It’s no secret that New York City developers have over the past few years been tapping the EB-5 spigot. Giant builders like Macklowe Properties, Extell Development, the Witkoff Group and the Related Companies have all helped themselves to the relatively cheap capital they can access through the program.

It’s no secret that New York City developers have over the past few years been tapping the EB-5 spigot. Giant builders like Macklowe Properties, Extell Development, the Witkoff Group and the Related Companies have all helped themselves to the relatively cheap capital they can access through the program.

But now, the relative affordability of EB-5 cash compared with traditional financing — the main draw of the program — is being compromised by strong developer demand, increased competition for Chinese investors and a rise in the fees charged by intermediaries, sources told The Real Deal.

In other words, that heavy-handed use of EB-5 is killing the goose that laid the golden (real estate) egg. And if costs keep ballooning at this rate, sources say, developers will begin to scale back their EB-5 usage.

“From the first to the last deal, the pricing has probably doubled,” said Christopher Clayton, an executive vice president at Forest City Enterprises, which has used the program to fund the construction of six buildings since 2010 as part of its massive Pacific Park project in Brooklyn.

“We’ll have to monitor the pricing because at some point it may be easier just to go the traditional route,” he said.

The simultaneous increase in the number of traditional lenders providing subordinate financing for well-located Manhattan developments at competitive rates has also changed the financial calculus for developers.

Matthew Petrula, a senior group manager in the commercial lending group at M&T Bank, said new players have been rushing into the mezzanine lending space because, with rising property values in New York, equity investments have become too expensive. All of that new competition has pushed down the price of mezzanine financing — and narrowed the cost spread between conventional and EB-5 money.

That, he said, may also begin to chisel away at EB-5’s appeal to developers.

“This added competition has driven down the cost of sub-debt borrowing, resulting in a tightening of the pricing gap relative to EB-5,” he said.

If the cost of EB-5 money further skyrockets, sources say it will become a last resort.

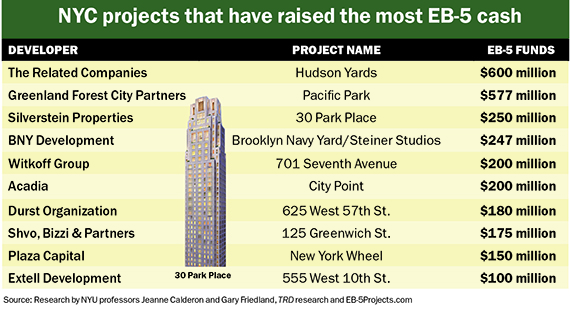

Source: Research by NYC professors Jeanne Calderon and Gary Friedland, TRD Research and EB-5Projects.com

“If developers are willing to overpay for access to this money, they must not have been able to get money from another source,” said Mike Xenick, president and CEO of Invest America Capital Advisors, a Tampa-based EB-5 broker dealer. “You start to think about how desperate they are and why.”

A new reality

New York developers who hopped on the EB-5 train early — in the years immediately following the 2008 market crash — said the current landscape looks remarkably different than it did back then. Where they were once pioneers peddling the American dream to hungry foreign investors, they are now competing with dozens of other developers in the city with similar projects.

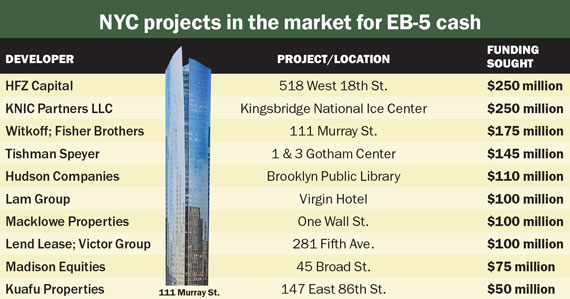

“In New York alone, there are easily more than 100 projects looking for EB-5,” said Michael Gibson, managing director at the Miami-based USAdvisors.org, an investment-advisory firm that specializes in EB-5. “If you look at just the top 10 projects, those alone surpass the amount of available EB-5 capital. Ninety percent of these deals aren’t going to get funded.”

