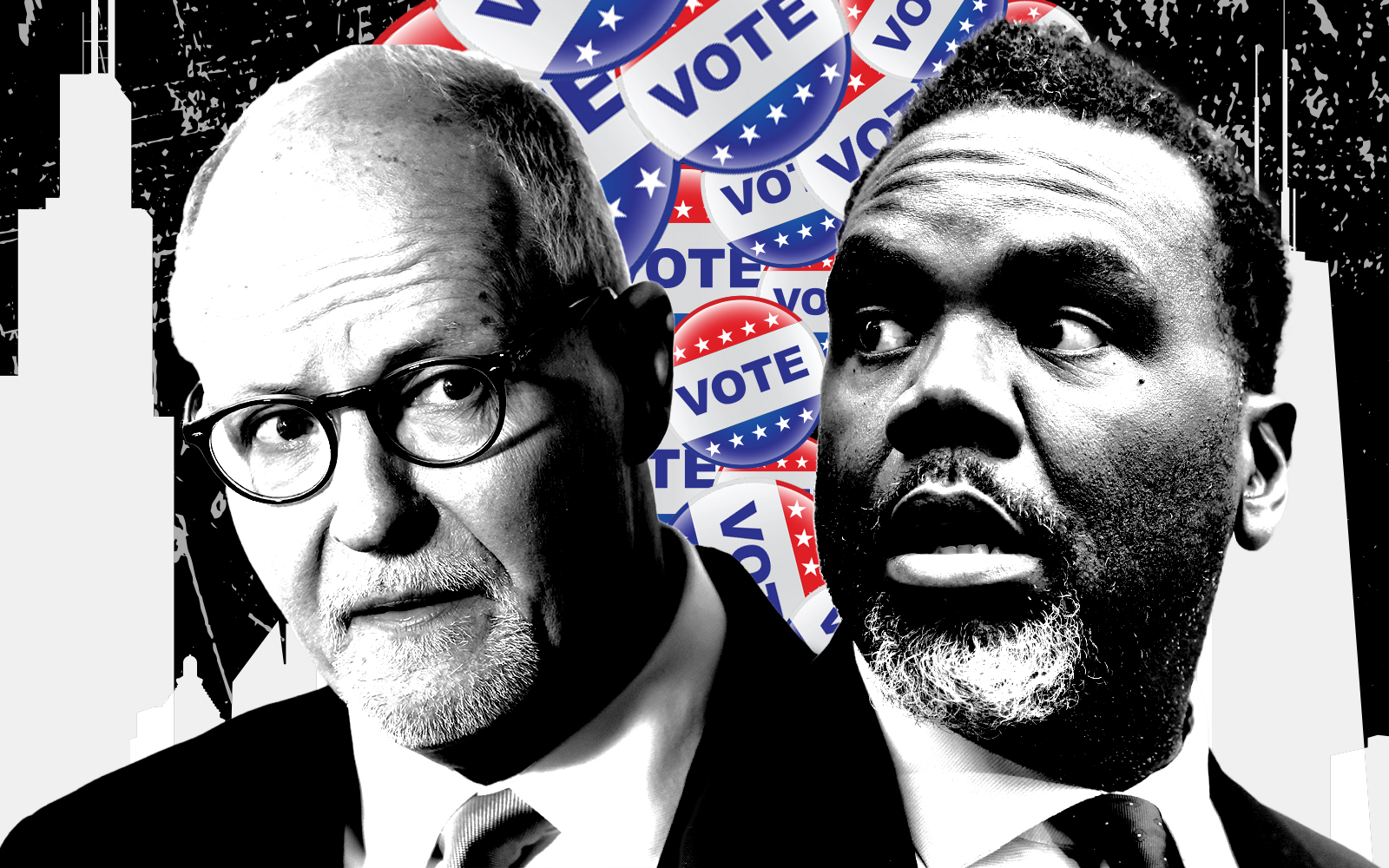

Chicago Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson’s plan to inflate the city’s real estate transfer tax has multifamily industry groups on edge.

