President Trump’s federal budget, released Monday, proposes to slash $3.6 trillion in government spending over 10 years. It vows to spend money “only on our highest national priorities, and always in the most efficient, effective manner.” And yet, like so many prior budgets, it doesn’t touch one of the country’s most wasteful and perverse subsidies: the mortgage interest deduction.

In a recent New York Times magazine article, Matthew Desmond explains why the policy, which allows homeowners to deduct mortgage payments from their taxes, is misguided. The deduction is regressive. It disproportionately benefits wealthy homeowners with big mortgages. Poor people, who tend to rent, often get far less support.

But Desmond’s piece only scratches the surface of why the MID (and similar homeownership subsidy schemes like federally-backed mortgage insurance) are a bad idea. It doesn’t just benefit rich people, it benefits rich people at the expense of the poor by driving up their rents. It is, quite literally, a wealth transfer program that takes money out of the pockets of the neediest and gives it to wealthy property owners.

To understand why, here’s a brief explainer on how MID and federally-backed mortgage insurance drive up property prices, and how that, in turn, drives up rents for the urban poor.

According to a well known 1996 study by Richard Green, Patric Hendershott and Dennis Capozza, U.S. home prices may be between 13 and 17 percent higher than they normally would be because of the MID. The logic is simple. The deduction makes it cheaper for Americans to take out mortgages, which means they can afford to pay more for homes, which artificially inflates demand, which in turn drives up home prices. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the federally backed mortgage giants, have a similar impact because they, too, drive down the cost of borrowing for millions of Americans and inflate demand.

“When we think of entitlement programs, Social Security and Medicare immediately come to mind,” Desmond writes. “But by any fair standard, the holy trinity of United States social policy should also include the mortgage-interest deduction — an enormous benefit that has also become politically untouchable.”

The MID and mortgage insurance aren’t the main reason urban home prices rose in recent years — the credit goes to demographic trends, foreign investment and economic growth. But it’s safe to say they play a role.

In a perfect market, developers would respond to high home prices by building more, which would eventually push prices down again. But in practice it doesn’t work that way — at least in cities. Urban land is scarce and expensive and zoning often limits building heights. This means developers can only do so much to respond to rising demand. A new study by construction services company BuildZoom blames this for rising home prices in the U.S.

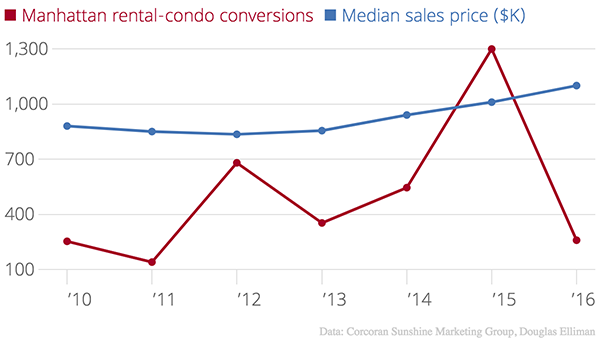

Rather than build, developers often pick a more convenient way to cash in on rising prices: they convert rental units into condos or for-sale homes. New York is a prime example. Between 2013 and 2015, the median Manhattan apartment sales price rose by 18 percent, according to brokerage Douglas Elliman. During the same period the number of rental apartments converted to condos more than tripled from 355 to 1,299, according to Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group. When new developments are built in Manhattan, they normally go the condo route.

As conversions picked up, the supply of for-rent apartments stagnated even as more and more people moved to Manhattan. So rents rose. Private equity giant Blackstone Group was one of the firms that spotted this trend and bought up thousands of Manhattan rental units. “When you have virtually no new supply of rentals net of condo conversions, that’s part of why we expect to see continued cash-flow growth,” Blackstone’s Nadeem Meghji said last year. “We think rental supply has been modest and will remain reasonably modest.”

As condo conversions and a lack of new rental construction push up rents in Manhattan, more middle class New Yorkers are forced to move into cheaper neighborhoods, where they displace long-term residents, who in turn move into even cheaper neighborhoods, displacing yet other locals. And so, connected through these ripple effects of gentrification, condo prices in Manhattan and apartment rents in the Bronx move in the same direction: up (see chart).

As condo conversions and a lack of new rental construction push up rents in Manhattan, more middle class New Yorkers are forced to move into cheaper neighborhoods, where they displace long-term residents, who in turn move into even cheaper neighborhoods, displacing yet other locals. And so, connected through these ripple effects of gentrification, condo prices in Manhattan and apartment rents in the Bronx move in the same direction: up (see chart).

Like New York, most U.S. metropolitan areas have seen rising for-sale home prices go hand in hand with rising rents. And if higher home prices correlate with rising rents, the reverse is also true. If for-sale home prices were to fall substantially, developers would have an incentive to convert them to rentals (which is exactly what happened after the subprime mortgage crisis). That would increase supply and keep a lid on rents.

What does this mean in practice? Let’s pretend home prices in U.S. cities are on average 15 percent higher because of mortgage interest deduction and mortgage insurance (the real number could be much lower or it could be higher). It’s not far-fetched to argue that as a result rents are also inflated in markets where land is scarce. A 2004 Federal Reserve Board study by Joshua Gallin found that when home prices are high relative to rents, rent increases over the following three years tend to be larger than usual. Renters, who are disproportionately low-income, suffer. They pay more in rent and are left with less disposable income. They are poorer thanks to MID and mortgage insurance. Urban homeowners, in contrast, are 15 percent richer. One wins because the other loses. It’s a disguised wealth transfer.

Despite all of that, politicians consider the MID untouchable. When HUD secretary Ben Carson floated the idea of ditching the MID last year while running in the presidential primaries, Republican strategist Bradley Blakeman called him “the Kevorkian of taxes.” Homeowners are well aware how much they benefit from the program and would punish any elected official brave enough to scrap it. Renters, in contrast, never threw their weight against it — perhaps because the way they lose out from the MID is so opaque and perhaps because most hope to become homeowners themselves one day. But they should. Homeownership subsidies like the mortgage interest deduction, and to a lesser extent federal backing of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are engines of inequality. Getting rid of them wouldn’t solve the affordability crisis in U.S. cities, but it would be a step in the right direction. And it could save Trump’s budget $134 billion, which is what homeownership subsidies cost in 2015, according to the Times. Not a bad deal.