This new level of competition to woo EB-5 investors not only lengthens the time it takes for a developer to market and close a deal, but it also drives up that developer’s costs.

Indeed, five to 10 years ago, developers were able to secure EB-5 money with interest rates of around 3 to 4 percent — a steal for mezzanine debt. Now that number is close to 7 percent. That’s still a significant discount when compared to the 10 percent interest often charged by traditional banks, but the differential is quickly shrinking.

“It’s not easy to raise this money,” said Forest City’s Clayton. “It’s a lot of people on the ground. There’s an effort and a time commitment to the process that’s longer than you’d face in traditional financing. And the longer a transaction takes, the more risk there is … particularly in a volatile global market.”

For developers who are new to the EB-5 game, it’s especially tough to compete with big players such as Related and Extell, who have more negotiating power and a track record with Chinese capital.

Some say those high-profile developers are hogging the limited amount of EB-5 money. (EB-5 capital pouring out of China, which accounts for the vast majority of the program’s cash, amounts to a total of around $2 billion a year.)

“They’re sucking all the air out of the room,” Gibson said. “These little guys put in so much effort, spend a lot of money, only to realize no one is interested. They need 300 or 500 investors and go home with 20 or 40.”

Compounding matters is that the attorneys and other consultants who make their livelihoods off of these deals have no incentive to warn developers of the intense competition. There’s too much money on the line for them.

And developers who are new to EB-5 may also struggle to compete with projects that have buy-ins from big Chinese firms, such as Pacific Park, where Chinese conglomerate Greenland owns a 70 percent stake, and at developer Michael Shvo’s 275-unit condo 125 Greenwich, where Chinese investment firm Cindat Capital Management is an equity partner.

“The Chinese are going to go with the Chinese, not because they trust them but because at least they know how to get a hold of them,” Gibson said. “It’s Chinese capital going directly to the Chinese.”

Cutting costs

The tightening spread between EB-5 and traditional mezzanine debt might explain why a significant number of New York developers are trying to cut as many middlemen out of their EB-5 transactions as possible. Those intermediaries include federally designated regional centers — which have sprouted up in recent years and act as clearinghouses for EB-5 capital — and the local Chinese and other foreign consultants, known as migration agents, who steer prospective investors to projects. (See related stories on pages 52 and 58.)

Hudson Yards

Rather than hiring an existing regional center to originate debt on their behalf, developers such as Silverstein Properties and Extell have in the last few years established their own centers, a move that some sources say substantially reduces their costs.

Silverstein established its regional center in 2013 to raise $250 million for 30 Park Place, the nearly $1 billion residential and hotel tower near the World Trade Center.

Meanwhile, Related opened its regional center to secure more than $600 million in financing for Hudson Yards, its massive mixed-use mega-project on Manhattan’s Far West Side. The cost of establishing a regional center typically ranges from between $100,000 and $200,000, irrespective of the size of the project it’s fundraising for.

Some developers have even established regional centers on a speculative basis to prepare for a capital raise when the right project comes along.

“It’s all about options,” said Izak Senbahar of the Alexico Group, who owns two regional centers he’s never even used.

“You never know when you’re going to get a nice piece of land,” he said. “There are a lot of moving parts to a deal and if you’re not ready with the money and you don’t have that regional center waiting, then you won’t have the option to use EB-5 unless you go rely on someone else.”

By bypassing the third-party regional centers as a middleman, developers can set more favorable terms with investors and avoid paying management fees, which typically account for at least 1 to 2 percent of the total financing raised. For a project raising $75 million in EB-5 capital, for example, that amounts to $750,000 to $1.5 million.