The proposal, if passed into law, will almost certainly impact smaller business owners, landlords and, over the long term, renters, according to Michael Chioros of the industry group Neighborhood Building Owners Alliance.

Deal volume data backs up his claim, as multifamily players take closer looks at how hard the sector would be hit by the tax while Johnson transitions into power. They’re finding about a fifth of the new revenue it would generate for public coffers would come from apartment sales, according to analyses of CoStar data by real estate professionals who separately shared their findings with The Real Deal.

In the year-long period leading up to March, about $2.3 billion in multifamily property sales took place in Chicago on deals that totaled more than $1 million. That’s the price point at which the additional transfer tax of 1.9 percent would take place under the Johnson-backed proposal, on top of the 0.75 percent tax already in place.

So roughly 20 percent of the new tax would be derived from multifamily sales, since deals including all asset classes above the price benchmark totaled more than $9 billion in volume in 2022.

Many small multifamily buildings also include retail or office space, which both have been struggling since the pandemic and have already devalued some assets, Chioros said. Additional taxes and rising interest rates will leave less room for owners to take any proceeds from a building sale and reinvest it into additional properties.

“Some people think landlords pocket 100 percent of the rent, the reality is we’re lucky if we get 5 or 6 percent of that at the end of the year,” he said. “It’s the same thing with a sale. It’s not this big pot of gold that someone’s getting.”

The additional tax could lead to more pressure on rents, where its costs may be passed onto renters.

“If someone has to pay a higher price because of the transfer tax, where does it come from? Each additional tax adds more pressure to increase rents,” Chioros said. “Let’s face it, smart landlords really don’t want to increase rents excessively because then you have turnover costs.”

While nicknamed the “mansion tax,” both commercial and residential properties sold for $1 million or more would be impacted. The extra taxes collected would be earmarked to fund services that combat homelessness — and come on top of transfer taxes imposed by Cook County and the state.

“Our biggest concern is that it will impede the transaction of multifamily properties. That will serve as a disincentive to invest in multifamily property along with other rising costs that multifamily property owners have, like rising interest rates, increase labor costs, increase property taxes, utilities,” Chicagoland Apartment Association’s Michael Mini said. “This is just going to be another increase that is going to be difficult to swallow.”

There were about 445 multifamily sales for more than $1 million in the year long period leading up to March, according to one analysis. They involved more than more 13,000 units total, according to the other, and the average sale in that batch included 30 units for $5.3 million total, or $177,000 per unit.

Advocates behind the proposal, a coalition known as Bring Chicago Home, say it would generate an additional $163 million annually, based on the average yearly revenues from transfer taxes from the last 10 years, according to Doug Schenkelberg, executive director of Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, one of the organizations closely tied to Bring Chicago Home.

The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless did not respond to an additional request for comment on potential impacts to the multifamily market.

Bring Chicago Home hasn’t provided a breakdown of the total amount of tax that would be extracted from commercial versus residential sales. But ahead of Johnson’s election victory, The Real Deal’s analysis of deed transfers within from March 1, 2022 through last month found the 50 priciest deals — ranging between $170 million and $18.5 million — involved nearly exclusively commercial properties spanning the multifamily, office and industrial sectors, and would have accounted for about 20 percent of the new tax revenue.

The analysis showed, without carving out exemptions to real estate transfer taxes, the hike would have added roughly $170 million into city coffers during that time period, which is on par with Bring Chicago Home’s estimate.

Mini said the tax could slow down deal volume and lead to stagnation in the multifamily market, while Chioro said the impact is already palpable and some lenders and developers are looking to other markets where the returns are more stable.

“Many small developers — guys building 10, 20 or 30 units — have stopped looking at anything in the city of Chicago and are going to Houston, Dallas, Nashville and Salt Lake City,” Chioros said. “[Outside investors] are not coming here because they can’t predict what the return is going to be if they can’t accurately predict what the real estate taxes are.”

The spelling of Michael Chioros’ surname was corrected in the final paragraph of this story.

Read more