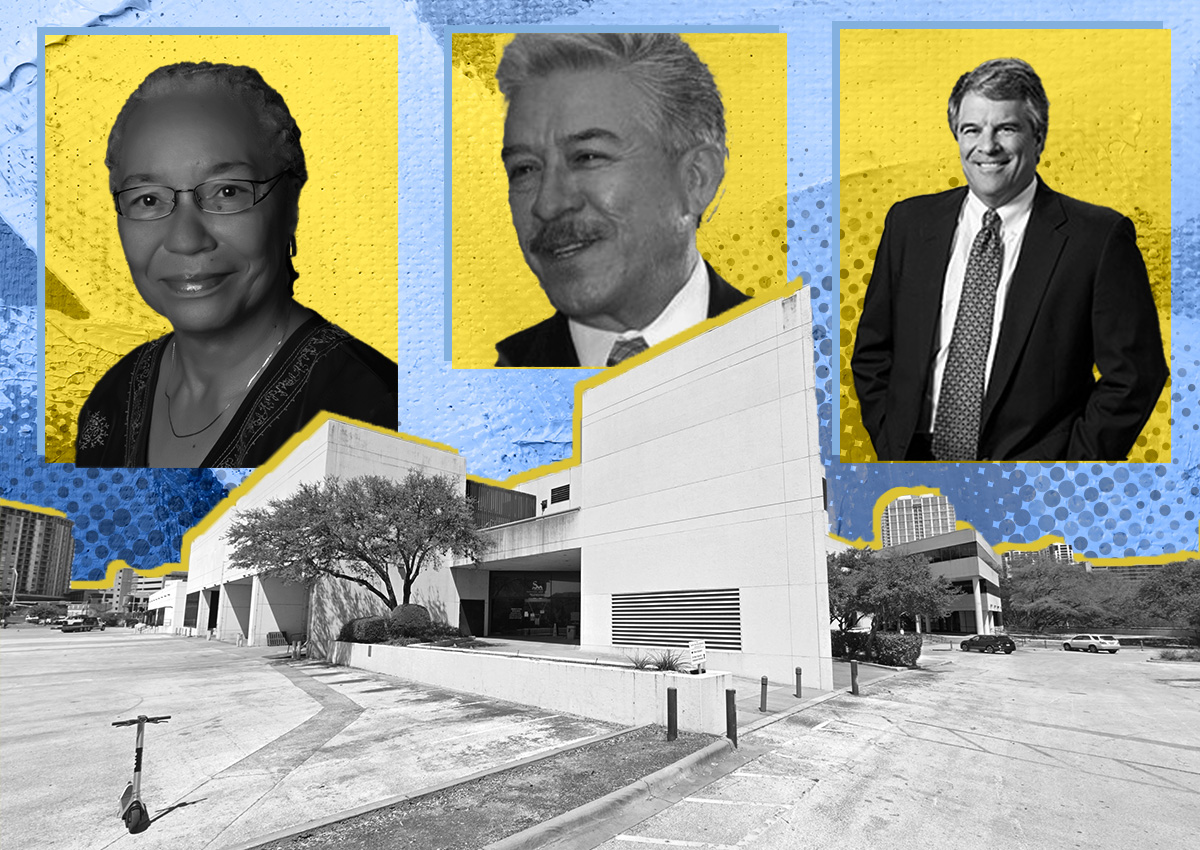

“It’s both terrible and fine,” said Felicity Maxwell, an Austin city planning commissioner and member of the board at AURA, an urbanist organization. “They won this round, but we’re going to win the war.”

Maxwell is working on a regulating plan for the neighborhood, which will come before the City Council early next month. As she and her colleagues have worked on that development framework, they have known that the TIRZ was under threat and planned around it. Maxwell expects the large developments still planned in the area will help raise funds for neighborhood benefits like affordable housing and parks.

The most significant development planned for the neighborhood is Endeavor’s massive redevelopment of the old American-Statesman campus. That 3.5 million-square-foot project calls for 1,378 apartments, 1.5 million square feet of office space, a 275-key hotel and 150,000 square feet of retail and restaurant space.

“The city’s aspirations for this area includes some extraordinary infrastructure that can’t be borne by just one developer or even several,” Richard Suttle, an attorney representing Endeavor, told the Statesman. He did not tell the paper what it meant for the Statesman redevelopment, and did not respond to The Real Deal’s request for comment.

The neighborhood groups that sued to stop the TIRZ, including Save Our Springs Alliance and Taxpayers Against Giveaways, persuaded the judge that the 1981 constitutional amendment that established tax increment reinvestment zones requires the City Council to prove an area is “blighted” and would not develop without the extra money. Given the neighborhood’s high land values, they argued the area includes “some of the most valuable real estate in Austin and likely in all of Texas.”

They also quoted former Mayor Steve Adler, who suggested in a 2022 public hearing that the area would grow regardless of whether it got a TIRZ. “No one is saying that this area wouldn’t develop if we didn’t do this,” Adler said at the time. “It’s just not going to develop the way that we would want it to develop.”

Austin has historically granted fewer tax increment reinvestment zones than Houston and Dallas, but this is one of the largest to be defeated in the city.

“Hopefully the City Council will learn from this and stop spending the public money on corporate welfare boondoggles,” one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys, Fred Lewis, told the Austin Monitor.

Another attorney for the plaintiffs, Bill Aleshire, said told the publication he doubted the legality of some other zones in the state. “It’s about time the restrictions in the tax code were enforced,” he told the Monitor.

“We are disappointed in the ruling,” said Shelley Parks, a spokesperson for the city. “That said, we do not believe this decision impacts the City’s ability to move forward with proposed zoning changes for the South Central Waterfront area.”

Read more