Reputational risk

For some developers, the thought of operating a regional center is too daunting; the SEC is clamping down on EB-5 corruption, and there is the potential for negative headlines or even legal liability.

The reputational risk of getting flagged for misusing EB-5 funds — or for using them at all given how much of a lightning rod EB-5 has become — is a big consideration.

“We thought long and hard about becoming our own regional center,” said developer Steve Witkoff, who used a third-party regional center to raise $175 million for his condo project at 111 Murray Street in Tribeca. “We struggled with the securities liability portion of it. You’re under a legal obligation as a fiduciary to report correctly, and it just brings in another layer of liability. It’s one thing to make a mistake from the real estate side; it’s another thing to make a mistake as the entity making a securities offering.”

Regional center operators, who court developers as clients, argue that hiring a third party saves developers both time and money. A center’s existing network of migration agents can effectively market a project in China, operators say, and a developer won’t suffer the headaches that come with interfacing with individual investors and their attorneys.

“We charge 6 to 7 percent on a loan, depending on the strength of the developer,” said Jacqueline Finkelstein-LeBow, a principal at New York-based regional center American Immigration Group. “Some developers will tell you that they can go into the market themselves and get it at 3 percent. That’s complete baloney. It’s just impossible because the migration agents just take too much of that.”

Finkelstein-LeBow added that many builders have learned that lesson the hard way. “They think they can do it themselves and then they realize how tedious the process is,” she told TRD. “It’s being able to have the trust and respect of these agents. If you’re just walking in for the first time, they’re not going to take you so seriously. It’s not easy to get in the door.”

A matter of trust

While developers may not be getting EB-5 cash at as the same bargain-basement price as they did a few years ago, the program is still worth it for many of them — at least for now.

One reason is that EB-5 capital is “remarkably flexible,” meaning it can be debt or equity, secured or unsecured, and can account for as little as 1 percent of a project’s cost or as much as 100 percent, according to a research paper by New York University professors Jeanne Calderon and Gary Friedland. “It can contain virtually any features, with few limitations or restrictions imposed by the EB-5 program,” the duo wrote.

Source: TRD research

It’s especially appealing to developers of large-scale projects. That’s partly because it provides capital for early infrastructure improvements — like environmental land remediation or initial foundation work.

It can be tough for projects to find financing for these early capital outlays, which often take place months, or even years, before the project generates its first cash flow. Private debt providers are generally “unwilling to provide this funding,” Calderon and Friedlander wrote. “Those who are willing demand a substantial premium.”

But there are still significant challenges to those who go the EB-5 route. Two of the biggest are the lengthening wait list for EB-5 immigration petitions and the possibility of more skepticism among senior lenders whose confidence has been increasingly eroded by negative publicity stemming from critics who have described the program as a cash-for-visas scheme.

The difficulty in finding financing is even greater in the rare instances where EB-5 is used as equity rather than debt. M&T’s Petrula said tapping EB-5 for equity is essentially going into business with hundreds of strangers, not something lenders are generally comfortable with. “[It] adds a level of complexity and uncertainty to a capital stack that many senior lenders choose to avoid,” he said.

Senior lenders are, not surprisingly, more accepting of partners with solid track records — not to mention those who they can meet and vet in person. That’s because they need confidence that their partner will step up to pour more money into a project if a deal sours. “[They have the] wherewithal to fund capital calls and protect in a bad situation,” Petrula added.

But the long processing times for EB-5 investors’ applications may be an even bigger problem for developers because it can delay their access to capital.

“The biggest risk to demand for the program is if waiting times for Chinese nationals grow further,” said Justin Gardinier, the former managing director of the recently launched EB-5 group at the financial services firm Greystone.

There’s also the risk of litigation should a project go south and investors lose their money. If investors can prove they were misled, developers could have a wave of lawsuits on their hands. “You put a 90-year-old Chinese grandma who lost all her money on the stand and it’s going to cost them millions of dollars,” Gibson said.