At the onset of the pandemic in March, few anticipated that Manhattan offices would remain mostly unoccupied deep into the fall.

New data show just how bad: At this pace, leasing volume in 2020 will be 52 percent lower than the year before, according to Franklin Wallach, Colliers International’s senior managing director for New York research.

That compares to a 26.9 percent plunge from 2007 to 2009 and a 14.1 percent decline after the 2001 crash, the report noted.

“The scale of the decrease in demand is on track to double the scale of decrease during the Great Recession,” Wallach said.

Read more

The dramatic falloff this year was attributable to horrific second and third quarters that have cost some of the city’s top commercial real estate brokers their jobs. Layoffs have rocked JLL, CBRE, Avison Young, B6 Real Estate Advisors, Marcus & Millichap and others.

However, office availability spiked much more in the prior downturns. The rate went up by 42 percent in the six-month period following the 2001 crash, and by 52 percent in the third and fourth quarters of 2008. From April through September this year, availability went up by about 20 percent.

The 3.12 million square feet of sublease space that came on the market from April to September boosted sublets’ share of total availability up only slightly, to 23.2 percent from 22.1 percent. The sublet share gain was much bigger in 2001, when it went from 6.8 percent to 25.9 percent in the six months following the dot-com crash.

A decline in Manhattan’s asking rent average was relatively small in the second and third quarters this year — 3 percent — partly because landlords took a “wait and see” approach during the second-quarter lockdown, Wallach said. In the third and fourth quarters of 2008, the average asking price dropped by 15.3 percent.

Although the current downturn has largely been marked by a lack of leasing, downward pressure on pricing could still intensify if more businesses downsize.

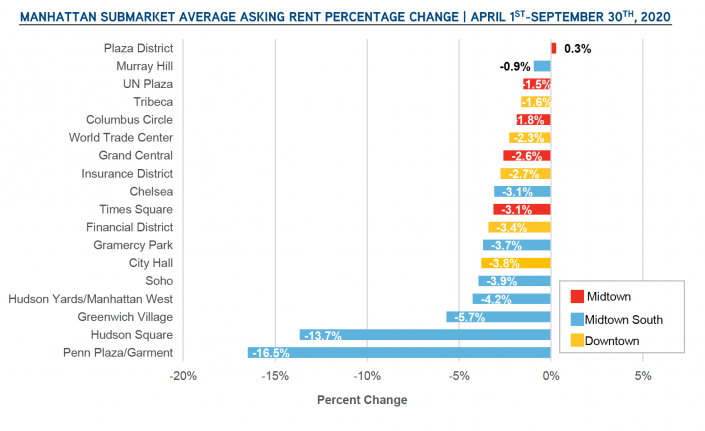

Among Manhattan’s 18 submarkets, the Plaza District’s average asking rent was mostly unchanged from April to September, but the other 17 submarkets experienced declines. (See chart.)

A 16.5 percent drop in the Penn Plaza/Garment district was mostly caused by the removal of the high-priced space at the Farley Post Office development leased to Facebook in August. The 13.7 percent dip in Hudson Square was primarily driven by low-priced sublet space listed at 1 Hudson Square, according to the report.

One of the reasons for a steeper price decline in Midtown South was because the area was booming — and the price was rising — before the pandemic, creating room for the price to come down. But the Midtown market, whose older inventory was losing tenants even before the pandemic, didn’t have as much to lose from asking prices, Wallach said.

But Midtown also has new construction, such as One Vanderbilt and 390 Madison Avenue, along with 1271 Avenue of Americas, which is undergoing a major renovation.

“There is still plenty of demand in the Midtown market, especially for the newer products,” Wallach said.